Scientist of the Day - John Woodward

John Woodward, an English geologist and fossil collector, was born May 1, 1665. Woodward was an early believer in the organic origin of fossils (first proposed by Steno and Hooke around 1668), but he was initially at a loss to explain how fossils became embedded in the earth's crust, if they were the remains of living animals on the surface. And then he got his Big Idea. What if, during the Great Flood of Noah, God had miraculously suspended gravity (by which Woodward meant not Newtonian gravity, but the force of cohesion that holds things together)? As the earth's rocks dissolved into thick pudding, all the drowned animals and planets would sink down until their density was equaled by that of the surrounding muck. When gravity returned, the rocks would cohere again, with the animals remains now imprisoned as fossils within. It was actually a clever idea, except for the density part, which would suggest that the top layers of rock should contain all the jellyfish and the bottom layers all the turtles.

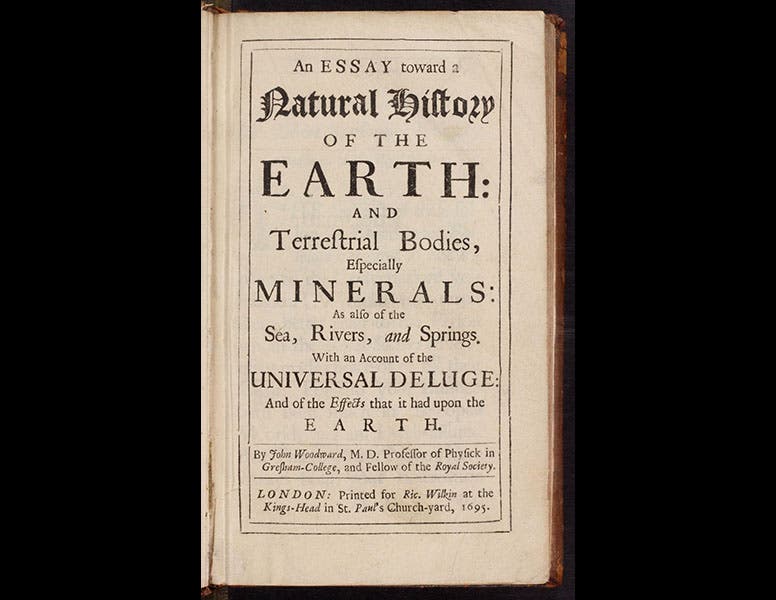

Woodward announced his hypothesis in An Essay toward a Natural History of the Earth (1695; third image), which took its place as an early offering in a long-running genre known as "Theories of the Earth." We displayed quite a number of these, including Woodward's book, in an early Library exhibition, Theories of the Earth, 1644-1830, back in 1984. We have not only the first edition but 7 other early editions of Woodward’s treatise in our History of Science Collection.

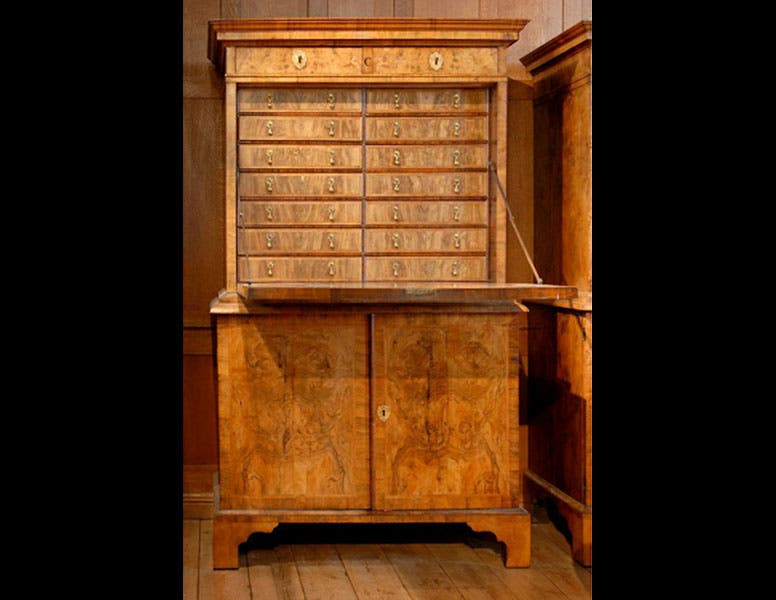

When Woodward died, he left funds to establish a “Professorship of Fossils” at Cambridge University. Although now called the Woodwardian Professor of Geology, the chair is still with us. Adam Sedgwick, the discoverer of the Cambrian system, sat in it for over 55 years, from 1818 to 1873. Woodward’s fossil collection, also bequeathed to Cambridge, is now in the university’s Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences. Because of the carefully-thought-out provisions of Woodward’s original bequest, the collection is still intact—in fact, it is still shelved in the 5 original cases that Woodward himself had commissioned. We see above one of the cases (fourth image), and one of the drawers (first image), this one housing various glossopetrae, or sharks’ teeth.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.