Scientist of the Day - John Frere

Linda Hall Library

John Frere, an English antiquarian, was born Aug. 10, 1740. In 1797, Frere discovered the stone age. He visited a brick quarry a little south of the village of Hoxne, in Suffolk. There he found a number of flaked flint objects buried deep in the earth, about 12 feet down, and since the flints resembled axe heads, he surmised that these were human artifacts. In his words, the tools were “weapons of war, made by a people who had not the use of metals.” Moreover, because the tools were found under a layer of sand containing shells, he reasoned that they must have been deposited at a time before water covered the covered the land in that area--a time that was nowhere mentioned in written history. Frere concluded that these tools were prehistoric. Supporting this conclusion was the large jawbone of an unknown animal, itself seemingly prehistoric, that was found among the tools.

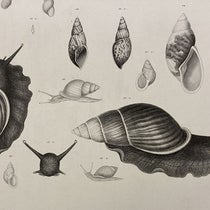

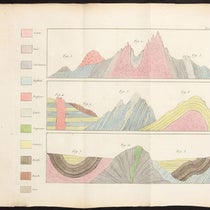

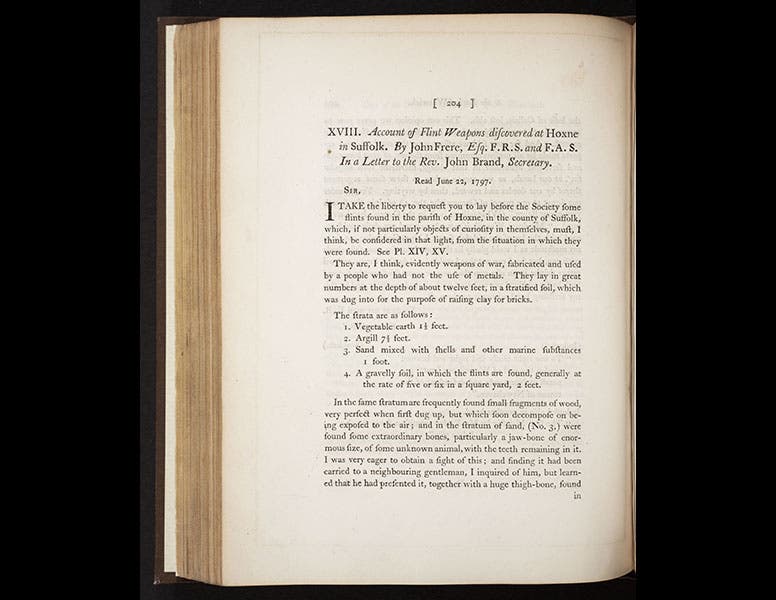

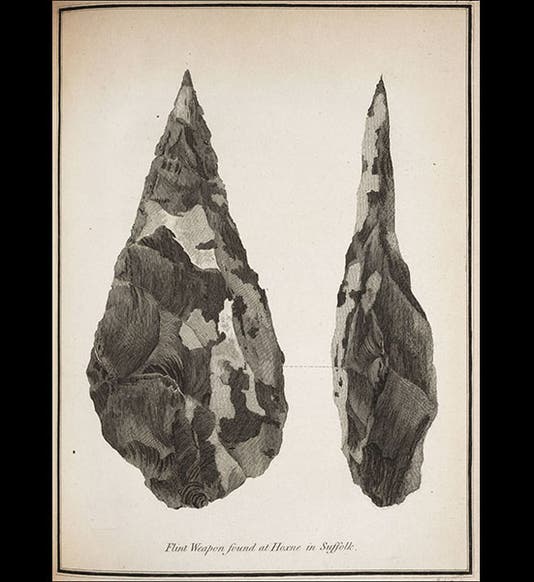

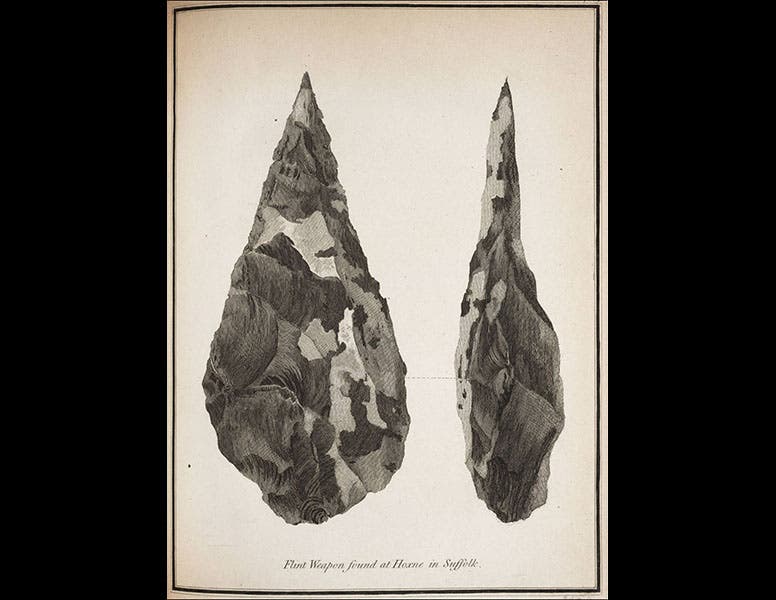

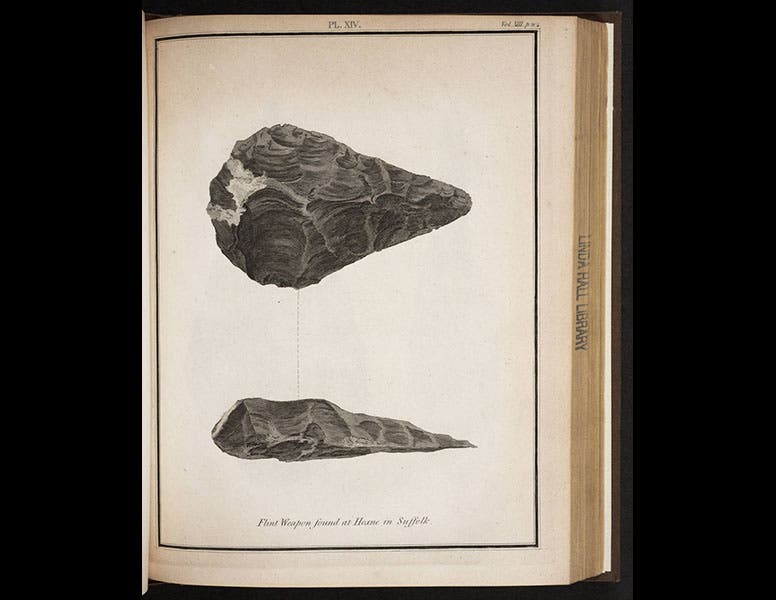

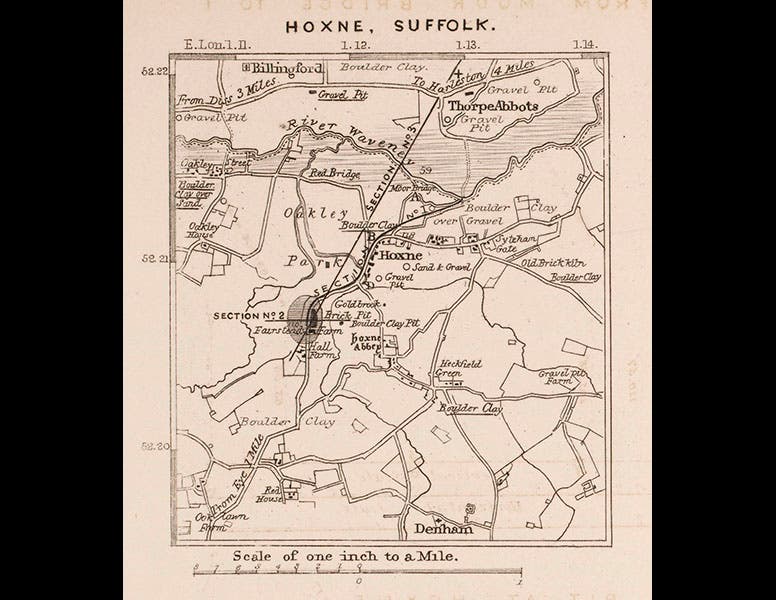

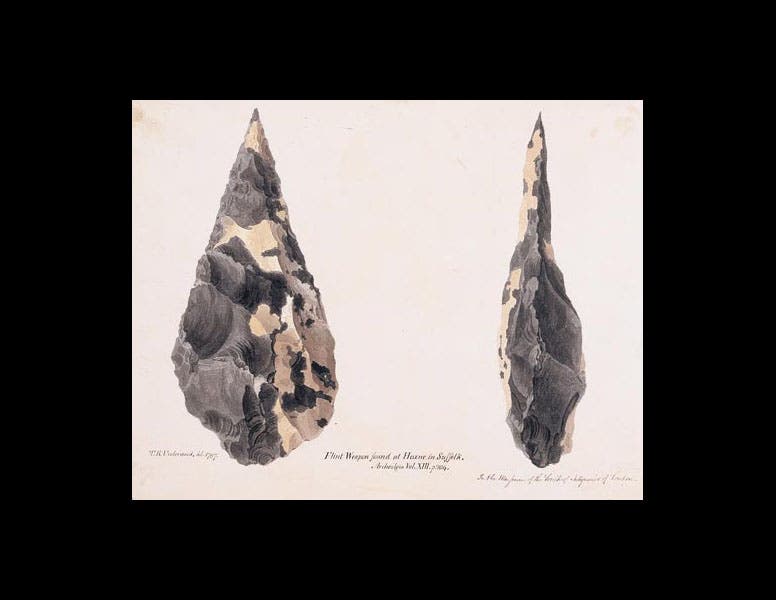

Frere discussed his finds and conclusions and published etchings of several of the flints in 1800 in Archaeologia, the journal of the Society of Antiquaries of London (first three images). But no one seems to have paid any attention to Frere's discovery or its import for another 60 years, even though the Hoxne tools were