Scientist of the Day - Joseph Leidy

Joseph Leidy, the first great paleontologist of the United States, was born on Sep. 9, 1823. He was a Philadelphian and was associated with the Academy of Natural Sciences of that city for most of his life. He is best known for discovering the first dinosaur bones in the United States in 1856, and then describing a new dinosaur, Hadrosaurus, whose remains were found in New Jersey in 1858. We discussed the dinosaur side of Leidy’s life in a post on Leidy four years ago.

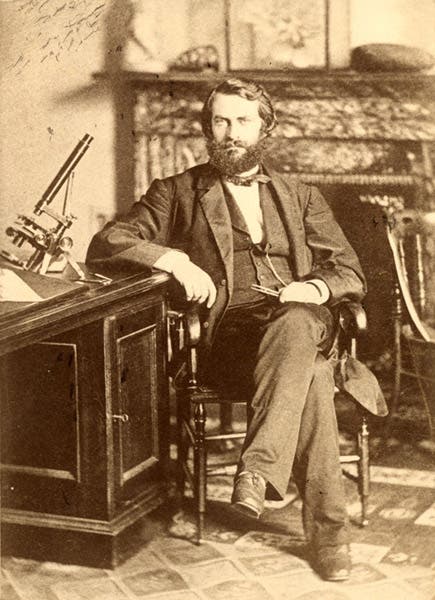

Portrait of Joseph Leidy, undated photograph, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia (photo courtesy of Robert M. Peck, Academy of Natural Sciences)

But in 1855, Leidy published a volume that was more indicative of his considerable paleontological skills. It was what we would now call a monograph, and its intent was to sort out all the various remains that had been found in North America of giant sloth-like animals. It is a large slim quarto that he called, A Memoir on the Extinct Sloth Tribe of North America, published by the young Smithsonian Institution. We have two copies in the library, one in our Government Documents collection, and one in the History of Science collection. We discuss and illustrate the later copy today, which Leidy presented to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston (third image), and which came to us, with the entire Academy library, in 1946.

The first remains of a giant ground sloth were discovered in South America and brought to Spain, where they were mounted and described by Juan Bautista Bru de Ramon in 1796, and then again by George Cuvier in 1804 and 1812, who named it Megatherium. Other specimens were found in South America by William Clift, Woodbine Parish, and even by Charles Darwin on the voyage of HMS Beagle.

But none of these were North American. The first such remains found in the United States were some claws, metatarsals, phalanges, and leg bones, which were found in Virginia and given to President Thomas Jefferson, who in 1797 read a brief notice about them to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, which was then published in their Transactions in 1799. Jefferson thought, because of the claws, that they were the remains of some large carnivore. But the anatomist Caspar Wistar of Philadelphia published a more detailed paper on the specimens in the same volume of the Transactions, in which he noted the similarity to edentates like the sloth. He also pictured some of the smaller bones in an engraving (fourth image). In 1825, the American naturalist Richard Harlan named the animal, Megalonyx jeffersonii, the name by which it still goes.

The original Megalonyx bones described by Caspar Wistar in 1799, and preserved at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, here arranged as they were depicted in Wistar’s plate 1 (see previous image) (photo courtesy of Robert M. Peck, Academy of Natural Sciences)

For his monograph, Leidy began with Jefferson’s bones, which he arranged to have transferred to the Academy of Natural Sciences. But he also assembled around him all the sloth-like fossil remains that had been found in the 50+ years since Jefferson, many of which belonged to Megalonyx, but some of where clearly were the remains of other genera. And when I say, “around him,” I mean that quite literally. Everyone who had fossils that resembled Megalonyx or Megatherium, many living out in Kentucky and Indiana and even further west, sent them to Leidy, who in turn deposited them in the Academy. He lists them all, thanking every contributor, in his book.

One of Leidy’s principal sources was David Dale Owen, a geologist in New Harmony, Indiana (Owen’s father was Robert Owen, founder of the utopian community). The skull and jaw of Megalonyx that Leidy depicted (first and seventh images) were from a specimen sent to Leidy by Owen. Owen went on to conduct the first geological surveys of half-a-dozen midwestern states, all of which we have in our collections, so he is certainly a good candidate for a future post.

Monographs about specific families of animals, especially extinct ones, were not yet common in 1855, even in Europe. Cuvier had written several very short descriptions of mammoths, mastodons, and the megatherium, but they were not really monographs, since he did not have access to that many specimens. Richard Owen was really the first to write a monograph on an extinct animal, which just happened to be a giant sloth, one he called Mylodon, or more fully, Mylodon darwinii, since his monograph was based on a specimen brought back by Charles Darwin from South America. We showed several images from this book, published in 1842, in a post on Owen, and included his most spectacular illustration, a fold-out reconstruction of a Mylodon skeleton with a modern sloth skeleton for comparison, which you may see as the first image at the link.

So Leidy’s monograph on North American giant ground sloths was the second such monograph, and the first by an American. Owen would make it a trifecta in 1860, when he published Memoir on the Megatherium, prompted by a newly excavated skeleton, which Owen again reconstructed in an arresting fold-out engraving. We just scanned this book in anticipation of another post on Owen at some appropriate future occasion.

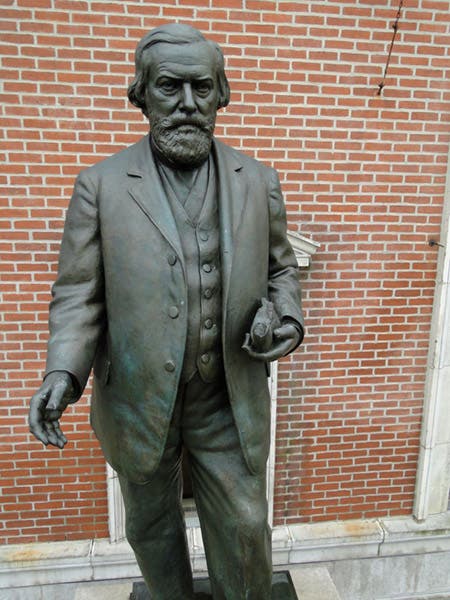

Statue of Joseph Leidy, bronze sculpture by Samuel Murray, 1907, now in front of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia (photo courtesy of Robert M. Peck, Academy of Natural Sciences)

There is a statue of Leidy, sculpted by Samuel Murray in 1907 and installed initially at Philadelphia’s City Hall Plaza, then moved to the front of the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1929. In our first post on Leidy, we linked to a Flickr photo of this statue, which wasn’t very good. Robert Peck, Curator of Art and Artifacts and a Senior Fellow at the Academy, sent me some much better close-up photos of the statue, from which I chose one (eighth image). He also sent the photo-portrait that we used as our second image, and a wonderful photo of the original bones of Megalonyx, handled by Jefferson and Wistar, and still to be found in the Academy’s collection (fifth image). They have been arranged to duplicate the layout depicted in Wistar’s first 1799 engraving (fourth image). It really belongs in our post on Wistar, but since I have no immediate plans to redo that post, we happily include it here. I very much appreciate Bob’s help in enriching this post, as he has done many times in the past.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.