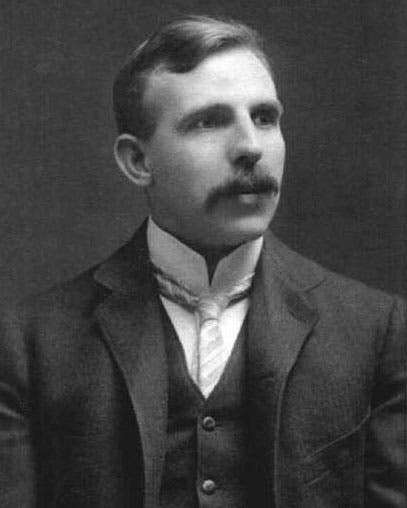

Scientist of the Day - Friedrich Dorn

Friedrich Ernst Dorn, a German physicist, was born July 27, 1848. Dorn taught experimental physics at Halle, and his life and career, while distinguished, was not especially noteworthy. He is remembered primarily for a discovery that, it turns out, he did not make.

It is curious how historical errors can linger on in the literature. The most notorious example is the oft-repeated statement that people at the time of Columbus believed that the Earth is flat, and that his sailors feared falling off the edge of the Earth. It has been demonstrated numerous times that while one can find a few instances in early medieval Europe of individuals advocating a flat Earth, by the later medieval period it was universally understood that the Earth is a sphere and, moreover, that one can prove this from facts derived from sailing and the observance of eclipses. Yet the chances are good that one of your children's textbooks states that Columbus proved the Earth is round.

Now since secondary school textbooks are written by textbook writers, who rely mostly on earlier textbooks for their facts, and who are not conversant with studies written by historians of science, such inertia is understandable (if not quite forgivable). But occasionally errors are repeated by reputable scholars who would know better if they simply read the literature they included in their bibliographies, instead of repeating statements derived from secondary literature. Which brings us back to Dorn. The first sentence of the Wikipedia article on Dorn says: “Friedrich Ernst Dorn ... was a German physicist who was the first to discover that a radioactive substance, later named radon, is emitted from radium.” This statement could have been derived from a variety of sources, the most likely being Mary Elvira Weeks, The Discovery of the Elements (my edition is 1934), where, after commenting that the Curies had noticed that air which comes in contact with radium becomes radioactive, Weeks says: “The correct explanation was first given in 1900 by Friedrich Ernst Dorn… Professor Dorn showed that one of the disintegration products of radium is a gas. This was at first called radium emanation, or niton, but since it is derived from radium, the modern name radon is to be preferred.” She cites a paper by Dorn in the Abhandlungen for 1900 of the Naturforschenden Gesellshaft of Halle.

In 2003, a husband-and-wife team, J.L. and V.R. Marshall, decided to take a new look at the discovery of radon. The novelty of their approach – which should not be a novelty – is that they read all the original papers. They discovered that all Dorn said in his paper is that radium gives off an emanation that is radioactive. He said nothing about a gas, and he did not call it radium emanation. And he did not propose that it was a new element. In truth, Ernest Rutherford had already discovered that thorium, another radioactive element, gives off an emanation, whose radioactivity persists for a minute or so. Rutherford (and his colleague, Frederick Soddy) found that the radioactivity of the emanation from radium lasts longer, and that it leaves a deposit on the container in which it is held. By 1902, Rutherford and Soddy came to suspect that the thorium emanation is not only a gas, but a new element, and when they studied the radium emanation (a term first used by Rutherford, not Dorn), they came to the same conclusion. The new element was first isolated by William Ramsay in 1909, who called it niton and determined its place in the periodic table, just below xenon. It was not until 1923 that the committee that decides such things settled on the name radon.

So all it took to determine that Dorn did not discover a new element, or even claim to have done so, was to read his paper of 1900. The Marshalls made a big deal of the fact that they travelled all the way to Halle to find the original journal containing Dorn’s paper. I felt quite smug when I read that, and said to myself, they should have come here – we have nearly every scientific journal ever published. But I was wrong – we do have the Abhandlungen of the Halle Natural Research Society, but we do not have the volumes from the period around 1900. If we did, I would have photographed Dorn’s paper for the occasion.

It has been almost 20 years since the Marshalls published their paper – one would think that the attribution of the discovery of radon to Dorn would have ceased, or at least subsided. But it hasn’t, really. The Wikipedia article on Dorn does, at the end, discuss the Marshall paper and its implications for Dorn. But no one has gone back to rewrite the mistaken first sentence. If you would like to read the Marshall's paper, it appeared in the Bulletin of the History of Chemistry, 2003, vol. 28(2), pp. 76-83, and you can find it online here.

So it appears that Friedrich Dorn should not be a Scientist of the Day. But I had to give him that honor, in order to tell the story of why he does not deserve that honor. We are the victim of a new catch. That is some catch, that Catch-23.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.