Scientist of the Day - Milutin Milankovic

Milutin Milanković, a Serbian mathematician, died Dec. 12, 1958, at age 79. Milanković (sometimes spelled Milankovitch in English accounts) was born in Austria-Hungary to Serbian parents, in what is now Croatia. He studied engineering in Vienna and then practiced as an engineer for some years – his specialty was reinforced concrete. But in 1909, he was offered a position as professor of applied mathematics at the University of Belgrade, and he leapt at the chance to return home, even though all of his colleagues tried to dissuade him from giving up sophisticated Vienna for provincial Belgrade. But Milanković was proud of his Serbian heritage and accepted the offer.

When the Great War broke out, Milanković was imprisoned, but he was eventually paroled to Budapest, where the police kept an eye on him, but where he was able to work. He wanted a long-term project that required his considerable mathematical skills, and he chose climate change – specifically, the role that variations in the Earth’s orbit might have on climate, and whether such changes might have caused the Ice Ages.

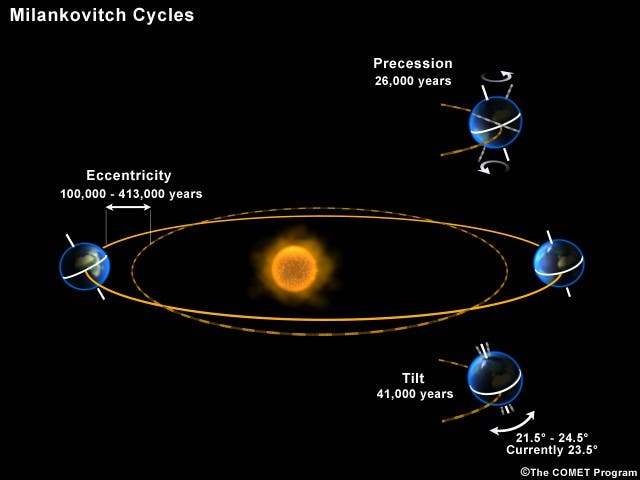

It had been known since the Copernican revolution of the 16th century that the Earth's orbit around the Sun changes in a complicated manner (it was actually known long before the Renaissance, but it was thought to be the Sun's orbit and the tilt of the ecliptic that were varying). The orbit of the Earth changes shape, going from a fatter ellipse to a thinner one over a period of about 100,000 years; this cycle is called change in eccentricity (see diagram, third image). The tilt of the Earth's axis with respect to the plane of its motion also changes, going from 22.1 degrees to 24.5 degrees and back in about 41,000 years; this is called the change in obliquity. And the direction of the Earth’s axis in space swings around in a circle in a complicated cycle that averages about 23,000 years – this is called precession. Since the mid-19th century, several scientists had pointed out that these changes should affect the amount of light that the Earth receives from the Sun – its insolation, as received sunlight is called – and this might explain why we have had Ice Ages in the past (a fact discovered only in 1840, by Louis Agassiz). The most sophisticated theory of climate change caused by astronomical cycles was proposed by James Croll in the 1860s and 1870s. But Croll's mathematical skills were not good enough to provide more than a general correlation with astronomical cycles.

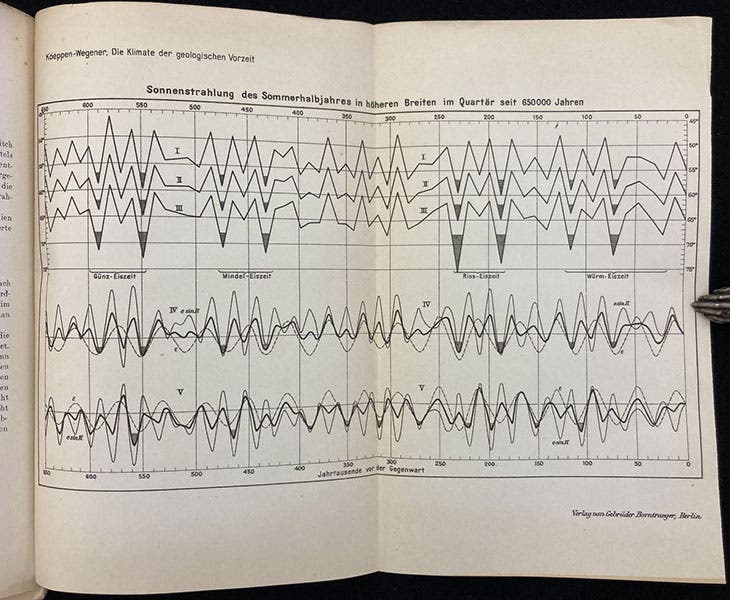

Milanković spent the War years calculating – the parameters of the Earth’s orbit interact and change in a very complex manner – but he found that he was able to demonstrate that at certain times in the past, summer temperatures in the northern hemisphere were significantly lower than normal. He found four such periods, and meanwhile geologists in Europe had identified four distinct glaciations (as geologists call ice ages), which they named Günz, Mindel, Riss, and Würm, from oldest to most recent. Milanković had in a sense predicted these four ages.

