Scientist of the Day - Nehemiah Grew

Nehemiah Grew, an English botanist and microscopist, was baptized Sep. 26, 1641; his date of birth was not recorded. Grew was a pioneer in plant anatomy in the 1670s, wielding the new compound microscope to great effect in unraveling the vascular systems of plants, but we speak today of Grew's role in publishing the first catalogue of the Royal Society's "Repository," as they liked to call their museum of natural objects. The Repository was founded in 1663, a year after the Society itself received its charter, as various people gave gifts of odd objects to the Society. “Cabinets of Curiosities” had long been flourishing in late 16th- and 17th-century Europe; you could find them in the domiciles of wealthy citizens or the castles of emperors, and in at least one case, in the home of a bona fide natural philosopher, Ole Worm of Copenhagen. No scientific institutions had museums until the Royal Society established their Repository, which is not surprising, since there were very few scientific societies before the Royal Society came into existence.

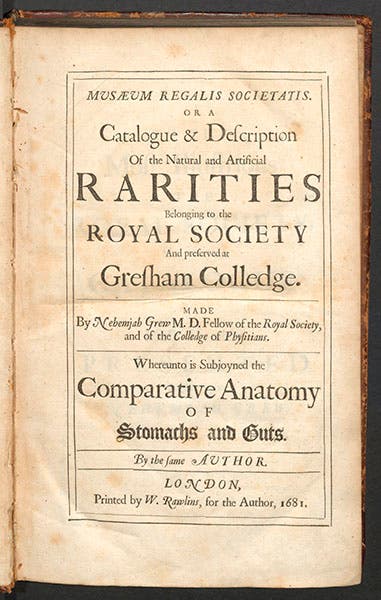

Title page, Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum regalis societatis, 1681 (Linda Hall Library)

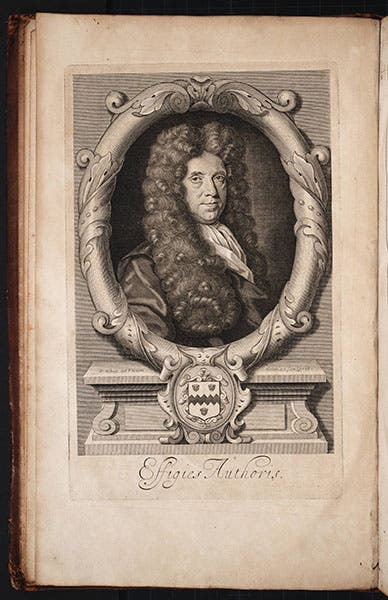

Cabinets of curiosities tended to give precedence to exotic or bizarre objects, so in no instance were they museums of natural history, nor were they intended to be such. The visitor to the cabinet was to be amazed and amused, not educated or motivated to classify the animal or plant kingdoms. The Royal Society Repository started off the same way, when they acquired the cabinet of Robert Hubert (sometimes referred to as Hubbard), a wealthy English collector, for £100 in 1666. The man who arranged the purchase was the Society’s treasurer, Daniel Colwall. For years the collection was kept in the rooms of the curator of experiments, Robert Hooke, added to here and there by donations, but eventually it found its way into a wing of Gresham College, where the Society held their weekly meetings. Grew took over as Secretary of the Society after the death of Henry Oldenburg in 1677, and he was soon given the task of publishing a catalogue of the items in the Repository. He did so in a very short span of time, which suggests that Hooke and others had prepared preliminary catalogues that Grew was able to use. In 1681, the catalogue was published, as Musaeum regalis societatis: or A catalogue & discription of the natural and artificial rarities belonging to the Royal Society and preserved at Gresham Colledge, which we have in our collections (second image). The frontispiece portrait is not that of Grew or Hubert, but of Colwall; apparently the Society now realized what a bargain the £100 acquisition of the Hubert collection had been.

