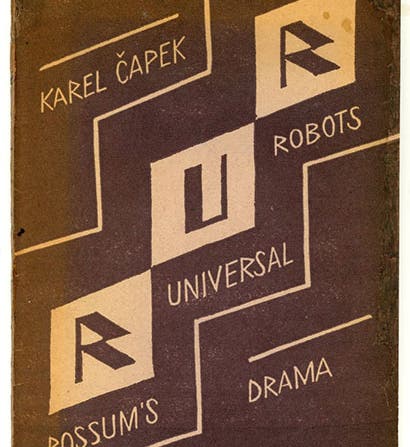

Scientist of the Day - Karel Čapek

Karel Čapek, a Czech author and playwright, was born Jan. 9. 1890. We featured Čapek in this space four years ago, where we discussed his 1936 science fiction novel, War with the Newts. But Čapek is better known for his play that debuted in 1921: R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), which will provide our focus today (first image). Most people know that the word "robot" that appears in the play's subtitle marks the introduction of the term into human discourse. The play itself is not so well known, since it is seldom performed today, although it was quite the rage on Broadway in 1922/23. I decided to re-read it for the occasion, and the following are my thoughts on Čapek's robots. The plot is fairly simple. On an island somewhere, a factory founded by a now-deceased inventor named Rossum churns out hundreds of thousands of robots. These are not mechanical humans but rather organic creations, produced by a technique developed by old Rossum, using a secret recipe that is closely guarded. A woman arrives, Helena, the daughter of a "president" who is not otherwise identified, and who has the secret agenda of liberating the robots and giving them human rights (second image).

Helena is very attractive and all the humans on the island (there are not many) are drawn to her. She ends up marrying the head manager, and ten years pass. During that interval, one of the engineers, prodded by Helena, has begun making robots that are more "human" in some unspecified way. These humanized robots resent the humans who dominate them, and they lead a revolt. Eventually all humans worldwide are exterminated, except for one engineer, Alquist, who is given the task of discovering how to produce more robots, since they have a 20-year life span. But Helena, before her own death, has burned old Rossum's recipe. Alquist fails at his task, so most of the robots are doomed to suffer the same fate as the humans, but two of the modified robots, Primus and Helena, fall in love at the very end, suggesting that one day the Earth might see the rise of a new kind of civilization. The play is dated in many ways but surprisingly fresh in others. The idea that even "soulless" robots might resent human mistreatment and rebel against their oppressors is at the heart of the film I, Robot (2004) (but not the Isaac Asimov book of that title), and the notion that robots would (and should) have a limited lifespan is a central element in Blade Runner (1982). Certainly the idea that humans find purpose and meaning in work and might cease to reproduce if all work is done by robots (as happens in the play) is thought provoking even today.

Karel on several occasions took the trouble to point out that while the word "robot" first appeared in print in R.U.R., the word was in fact coined by his brother Josef, from robota, the Czech word for drudgery. Josef was a prominent Czech painter and writer, as well known at the time as Karel. The two are quite the pride of Malé Svatonovice in the Czech Republic, where there is a museum in their honor and a prominent statue of both of them in the village square (third image). Karel is at the left, holding a watering can, probably a reference to one of his most enduringly popular works, The Gardener’s Year (1929). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.