Scientist of the Day - Henri Poincaré

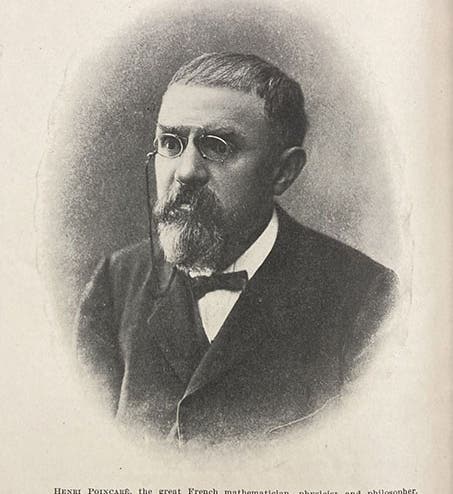

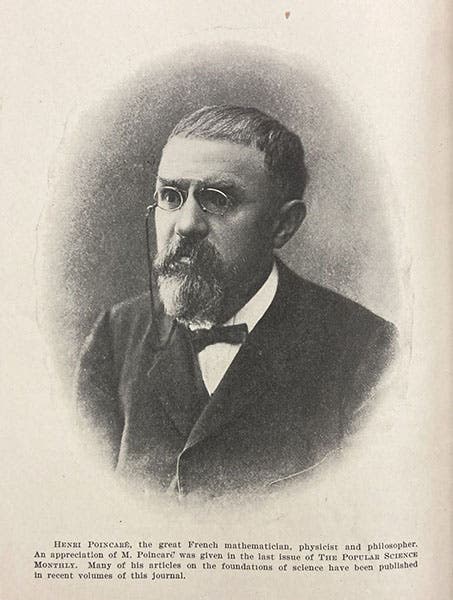

Henri Poincaré, a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, and philosopher of science, died July 17, 1912, at the relatively young age of 58. Poincaré came from Nancy, demonstrated considerable mathematical skills in the Lyceum there, and by 1881 was on the faculty of the Sorbonne in Paris, where he would teach until the end of his life. There are some formidable mathematicians, like Bertrand Russell, who have called Poincaré the greatest French mathematician of his era, and others, such as Karl Popper, who considered him the outstanding philosopher of science of his times, and I trust their opinions, but cannot speak to either subject personally. So let me dwell on a few aspects of Poincaré's life that I know a little more about.

Poincaré went to work for the Bureau of Longitude in 1893, advising them on setting up universal time zones. This aroused in him an interest in local time, and in clocks, and in the problem of synchronizing clocks, since light travels at a finite speed. When a Dutch physicist, H. A. Lorentz, came up with a set of equations that would transform distance and time when you moved from one reference system to another, Poincaré lent his mathematical support and encouragement. This was all before 1900. If any of this sounds familiar, it is probably because in 1905, one year after Lorentz had published a paper on local time and his transformations, and Poincaré had coined the term “principle of relativity” in a public lecture, Albert Einstein published his famous paper on special relativity, in which he used Lorentz transforms to show that distance and time change as one moves from one frame of reference to another, and there is no such thing as absolute time or absolute space. In his paper, Einstein did not cite Poincaré or Lorentz – in fact, he didn't cite anyone. Consequently, more than a few historians and physicists have credited Poincaré and/or Lorentz with discovering special relativity. I have my doubts, because neither Poincaré nor Lorentz abandoned the idea of a universal ether as a medium for electromagnetic radiation, which Einstein did, and which you need to do for true relativity. But it was and is a curious situation.

Poincaré is also intriguing because of his phenomenal memory. He had very poor vision, so at lectures he could not see blackboards or lantern slides. But he could remember everything he heard, and everything he ever read. He was not a savant at calculating, able to tell you the square root of some 16-digit number. But he could calculate for hours, and rarely made mistakes. His contributions to pure math were prodigious. Wikipedia even has a page titiled: “List of things named after Henri Poincaré.” Most of the items listed – and there are many – are mathematical theorems or conjectures.

