Scientist of the Day - Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus, a Renaissance scholar, was born Oct. 28, 1466 (or perhaps 1469). Erasmus was the greatest Christian humanist of the 16th century. He translated the New Testament from the Greek, wrote a tremendously popular book, The Praise of Folly, which attacked excesses in the Church, and then labored to effect reform from within the Church when Martin Luther chose to cleave it from without. Erasmus is not so well remembered for his collection of proverbs, but this may have been his most long-lasting legacy. Erasmus read nearly everything written by the ancient Greeks and Romans, and he began collecting aphorisms. He published his first collection of more than 800 adages in 1500, with a lengthy commentary on each one, and he continued to revise and enlarge his Adagiorum throughout his life; the collection eventually swelled to well over 4000 adages.

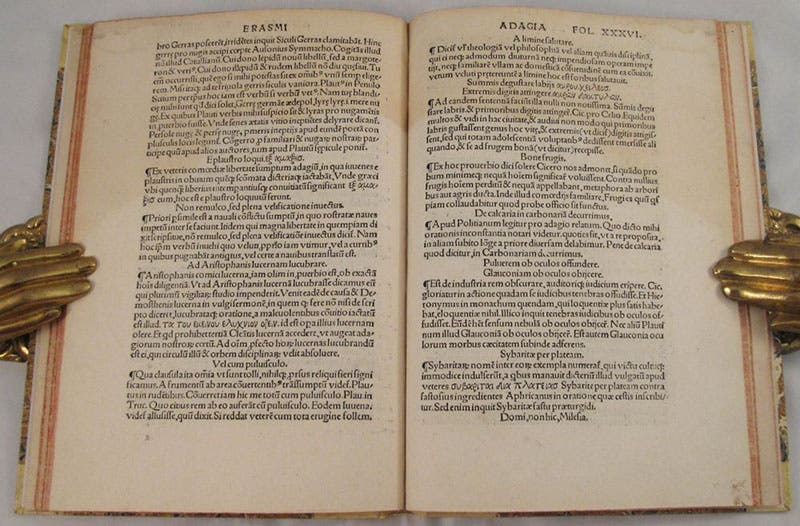

Many Erasmian adages are quite familiar today: Festina lente (make haste slowly), Umbram suam metuere (to be afraid of one's own shadow), Canis in praesepi (dog in the manger), Caecus caeco dux (the blind leading the blind); and should be better known, such as Fecem bibat, qui vinum bibit (he who drinks the wine must drink the dregs). We show a photo of a 1512 Strasbourg edition currently being offered for sale (second image); it is opened to a random page showcasing 11 adages with the commentary of Erasmus. If you look closely on the right, you might make out: De calcaria in carbonarium, the modern version of which is “out of the frying pan, into the fire.” The Adagiorum was often milked for mottos by emblem book writers, after emblems were invented in 1531, and more than a few works of art have an Erasmian adage at their core, such as Pieter Bruegel’s wonderful painting of 1568 (we leave it untitled so as not to spoil the surprise).

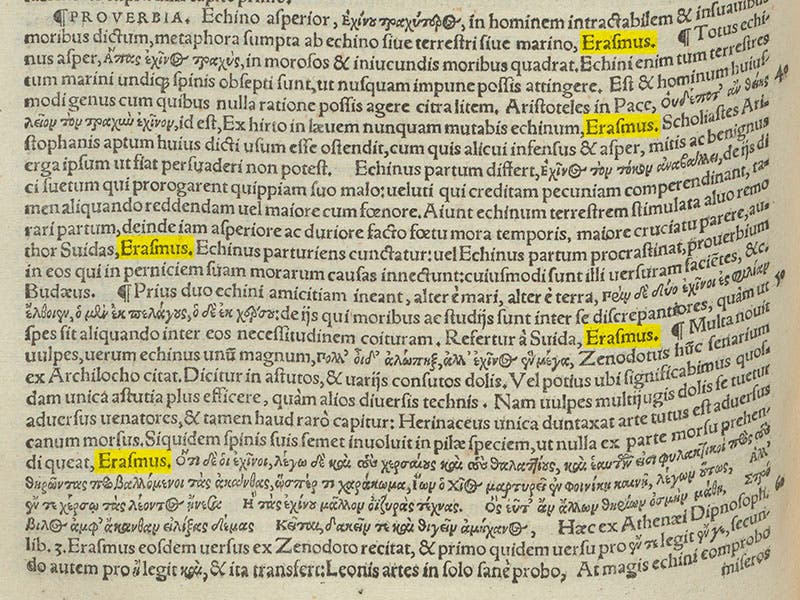

We include Erasmus in a history of science blog because authors of Renaissance natural histories lapped up Erasmus’s Adagiorum. Since the Renaissance view of natural history embraced every kind of animal association, including emblems, hieroglyphics, fables, mythology, coins, and proverbs, the Adagiorum was a godsend, since all of the animal proverbs were now in one place. We show you part of a page from Conrad Gessner’s article on the hedgehog in his Historia animalium (1551), where he discussed hedgehog proverbs, and the name Erasmus is cited 5 times (fourth image). One of the proverbs that Gessner took from Erasmus: Multa novit vulpes, verum echinus unum magnum – “the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” – was later the subject of a book by Isaiah Berlin that we once discussed in this forum. We also show Gessner’s woodcut of a hedgehog from the same article, because it seems so cutely smug about its one big thing (third image).

One of the proverbs published by Erasmus was Leonem ex unguibus aestimare (know the lion by his claws). This adage played an interesting role in a famous incident a century and a half later, involving Isaac Newton. In 1696, the Swiss Scholar Johann Bernoulli had circulated a pair of problems among European mathematicians and challenged them for a solution, but after six months, no solution was forthcoming. Newton first heard of the problems late one afternoon in 1697, and he solved them both that very night. He sent the results to the president of the Royal Society, asking that they be published, but anonymously. When Bernoulli saw the solution, he guessed immediately that it was Newton’s work, explaining ex ungue Leonem, I know the lion by his claw. Erasmus’s Adages have recently been published in English translation in 7 fat volumes, for anyone who is searching for just the right turn of phrase for a particular occasion. Whatever you are looking for, It has to be in there somewhere.

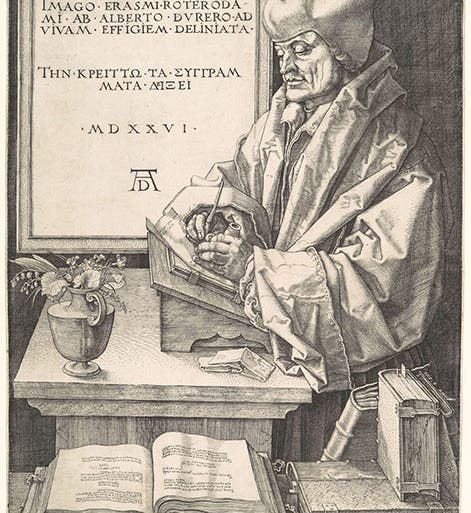

Erasmus is remembered by an abundance of penetrating portraits by the finest artists of northern Europe. There are at least four by Hans Holbein, of which I have selected one of 1523 in the National Gallery of London (fifth image); there is another by Quentin Massys (1517) in Rome; and a 1526 engraving by Albrecht Dürer, a print of which is in the Met (first image). If you prefer your heroes in the round, it is hard to beat the statue in Erasmus’s birthplace of Rotterdam, which has withstood numerous invasions and bombings since its erection in 1622 (sixth image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.