Scientist of the Day - Henry Bryant Bigelow

Henry Bryant Bigelow, an American marine biologist and science administrator, was born Oct. 3, 1879, in Boston and died on this day, Dec. 11, 1967, in Concord, age 88. He came from a well-educated and tolerant family who did not begrudge Henry's passion for hunting and fishing and climbing mountains, as long as his schooling did not suffer, which it did not. He graduated from Harvard in 1901 and received his PhD in biology in 1906.

The decisive event in determining the direction of Henry's career came in 1901-02, when he accompanied Alexander Agassiz, professor at Harvard and son of Louis Agassiz, on a voyage to the Maldive Islands. On this expedition, Bigelow discovered marine biology, oceanography, and Cnidaria (jellyfish), which he was responsible for preserving and describing. He was a marine biologist from that point on.

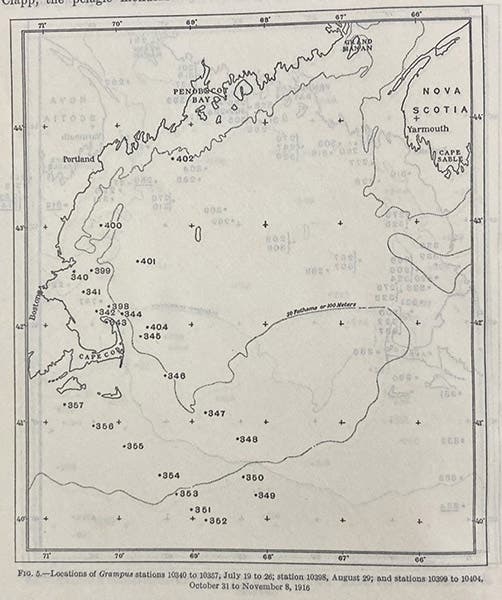

After receiving his degree, Bigelow became part of a long-term project to study the Gulf of Maine, the large body of water that lies between Cape Cod and Nova Scotia, about which no one knew anything (see map, third image). The goal was to discover what lives there, what the physical conditions are like all the way down to depth, and how the life-forms interact with one another. They had access to a Bureau of Fisheries ship, the Grampus, until 1917, and one of the few photos we have of a younger Bigelow shows him at the helm of this ship (first image). Bigelow slowly took charge of this survey, which lasted until 1924, and produced three important monographs, one on fish, one on plankton, and one on oceanography, published in the Bulletin of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. We have the two volumes that contain these three monumental papers, two of them over 500 pages each, and I marvel at the fact that Bigelow wrote two of them all by himself, and most of the third.

Bigelow and his colleagues were doing oceanography. The problem was that oceanography had no real institutional base in the United States. It is usually said that oceanography as a science began with the voyage of the Challenger in 1872-76. This may have been true in Europe, but it does not seem to have changed anything in the U.S.

So in 1927, a committee was convened by the National Academy of Sciences to address the problem. Bigelow was secretary. The committee decided that what was needed was an independent institution devoted to the study of the world’s oceans, and Bigelow wrote up the Report, which was later released to the public in a simplified form (fourth image). The recommendation was accepted, and in 1930, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) was founded at the southwestern tip of Cape Cod. There was already a biology lab there, the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, but that was a completely different institution, with no focus on oceanography. The WHOI was interested in far more than discovering new species. The goal was to understand how the oceans work as a collection of ecosystems. And the first Director of WHOI was Henry Bigelow, one of the first to see the need for such an institution.

In his 9 years of leadership, Bigelow helped define American oceanography. He was insistent that the field needed chemists, physicists, and geologists, in addition to marine biologists, and that they needed sea-going experience, every one of them. He commissioned and had built the WHOI’s own research vessel, the Atlantis, an outline of which can be seen today in the institution’s logo (fifth image).

Bigelow shaped and defined the early years of WHOI, but others took the helm when he resigned in 1939, trading in administration for a return to marine biology, and he is not as remembered today as he should be, for an oceanographic pioneer. It would have helped his image if he were more flamboyant, like Ernest Rutherford storming through the Cavendish Lab at Cambridge, or if there were colorful stories associated with his leadership or scholarship, but there are not. There are several awards in oceanography named after Bigelow, and now he has a ship named in his honor, the NOAAS Henry B. Bigelow, a handsome vessel launched in 2005 (seventh image).

Henry Bigelow was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass., under an attractive headstone; he is not too far from the grave of the great American proto-oceanographer, Nathaniel Bowdich.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.