in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries, and at least one made it into the British Museum and was there for all to see. In 1859, when Joseph Prestwich had just returned from Amiens, France, having discovered a prehistoric hand axe in situ, his attention was called to the Hoxne flints by John Evans. The Hoxne handaxes were of a kind with the Amiens flint and with artifacts that had been collected earlier in Abbeville by Jacques Boucher de Perthes. Prestwich immediately visited Hoxne and located the brick quarry, and even found an old quarryman who had been alive in 1800 and who remembered the former abundance of the flints found by Frere. Prestwich returned home and wrote his seminal paper, "On the occurrence of flint-implements, associated with the remains of animals of extinct species in beds of a late geological period, in France at Amiens and Abbeville, and in England at Hoxne." It was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1860 and marked a turning point in the acceptance of the idea of human antiquity. It also includes a small inset map of Hoxne and the brick quarry (fourth image). We featured the papers of both Frere and Prestwich in our exhibition of 2012, Blade and Bone: The Discovery of Human Antiquity.

One of the flints found by Frere is still on display in the British Museum (fifth image; it is the hand axe on the right). A watercolor drawing of a Hoxne flint, made in 1797 by Thomas Underwood and used for one of Frere’s plates in his 1800 paper, is in the library of the Society of Antiquaries in London (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)