Scientist of the Day - Alberto Fortis

Alberto Fortis, an Italian geologist, was born on Nov. 9 or 11, 1741. Fortis came out of the Paduan scientific tradition that began with Galileo Galilei and was carried on by followers, including the geologist Antonio Vallisneri, who taught at Padua until his sudden death in 1730, before Fortis was born. Fortis absorbed the Paduan scientific ethos in the 1750s, when the chair of natural history was held by Vallisneri's son, Antonio, Jr. But Fortis was most influenced by a non-academic mining engineer, Giovanni Arduino, who wrote a letter to Antonio, Jr., in 1759 in which he laid out an entire geological program for understanding the rock formations of the Veneto, as the region between Venice and the Alps was called. Arduino pointed out the abundance of volcanic material in the Venetian hills and called for detailed mapping and study of the rocks. Fortis was happy to oblige.

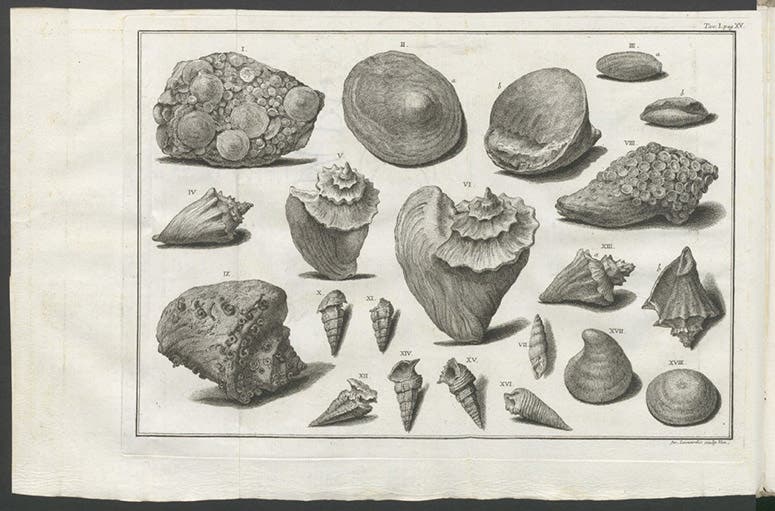

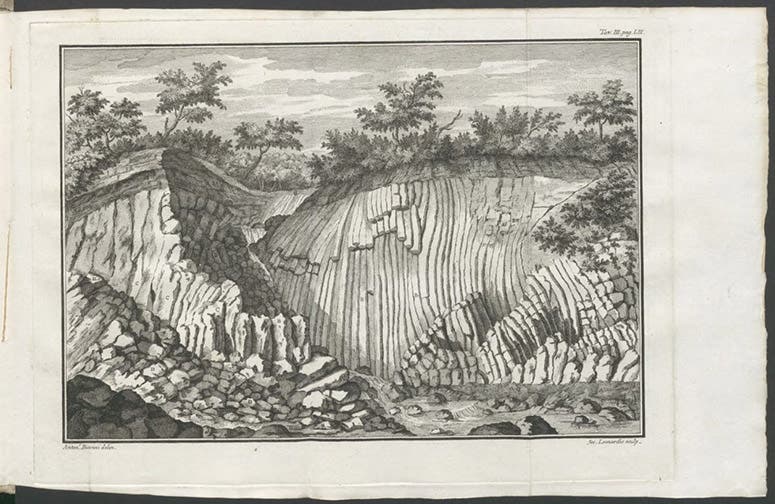

From 1760 to 1777, Fortis explored the rocks of the Veneto, collecting fossils (fifth image, below) and mapping the formations in detail. He was especially interested in the abundance of basalt in the region, both in the form of prismatic columns, and as horizontal beds that intruded into the fossil-bearing sedimentary rock. At the time, most geologists were neptunists, meaning they believed that nearly all rocks, including basalt, formed under water, and little credit was given to volcanoes or igneous processes in rock formation. One exception in Italy was Lazaro Moro, who in 1740 had put forth a vulcanist theory of the earth, giving volcanoes much more of a role in shaping the Earth’s surface than the neptunists were willing to concede. Fortis read Moro. And he knew Arduino. Arduino thought that igneous rock was much more prevalent in the Veneto than previously recognized, and Fortis would confirm Arduino’s suspicion. Fortis became a plutonist, meaning that he believed that other igneous processes within the Earth, besides volcanoes, played an important role in rock formation.