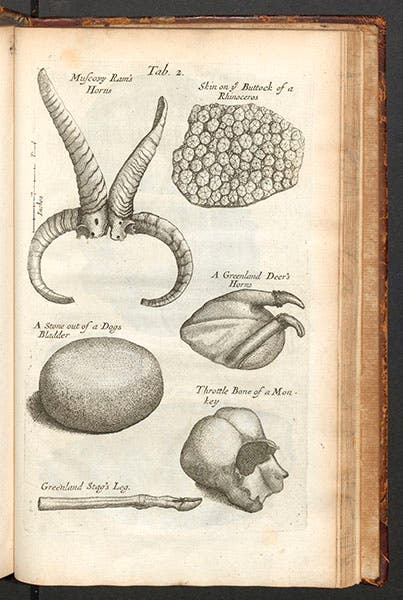

Muscovy ram’s horns, skin of a rhinoceros buttock, horns and leg of a Greenland deer, engraved plate, from Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum regalis societatis, 1681 (Linda Hall Library)

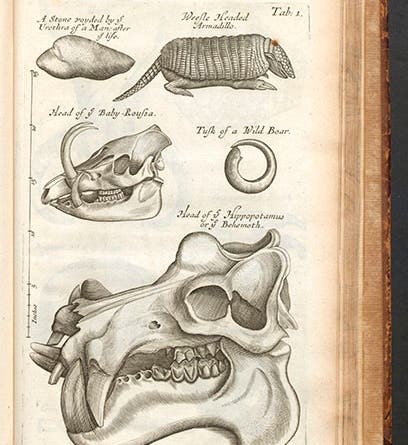

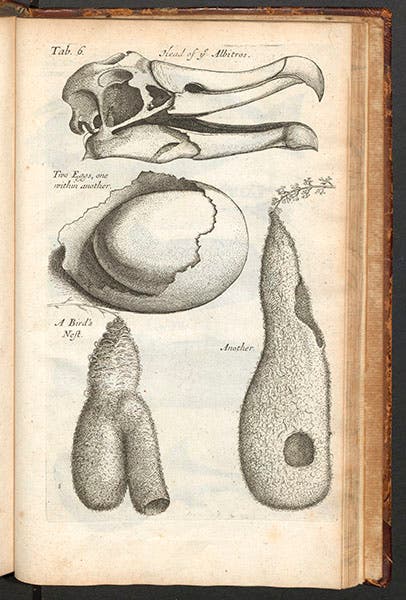

Grew's catalogue of the Repository is important because it marks a sharp break in the tradition of collecting. The natural, rather than the preternatural, now took precedence. Grew's real intent was to order the natural world, not display its idiosyncrasies, and he saw a museum as a useful aid for the task of classifying nature. For illustrations he chose, he said, objects that had not been previously illustrated, so the images tend to be more exotic than representive, but still, you would probably not find the skin of a rhino’s buttock or a collection of birds’ nests in a traditional cabinet of curiosities.

Albatross skull, bird’s nests, engraved plate, from Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum regalis societatis, 1681 (Linda Hall Library)

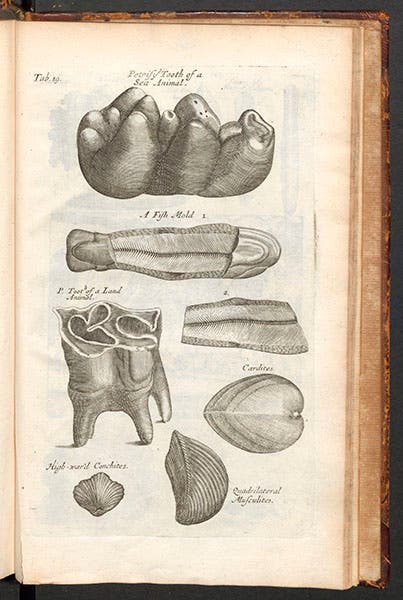

Mastodon tooth, fossil fish and shells, brachiopod, engraved plate, from Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum regalis societatis, 1681 (Linda Hall Library)

The most telling difference is that Grew’s catalogue has no introductory plate depicting the traditional "wonder room" – a place where the visitor would be bedazzled by birds of paradise and crocodiles and pearly nautili. In fact, there is no picture of the physical Repository at all. The cabinet of curiosities has evolved into the natural history museum, thanks to the new vision of Nehemiah Grew and his colleagues.

Portrait of an older Nehemiah Grew, engraving, from his Cosmologia sacra, 1701 (Linda Hall Library)

We have no portrait of the Grew who organized the Repository; the only portrait we have was engraved 20 years later, when Grew was more interested in natural theology than taxonomy (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.