Poincaré is often described as a polymath, but he really wasn't, if you require that a polymath have skills or expertise in a variety of disparate disciplines, as Humboldt did, or Leibniz. But in the mathematical sciences, Poincaré was indeed a master of them all – astronomy, physics, thermodynamics, mechanics, navigation, and pure mathematics. The only thing missing from his resume was a major discovery, like electromagnetic radiation, or quantum theory, or the nuclear atom. So although he was nominated for a Nobel Prize dozens of times, Poincaré never received the award. There was apparently no single achievement that the Nobel committee could point to as the basis for a prize. And then his early death, from an embolism after surgery, put that out of reach forever.

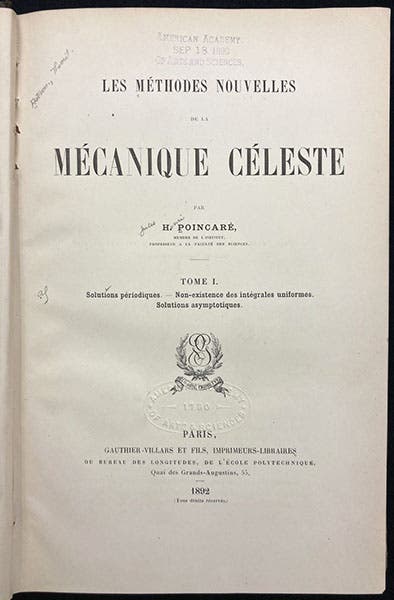

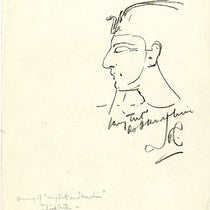

When I was in graduate school, and took a course on 20th-century physics, I don't think Poincaré was mentioned even once – it was all Maxwell, Planck, Einstein, Bohr, and then the quantum boys of the 1920s. That was and is too bad; Poincaré deserved better at the hands of historians. I am happy to report that he is now getting his due, with two major English language biographies in the past 15 years. We have a dozen original editions of books by Poincaré in our library (second image), and even more in later English translations.

Poincaré was buried with his wife in Montparnasse cemetery in Paris (fourth image). There was talk a few years back of moving his remains to the Pantheon, the resting ground in Paris for many French worthies, but nothing seems to have come of it, and that is just as well. We can find better ways to honor newly appreciated heroes other than by moving them from cemetery to cemetery.

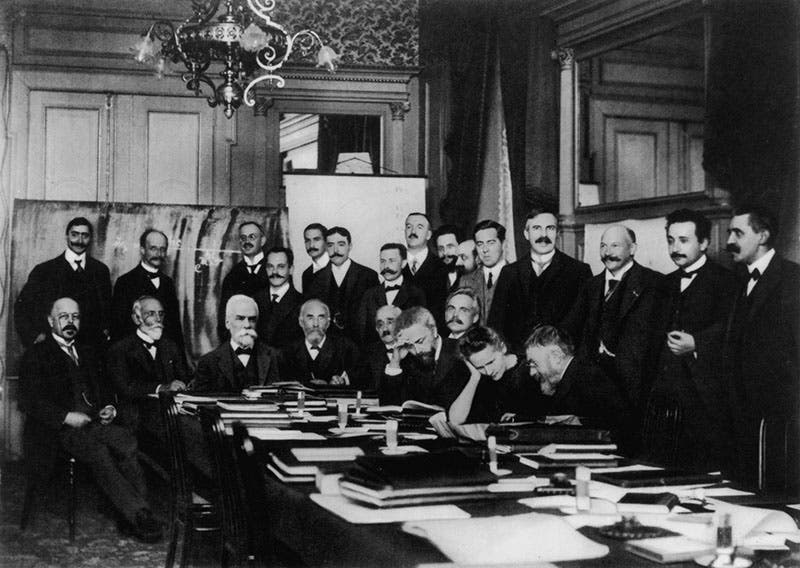

Probably the best-known photograph of Poincaré is one in which he is seldom recognized. It is a group portrait of the participants in the first Solvay Conference in Brussels in 1911 (fifth image). Viewers immediately notice Marie Curie at right, and Einstein behind her, and perhaps Planck, and Ernest Rutherford. But Poincaré is right there, discussing some matter with Madame Curie and fully engaging her attention. You may see a close-up centered on Curie as the last image in our post on Jean Perrin, seated on the other side of Madame Curie.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.