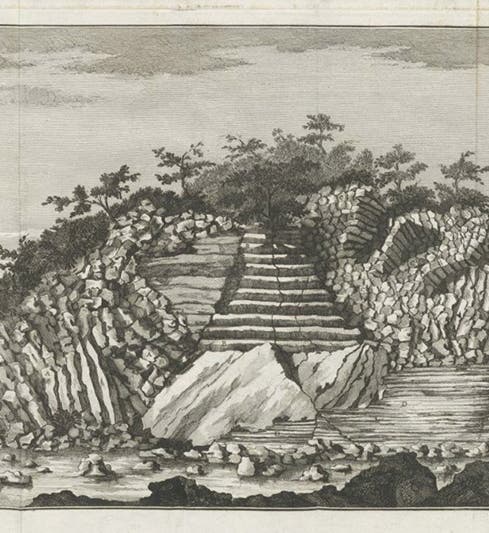

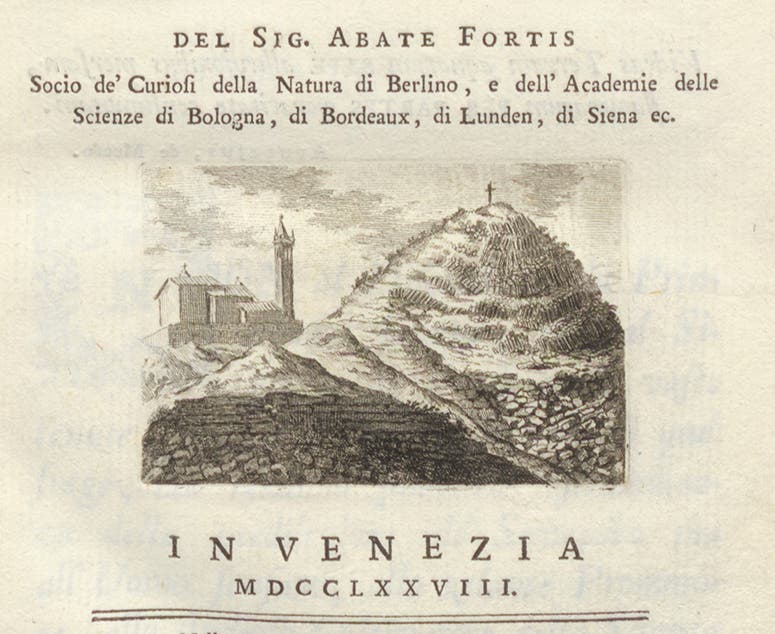

Vallisneri Jr. died in 1777 and Fortis very much wanted to be appointed to the vacant chair of natural history at Padua. He had many colleagues willing to promote him, but he had one serious enemy, a university governor who was ultra conservative, offended by any ideas that ran up against the Mosaic account of creation, and he found Fortis’s geological ideas repugnant. He let it be known that he would quash any effort to install Fortis in the vacant chair. Perhaps in an attempt to show his worth, Fortis published, in 1778, a lovely quarto volume, Della valle vulcanico-marina di Ronca nel territorio veronese memoria orittografica (Orthographical memoires on the Ronca volcanic-marine valley of the Veneto). We show, in addition to the title page (third image), a detail of the lovely engraved vignette, with a basalt formation beneath a church (fourth image). Within the book, Fortis displayed engravings of several of the columnar basalt formations in the Ronca and Alpone valleys (first and sixth images), which he was happy to attribute to volcanoes, following the work of Moro and Nicolas Desmarest in France, whose work he read in the early 1770s. But since Fortis also found many layers of non-columnar basalt sandwiched between layers of marine sandstone in the Veneto, he proposed that perhaps this basalt originated as marine sandstone that had been transformed into basalt by subterranean heat, giving it a plutonic rather than a volcanic origin. This was ten years before James Hutton would propose plutonic origins for the basalts in Scotland.

Fortis tried to keep his more radical ideas about an extensive geological time scale under wraps in his book, perhaps hoping that the governor’s antagonism toward Fortis would cool, but that did not happen. Fortis taught at Padua until his death in 1803, but he never did get to occupy the chair of natural history at Padua.

We displayed Fortis's Della valle vulcano-marina in our exhibition of 2004, Vulcan's Forge and Fingal's Cave: Volcanoes, Basalt, and the Discovery of Geological Time. It has an online presence, but it is not up to the standards of our other online exhibitions. It would be nice to get it updated. The printed catalog, however, is still quite handsome, if I might say so.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.