Scientist of the Day - Isaiah Berlin

Bill Ashworth

Bill Ashworth

Isaiah Berlin, a British historian, was born June 6, 1909. Berlin was one of the most eminent historians of his generation, but we focus today on one of his lighter pieces, which he published in 1953: The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History. In this short work, as a prelude to his analysis of Tolstoy, Berlin divides the world of thinkers and doers into two groups: hedgehogs and foxes. The idea comes from a proverb that everyone ascribes to the ancient Greek Archilochus but which in fact everyone takes from the Adages of Desiderius Erasmus, who took it from Pliny the Elder. In Erasmus's formulation, the adage is: Multa novit vulpes, verum echinus unum magnum – “the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing.” The point is that the fox is clever and has many schemes to catch prey and avoid predators; the hedgehog, on the other hand, has but one means of defense, rolling up into a prickly ball, but it is supremely effective. Berlin proceeds to gives us example of historical hedgehogs and foxes – Plato was a hedgehog, for example, while Aristotle was a fox – en route to his point that Tolstoy was really a fox by nature but wanted to be a hedgehog, and that was the source of his difficulties.

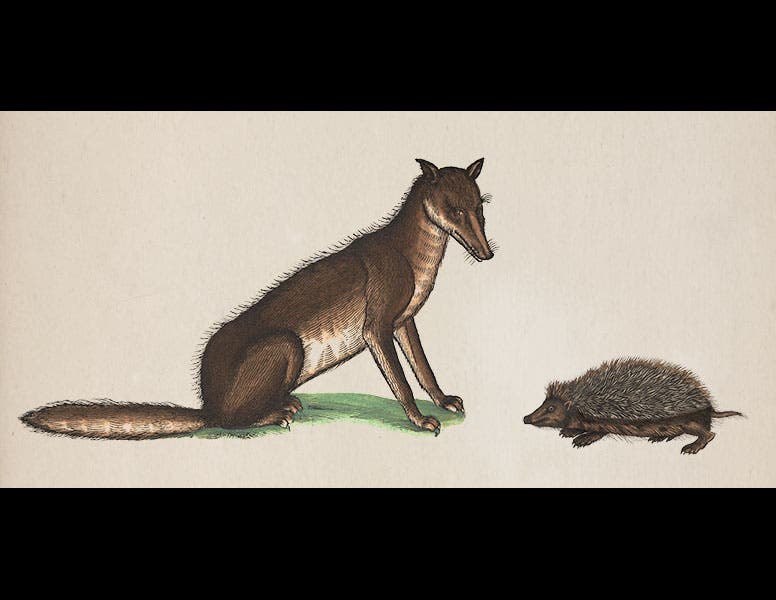

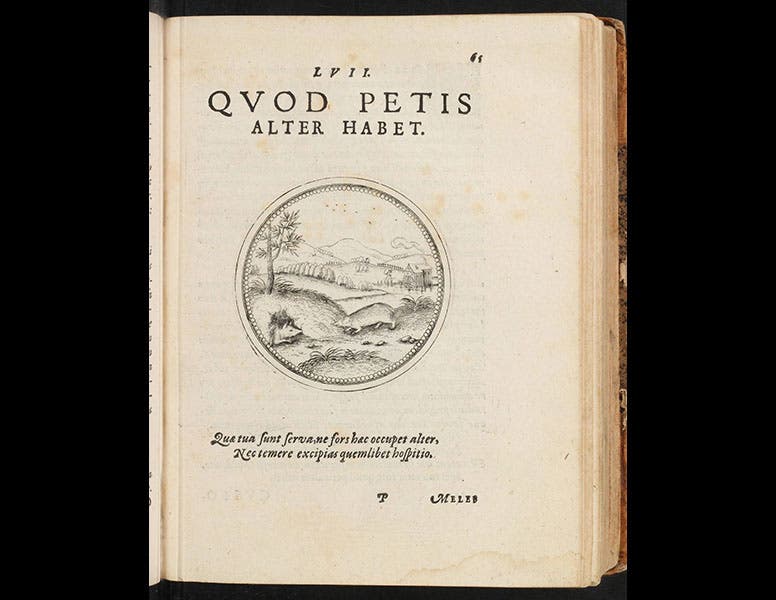

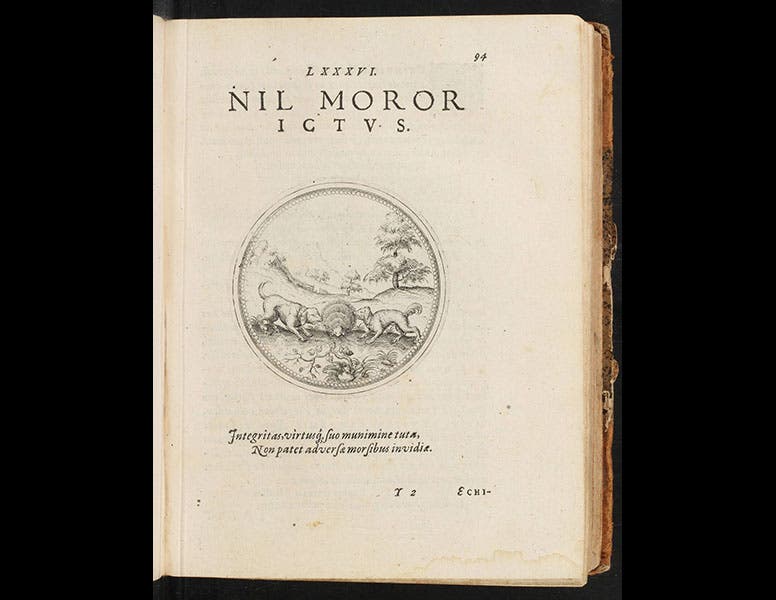

Berlin did not intend for his argument to be taken as seriously as we tend to take it, so for this occasion we adopt a lighter approach and illustrate the proverb (and his book) with a few hedgehogs and foxes from our collection. The first image is a composite, showing hand-colored woodcuts of a fox and a hedgehog from our copy of Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium (1551). We had to flip the hedgehog to make him look at the fox, and then shrink him to scale. We do not own any of the many editions of Erasmus's Adagia, and the work is not illustrated anyway, but we do have a copy of an animal emblem book by Joachim Camerarius, Symbolorum & emblematum ex animalibus quadrupedibus... centuria (1595). There are three fox emblems in the work--fittingly, since the fox knows many ways--and we show here the one depicting a fox who has waited for a badger to leave his lair and has then moved in, with the motto: Quod petis alter habet – “what you want, another has” (third image). There are actually two hedgehog emblems – belying the claim that it knows only one thing – but we show the famous one, a hedgehog hunkered into a ball against the hounds, with the motto, Nil moror ictus – “I do not mind the blows” (fourth image).

Finally, since I happen to own it, we display a Viennese bronze of a hedgehog about to show a fox his one big thing (fifth image). In daily life, it sits on the shelf right next to my copy of Berlin’s book (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)