Scientist of the Day - Charles Stanhope

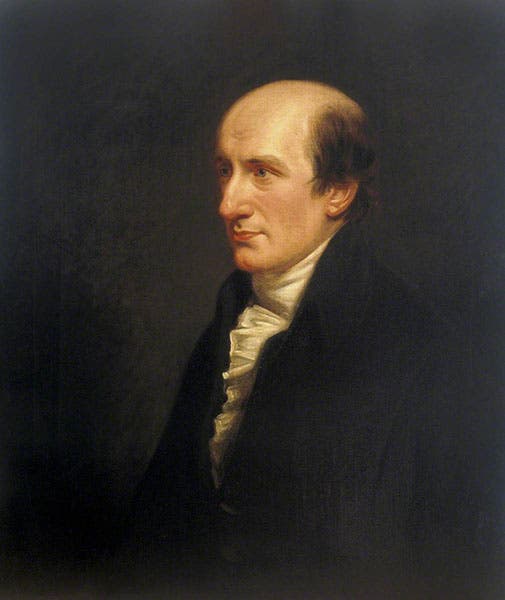

Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Stanhope, an English politician and inventor, was born Aug. 3, 1753. The Stanhopes were one of those wealthy, titled, privileged British families that are good for little but caricature, but Charles was different. He was educated in Switzerland, where he acquired some skill in mathematics and an interest in electricity. Back in England, he was elected to the Royal Society when he was 19 years old, which says a lot about his social class and very little about his scientific expertise. But bless my soul, he published a book on electricity in 1779, Principles of Electriticy, which was translated into French in 1781 as Principes d'électricité, the edition that we have in our collections. The translator was "abbé N." which presumably means abbé Nollet, who was quite a distinguished French electrician. I did not request that Stanhope’s book be scanned, since it is unillustrated, and I am not well informed about Stanhope's contributions to electrical science. John Heilbron had some things to say about Stanhope in his magisterial Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries, but I am unable to transform that into anything that would interest the general reader, so I am going to move on to discuss several Stanhope inventions.

Sometime before 1804, Stanhope invented and had built a printing press constructed entirely of cast iron. Oak and other hardwoods had been the traditional materials for the frame of the printing press since Gutenberg, and it had served well, but with a wooden frame, there is a limit to how much pressure you can apply to the print bed before the frame deforms. A cast iron frame can withstand much more pressure. Reportedly Stanhope’s original iron frame was square, like wooden presses, but when the frames began to crack at the right-angle joints, he substituted a curved cast iron frame which did the trick. The Stanhope press, as it came to be called, was not appreciably faster than the older presses, but it had a wider platen, and it produced clearer, more uniform impressions. The Stanhope press was the hand-press of choice in England, France, and the United States for a long time, and many are still in use. Stanhope did not patent his press, which must have speeded up its dissemination and acceptance. We show a press that was built in 1825 and is on display in the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, Australia (first image). You can see another Stanhope press (and a different portrait of Stanhope) in the article by Jeremy Norman on his excellent History of Information website.

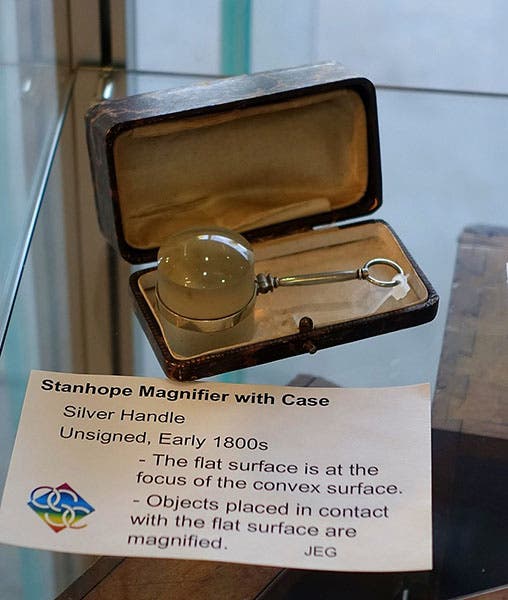

Stanhope's other noteworthy invention was less important in the general scheme of things, but quite popular and worth noting. It was a new kind of magnifying lens, nearly flat on one side and convex on the other, mounted in a small, usually elegant, handle. The design was such that the almost-flat edge was in the focal plane of the convex face, so that if you just laid the flatter edge on whatever you wanted to view and looked through the rounded end, you got a crisp, already focused image. These were very popular in the salon set, and are still made and sold. They are called, unsurprisingly, Stanhope lenses or Stanhope magnifiers. We show one, unusually large, that is on display at the University of Arizona (third image). When we mounted an exhibit of single-lens microscopes in 2008, called Singular Beauty, we had three Stanhope lenses on display, one a fold-up type that you could put in your pocket. But we do not own the magnifiers that we displayed, only the books about them.

Stanhope was a French revolution sympathizer and was usually in political hot water at home. If you search the National Portrait Gallery for Stanhope portraits, you will locate 46 items. But only a few of those are real portraits; the rest are caricatures by the likes of James Sayers and James Gillray, mercilessly lampooning Stanhope and the young French Republic.

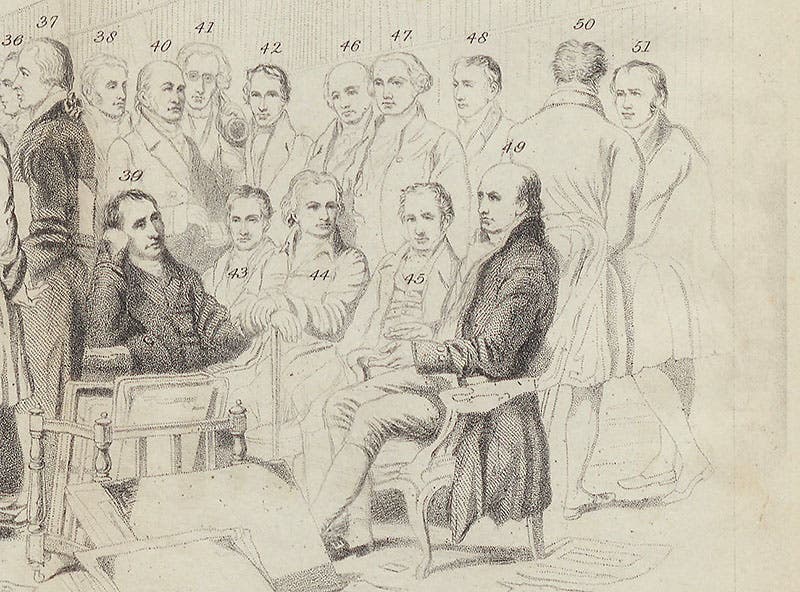

Charles Stanhope (no. 49) and other British scientists, detail of “Men of Science Living in 1807-8,” frontispiece engraving by William Walker, Jr., in his Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science of Great Britain Living in the Years 1807-8, 1862 (author’s collection)

Two days ago, we featured in this space William Walker, who in 1862 engraved a group portrait of significant British men of science alive in 1807-08. Stanhope was one of those 51 men, no. 49 to be exact, and in this detail of the numbered key to the engraving, you can see him sitting, just under his number (fourth image). You can view and enlarge the full engraving on the National Portrait Gallery webpage. If you would like to identify the men surrounding Stanhope, you can find a numbered key at the same site. Stanhope’s likeness in the engraving was taken from a portrait by John Opie, which was then copied by Charles Sibley in the 19th century and is now in the Science Museum, London, and which we used above for our second image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.