Scientist of the Day - Murray Gell-Mann

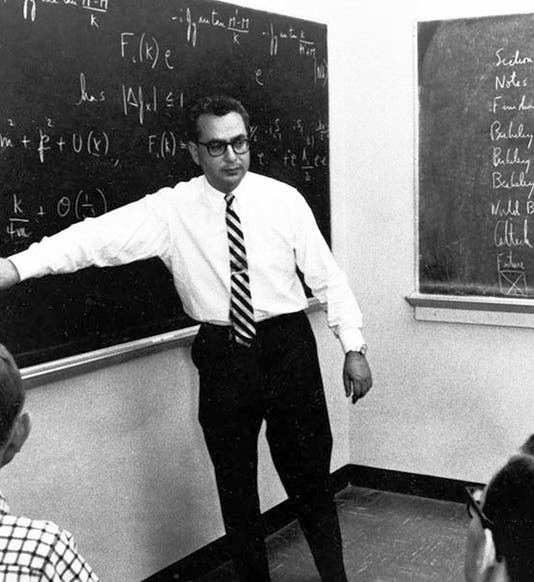

Murray Gell-Mann, an American physicist, died May 24, 2019, at age 89. Born in New York City to immigrant parents, he showed the precocity typical of people who later become physicists, graduating from high school at age 14 and attending Yale University. He wanted to major in archaeology or linguistics; his father insisted on a field where he could earn a living, such as engineering; they compromised on physics, a subject Gell-Mann was not fond of at the time. But it turned out to be right up his alley. He did well at Yale, and went on to do his graduate work at MIT under Victor Weisskopf. After teaching at several universities, he was appointed to the faculty at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), joining Richard Feynman, where he would teach and investigate subatomic particles for almost 40 years.

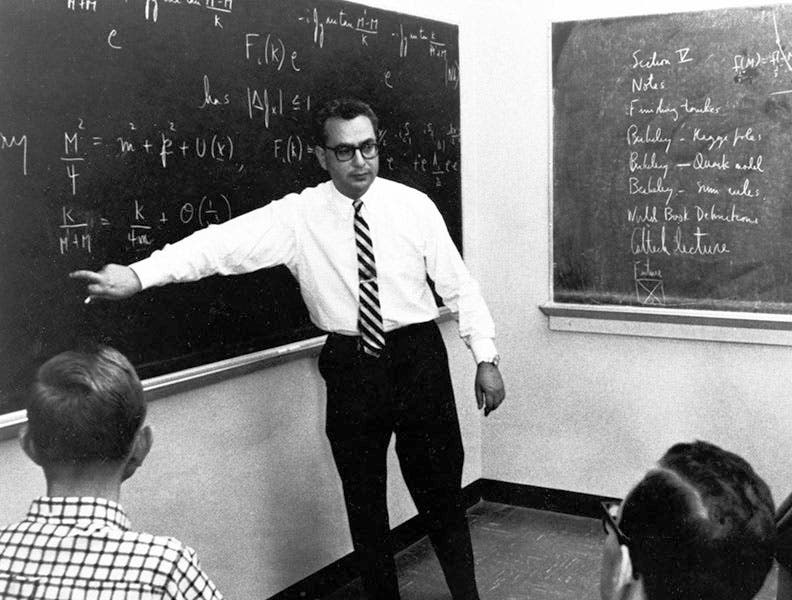

Particle physics was a mess in the late 1950s. The atom had been a tidy place in the 1940s, made of protons, electrons, neutrons, and photons, with neutrinos occasionally masking their presence known. But in a short period of time, a slew of new particles were discovered, most of them mesons, such as the pion and muon, as well as new kinds of neutrinos, and particles called bosons. Physicists often referred to the situation as the "particle zoo." It was Gell-Mann who brought order to the zoo by proposing, in 1963, that protons, neutrons, and mesons are not simple particles, but are built up of smaller particles called quarks (second image). Quarks, Gell-Mann suggested, come in three different “flavors,” which he named up, down, and strange, and the different quarks have fractional electric charges, like +2/3e or -1/3e, where e is the charge on the electron, thought (before Gell-Mann) to be the smallest possible electric charge. One up-quark and two down-quarks make a neutron; while two up-quarks and one down-quark make a proton. The strange quark is involved (with the up and down) in comprising the mesons. Quarks are always found in combination and never alone. Gell-Mann realized that he could account for almost all the particles in the zoo with his quarks, although, eventually, new quarks had to be postulated (there are now 6, with the addition of top, bottom, and charm).

Gell-Mann originally called his new particles "kworks," because he liked the sound of the word, but when he learned of a passage in James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake that reads: "Three quarks for Muster Mark!," he adopted Joyce as the patron of the quark, especially since Joyce’s quarks came in threes, and he immediately switched to Joyce's spelling (while keeping his own pronunciation of “kwork”). It was a good name. It is worth mentioning that quarks were proposed independently and simultaneously by George Zweig, who suggested four new elementary sub-particles, and called them "Aces". Quarks won by a landslide, and hardly anyone remembers Zweig's important role in the saga of quarks.

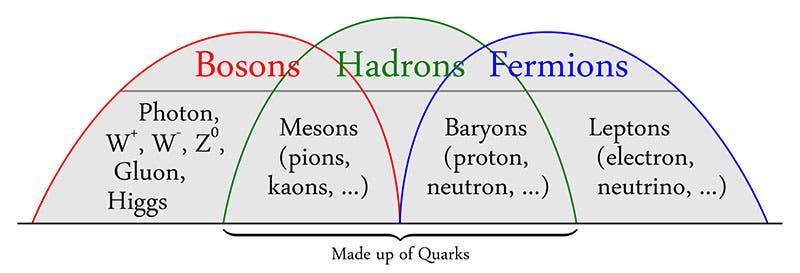

Gell-Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969 for his work in particle physics, although the word quark was not mentioned in the citation, which was: "for his contributions and discoveries concerning the classification of elementary particles and their interactions". Feynman later recommended to the Nobel committee that Gell-Mann and Zweig be awarded a Nobel Prize specifically for the discovery of quarks, but no action was ever taken. In the Nobel photo of 1969 (third image), where Gell-Mann is the second from left, there are 2 others who have been Scientists of the Day: Salvador Luria (2nd from right) and Max Delbrück (far left). In the post on Delbrück, there is a different photo showing all 5 Caltech scientists who have won Nobel Prizes, which includes Gell-Mann (second from left) and Richard Feynman (second from right).

After he retired from Caltech in 1993, Gell-Mann returned to his early interests in archaeology and the evolution of human languages. He had helped establish the Santa Fe Institute in 1984, a think tank of sorts intended to allow free discussion of all sorts of ideas, mainstream and fringe, and he joined the Institute resident faculty. The Institute is still going strong, and Gell-Mann died there in 2019. He was buried in Red Butte Cemetery in Aspen, Colorado.

The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Siimple and the Complex, by Murray Gell-Mann, W.H. Freeman and Co., 1994 (author’s copy)

In 1994, Gell-Mann published a book intended for a general audience, called The Quark and the Jaguar (it was rather hard to photograph properly, with its transparent mylar dust jacket, fifth image). It is mostly about the (then) new idea of complexity, and Gell-Mann resisted those who would bring mysticism into science. I read it when it first came out, 30 years ago, and I did not re-read it for this post, so all I remember is that I enjoyed it at the time. Thus I give it a qualified recommendation.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.