Scientist of the Day - Karl Zimmer

Karl Günter Zimmer, a German radiation physicist interested in the effects of radiation on organisms, died Feb. 29, 1988, at the age of 76. In 1935, when he was only 24 years old, he teamed up with two older scientists, geneticist Nicolai V. Timoféeff-Ressovsky and quantum physicist Max Delbrück, to publish a long paper on what can be learned about the mechanism of inheritance by irradiating organisms and causing mutations (Hermann Muller had discovered that radiation causes mutations in 1927). The paper was very statistical, and to me nearly unreadable, even in translation. Each man wrote a chapter, and then they wrote the conclusion together. The paper was called “Über die Natur der Genmutation und der Genstruktur," (On the nature of gene mutation and gene structure), and it was published in the first volume of a new series, Biologie, spun off an old journal, the Nachrichten (Reports) of the Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen (Scientific Society of Göttingen). The splinter journal never got beyond volume 1. It is often said that the journal is very scarce and unobtainable, which is why the paper was seldom read until 1944, but any Library that subscribed to the Nachrichten would have received it – the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston got a copy in the mail in 1936, and it passed to us in 1946, along with the rest of the Nachrichten. We, unfortunately (in our first naïve months of existence), had the Biologie issues sewn up in a rust-colored buckram-bound volume, discarding the green paper covers of each issue. But we do have the paper.

The paper turned out to be a milestone work, so much so that it is universally referred to as the "Three-Man Paper," and even more succinctly, 3MP. Some call it the Green Paper, because of the paper covers that we longer have. The Three-Man paper was one of the first publications to assume that the gene is a molecule of atoms, and to propose that we can learn about its structure by bombarding it with X-rays, possibly even calculating the size of a gene by the physical extent of the mutations. This was 18 years before the riddle of gene structure was solved by James Watson and Francis Crick. In some ways, the Three-Man Paper marked the beginning of molecular biology, although the term would not be coined for another three years. And since two of the authors were physicists, it was the harbinger of a new effort to understand biological phenomena by applying the principles of quantum mechanics.

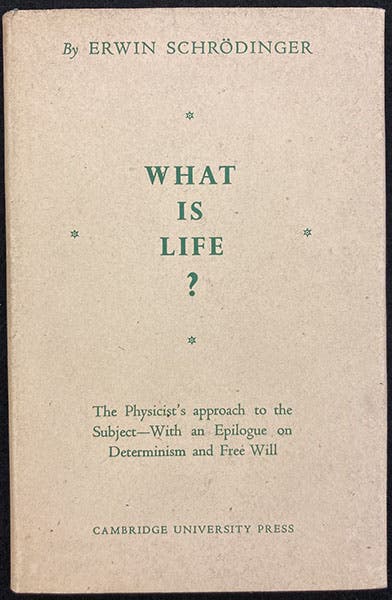

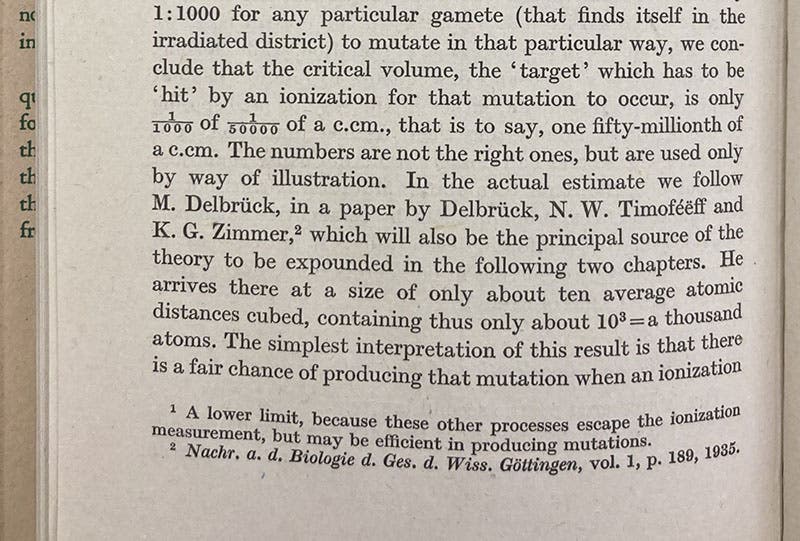

The Three-Man Paper remained obscure and not-often cited until 1944, when Erwin Schrödinger, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, published a small book with the engaging title, What is Life?, in which he too pointed out that many of the problems faced by biologists in attempting to understand life can be attacked from the vantage point of physics, especially quantum mechanics. And in his book, Schrödinger gave credit to the Three-Man Paper for being the first to raise this possibility. Since What is Life? attracted wide-spread attention from the new wave of molecular biologists (Watson and Crick both credited the book with inspiring their search for the structure of DNA), so too, now, did the Three-Man Paper, and suddenly biologists (and physicists), who had never heard of the paper, began to seek it out. I doubt that any biologist could read it, but they could cite it, and give it its common name, the Dreimännerarbeit (Three-Man Paper).

Dust jacket of What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell, by Erwin Schrödinger, first edition, 1944 (author’s copy)

Detail of page 44 of What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell, by Erwin Schrödinger, 1944, citing the Three-Man Paper (author’s copy)

I am not sure how Schrödinger was able to write and publish his book in 1944, with the War going on – perhaps it was the only kind of book one could write during wartime, and he was in Dublin, not Berlin. Zimmer was otherwise occupied, until Berlin fell in 1945 and he was shanghaied by Soviet troops and taken back to Russia, where he was forced to work on their atomic bomb project. He remained in Russia for ten years under Gulag-like conditions, and was only able to return to Germany in 1955, where he found that Max Delbrück, working in the United States, had eclipsed all of the "three men" in fame. Zimmer lived out the rest of his life directing, until retirement, the Institute for Radiation Biology in Karlsruhe.

The Three-Man Paper remained more cited than read until Philip R. Sloan and Brandon Fogel published Creating a Physical Biology: The Three-Man Paper and Early Molecular Biology (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2011), which contains a complete translation of the paper by Fogel and six articles about the history and importance of the paper. The dust jacket of the hardbound edition not only has photographs of the three authors (Zimmer is at the right, Delbrück at the bottom), but it is colored green, in honor of the original issue, a nice touch. We have this book in our library as well. Since our copy has a protective mylar cover and does not photograph well, I have used a photo supplied by the Univ. of Chicago Press, which is identical to ours, down to the fake white tear at bottom left, which must be an artifact of the original Green Paper that was used by the translators.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bivouac on Jan. 26 [1854], chromolithograph from a sketch by Balduin Möllhausen, Explorations and Surveys for a Railroad Route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean: Route near the Thirty-Fifth Parallel, by Amiel W. Whipple (Pacific Railroad Report, 3), 1856 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/55140a90-4b5d-4dac-832c-5def5cb51a10/Whipple1_cover.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)