Scientist of the Day - Scipione Breislak

Scipione Breislak, an Italian geologist, was born Aug. 17, 1748. Breislak began his career in Rome, spent some time in Naples, and finished out in Milan, so he saw a great deal of the varied geology of Italy. He was an early convert to vulcanism – the idea that much of the earth's surface rock, including all of its basalt, had emerged from volcanoes and cooled from a molten state. He even had the idea that Rome was built on an ancient volcano, and that the present-day seven hills of Rome are remnants of the old lip of the volcano (this turns out to be ingenious, but wrong – most of the volcanic rocks in Rome come from a volcano a moderate distance away).

Breislak's fascination with basalt led him to publish a geological atlas in 1818 that contained 53 views of basalt formations, from the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland to Fingal's Cave in the Scottish Hebrides to the Vivarais in France to the Euganean hills in the Veneto of Italy. Not surprisingly, we displayed this atlas in our 2004 exhibition, Vulcan's Forge and Fingal's Cave. But it was frustrating to be unable to exhibit more than one plate, for they are all quite striking. The plate we displayed shows a castle in Stolpen, Gemany, that was built upon a layer of columnar basalt. This was one of the few basalt formations known to Abraham Werner, the great German systematist, who concluded from its seemingly stratified appearance that basalt was NOT Igneous in origin, but formed from water like all other sedimentary rocks. As it turned out, Werner was wrong, and Breislak was right. Here is a detail of the basalt columns in the Stolpen scene.

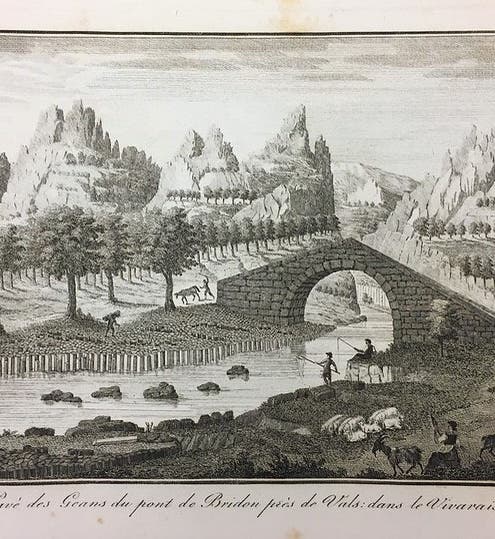

For this occasion, we show and link to several other plates in the Atlas geologique. Our first image is a plate showing a site in the Vivarais region of southeastern France, where a stream cuts through a bed of columnar basalt, with a bridge built over the stream. Our second image is a detail of a plate depicting the basalt prisms of Santa María Regla in Hidalgo, Mexico, which was observed by Alexander von Humboldt (in fact, the entire plate is borrowed from Humboldt). In addition, we link to the engraved title page of the Atlas, which shows structural details of columnar basalt; a detail showing the isle of Staffa, the site of Fingal’s cave; and a detail of the plate that shows basalt columns near Mt. Vesuvius.

Interestingly, although he was a staunch vulcanist, Breislak resisted plutonism – James Hutton’s proposal that other kinds of rocks, most notably granite, had cooled from a molten state under the earth’s surface. Breislak believed that plutonism depended on the existence of a sizable amount of subterranean heat, which had yet to be demonstrated.

We have 5 other works by Breislak in our History of Science Collection, including one with a beautiful colored geological map of the area around Naples and Mt. Vesuvius, which we also exhibited in Vulcan’s Forge. The online catalog shows a detail, but the entire folding map is much more impressive, and like most large maps, has to be seen in person to be appreciated.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.