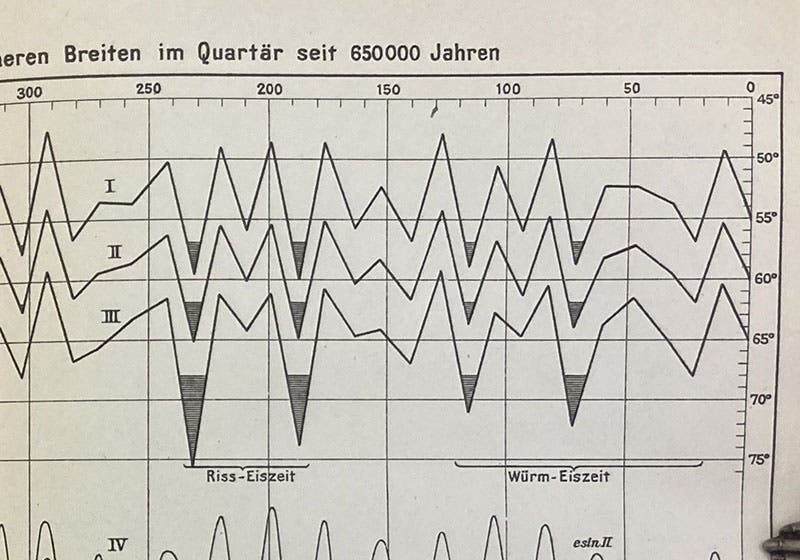

Milanković published a book of his own in 1920, which no one noticed. But his work came to the attention of Wladimir Köppen, a noted Russian-German climatologist who, with his son-in-law Alfred Wegener, was preparing a book on prehistoric climates, which was published in 1924. He included at the end a graph based on Milanković’s predictions, showing the four low points and correlating them with the four glaciations. We include the entire graph (fourth image), as well as a detail that shows two of the low-temperature predictions and the corresponding glaciations (fifth image). Milanković’s cycles now came to wider scholarly notice.

Milanković spent the rest of his life as a professor in Belgrade, and it was there, in 1941, that he published his Kanon der Erdbestrahlung und seine Anwendukng auf das Eiszeitenproblem (Canon of Insolation and the Ice-Age Problem, 1941). The war limited the distribution of this book, and those who did hear about Milankovitch cycles were generally unconvinced, so that when Milanković died in 1958, he was still relatively unknown, and his ideas were not yet accepted. But a 1976 paper by three modern paleoclimatologists, studying ice cores, rehabilitated Milanković and confirmed the impact of his cycles. The current opinion is that Milankovitch cycles do indeed play a major role in determining the Earth's climate. We do not have his Kanon in the Library, but we do have the 1924 book, Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit (The Climate of Ancient Geological Times, 1924), by Wladimir Köppen and Albert Wegener, which first announced Milankovitch cycles to the scientific community, and which was the source for our fourth and fifth images.

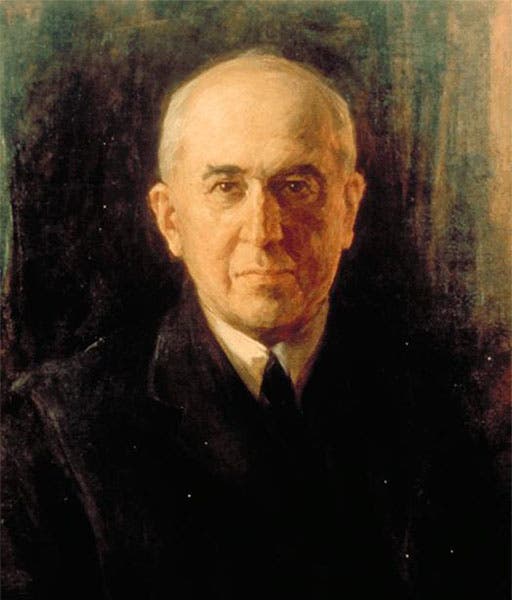

Milanković is one of the two great scientific heroes of modern Serbia (the other being Nikola Tesla), and he is featured on a 2019 Serbian postage stamp. We include two portraits here, one of Milanković as a student (first image), and another, a painting, showing the older professor (second image). The latter was used for the Serbian stamp. As you may have noticed, I also like statues, and I am pleased that there is a statue of Milanković in Belgrade (sixth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.