Scientist of the Day - Carl Edvard Johansson

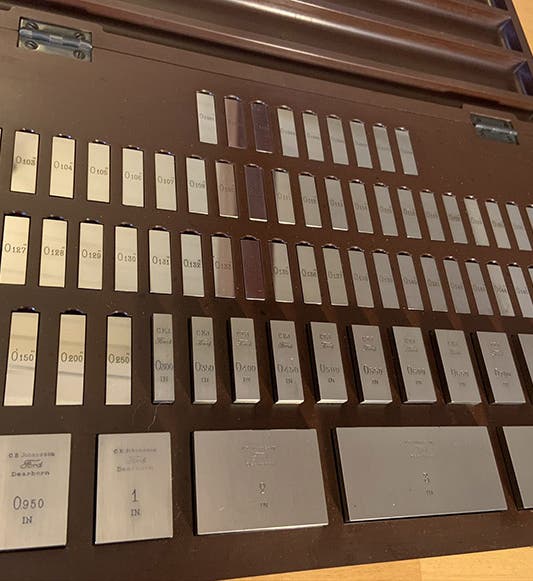

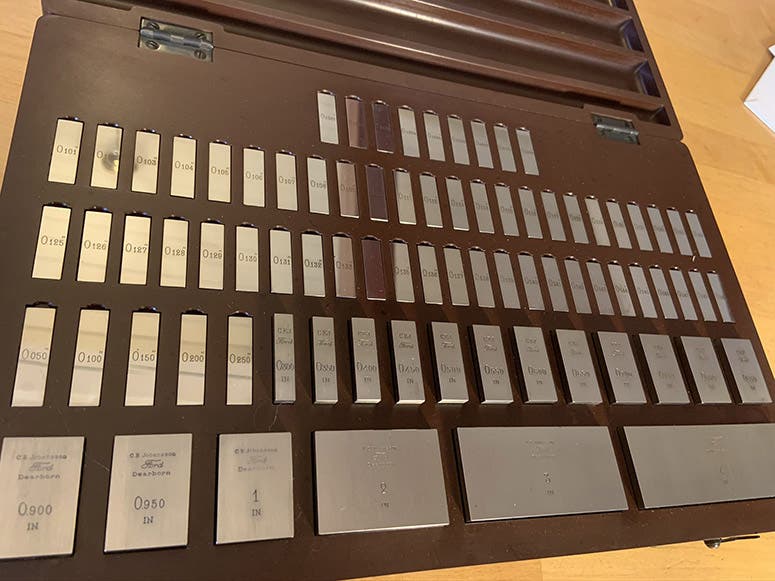

Carl Edvard Johansson, a Swedish tool maker, died Sep. 30, 1943, at the age of 79. In the 1890s, Johansson worked for a rifle factory in Eskilstuna, the steel-making hub of Sweden. Rifle manufacture required more precision than most other kinds of manufacture, and to achieve that precision, it was customary to use gauge blocks, which were lengths of steel bar stock that had been precision ground to a particular length, say 9.2 millimeters (mm), which could then be used to make a rifle part that had to be 9.2 mm. long. Rifle factories had hundreds of these blocks, and every time they retooled, they had to make a new set of gauge blocks. Johansson's bright idea, and it was a very bright idea indeed, was to design a standard set of gauge blocks in a series, so that by selecting the appropriate blocks and combining them, you could make whatever standard length you desired. By 1896, he had completed his first set of gauge blocks, which he rough-cut at work and fine-finished at home, using his wife's sewing machine, fitted with a grinding wheel. His initial set had 102 blocks, and with them it was possible to put together a measuring rod of any length between 0.5 mm and 300 mm, at intervals of 1/100th of a millimeter. If one needed a measuring standard of 22.320 mm, Johansson could assemble one in short order from his blocks, all 102 of which fit neatly into individual slots in a walnut box.

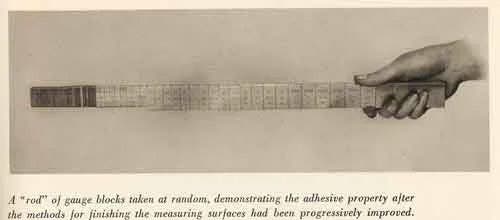

The most astonishing feature of his blocks is that they were so perfectly machined that you could take two blocks, twist them together using a technique called "wringing," and they would adhere, held together by either atmospheric pressure or molecular forces – no one was sure at the time. Thus one could piece together a measuring rod of five separate blocks and, by the time you were done wringing, you had one bar whose 5 constituent pieces were inseparable. No one before Johansson had ground surfaces with such precision that they could be wrung together in such a fashion (third image).

Convincing manufacturers to convert to his block system was difficult at first, because no one believed that Johansson could grind thicknesses to a tolerance of 1/100th of a millimeter, and that his blocks would stick together so resolutely. So Johansson hit the road, travelling from factory to factory, giving demonstrations, and he gradually won adherents. I imagine that the first time a works manager saw Johansson take two blocks from his case and wring them together to form a bar that could not be pulled apart, he was impressed, and when that manager confirmed that the length of that combination bar was accurate to 1/10th of a millimeter, he was further impressed. Johansson sold his first set in 1899, and soon thereafter, the orders started to trickle in, and the trickle swelled to a constant stream.

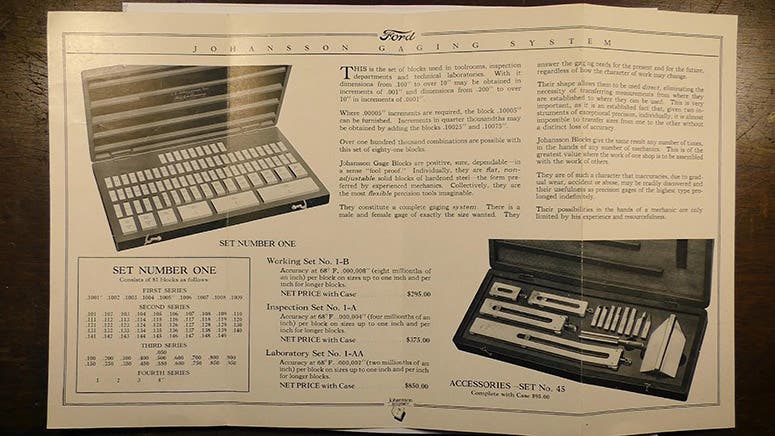

Johansson came to the United States and found a fan in Henry Leland, the head of the Cadillac Automobile Company, who ordered sets of “Jo blocks," as they came to be called, for his engineers, and Henry Ford soon followed suit. Ford became one of Johansson’s biggest boosters. By 1910, Johansson had broken the one-thousandth-of-a-millimeter tolerance barrier, which gave his blocks a precision that even national bureaus of standards, such as the one in Paris where the official meter resides, did not have. Johansson had formed his own company, C.E. Johansson, to produce gauge blocks. When the company ran into financial trouble in 1923, Johansson was bailed out by Henry Ford, and the Johansson company became a division of Ford Motor Company (fourth image). Johansson has been hailed as the greatest innovator in the field of precision measurement since Jean-Laurent Palmer, who invented the screw micrometer in 1848, and the appearance of a set of original Johansson gauge blocks on the auction table will initiate a feeding frenzy among collectors equaled only by that engendered by the sale of an original Palmer micrometer.

There is an early set of Jo blocks in the Science Museum in London (fifth image), although the caption on their webpage is inaccurate – Johansson blocks must always be wrung together – if they are merely held together, the thicknesses do not cumulate properly. There is a set in the American Precision Museum in Vermont that was presented by Henry Ford to Thomas Edison in 1923, and is signed by Edison (first image). I have never visited the Precision Museum – it is high on my bucket list. And there is a set in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, which management insists on calling The Henry Ford, like alumni refer to THE Ohio State University, which is just silly. You can see their set at this link.

There are a number of videos on YouTube that demonstrate the use of gauge blocks and the wringing technique, but most of the patter of the demonstrators is so irritating that I cannot in good conscience recommend any of them. But if you want to take your chances, and you know where your mute button is, just enter “Johansson gauge blocks” in the YouTube search box and have a go: https://www.youtube.com/ . You will soon learn the other meaning of the word “tolerance.”

The only good book on Johansson that I have run across is an old one, C.E. Johansson 1864-1943: The Master of Measurement, by Torsten K.W. Althin (Stockholm, 1948). I read it through the first time I wrote a post on Johansson, years ago; I did not reread it for this one, but I remember thinking it quite excellent. We have the book in the Linda Hall Library.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.