Scientist of the Day - Nicolas Lemery

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Nicolas Lemery, a French chemist, was born Nov. 17, 1645. Lemery was one of the first of what we call "mechanical chemists", who tried to explain chemical reactions by the interactions of small particles of different shapes and sizes. Lemery proposed, for example, that acids consisted of corpuscles with tiny points or spikes, while bases had little receptors for those spikes. So when you mixed the two, you produced a compound that was neither acidic nor basic, as the spikes of the acids meshed with the holes in the bases.

Lemery also offered up a mechanical theory of volcanic action. In 1700, he published the results of an experiment in which he buried iron filings and sulfur under a layer of earth, and then soaked the area with water. After a time, the temperature rose and the earth expanded, gushing forth hot fluids. Volcanologists were much taken with this theory for about a century, until it was shown to be inadequate.

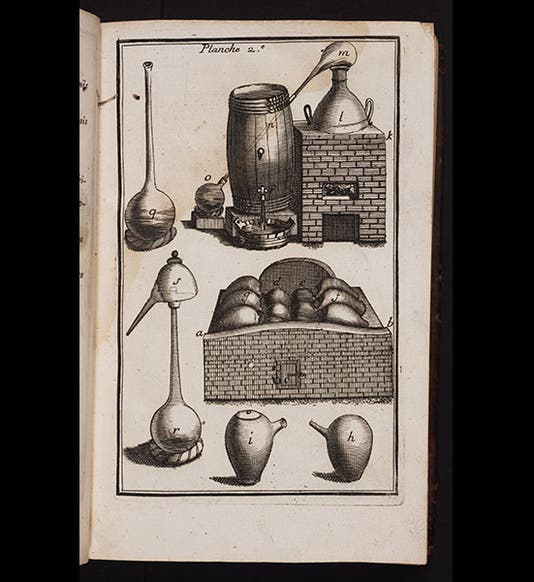

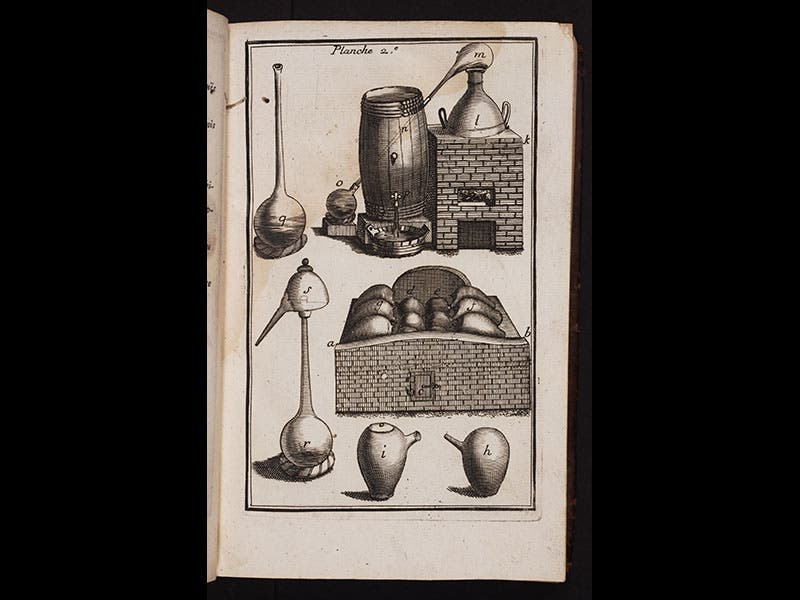

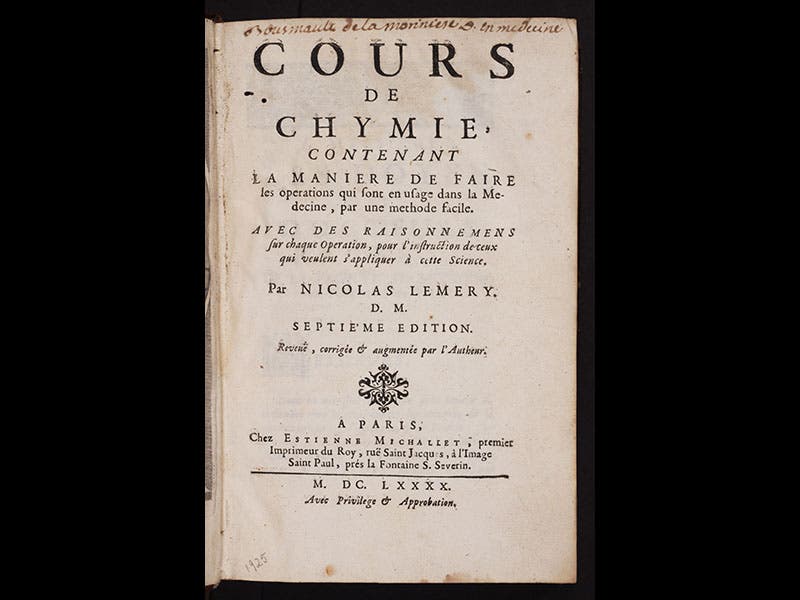

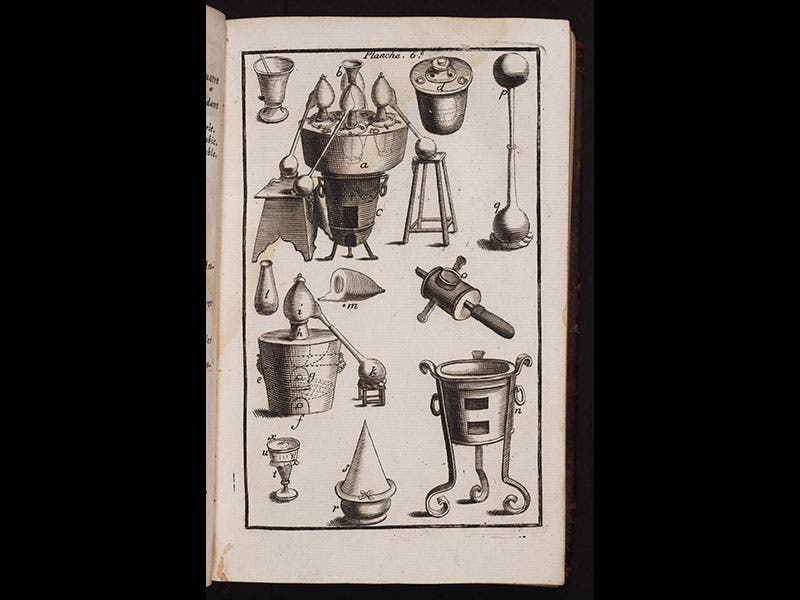

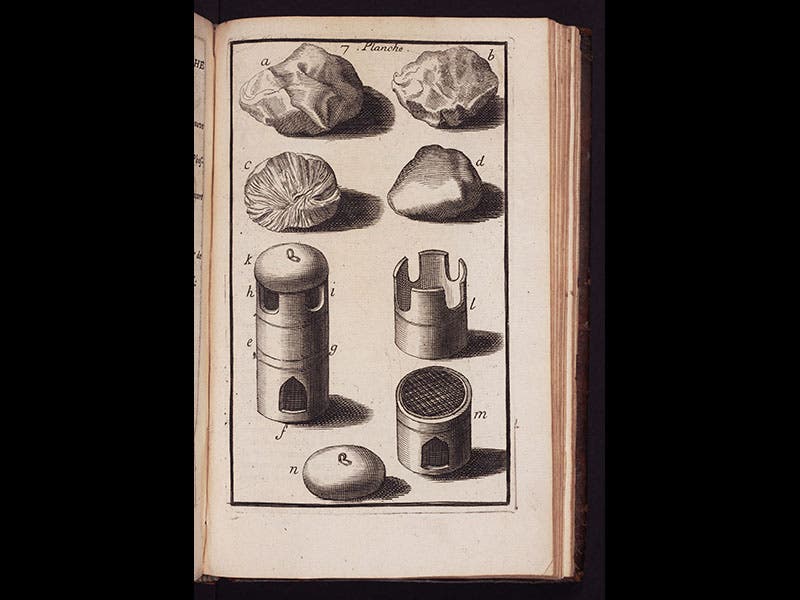

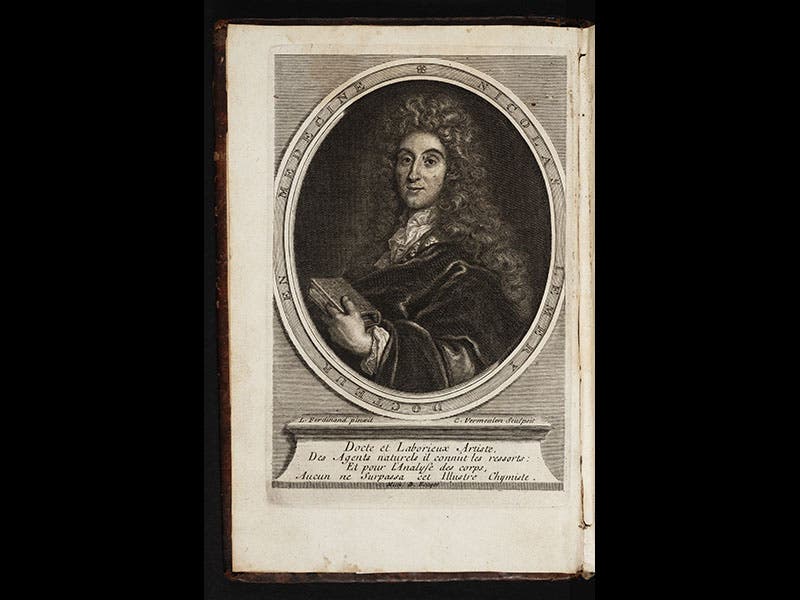

Lemery's textbook, Cours de Chymie (1675) was probably the most popular chemical manual in the world for the next 75 years, especially since Lemery’s chief English rival, Robert Boyle, never wrote such a text. We do not have the first edition in our collections, but we do have an edition of 1681, which is not illustrated, and the 1690 edition, which is. Not surprisingly, we chose the 1690 edition to highlight above, with its images of typical 17th-century chemical apparatus. This edition also has a frontispiece portrait of Lemery (sixth image).

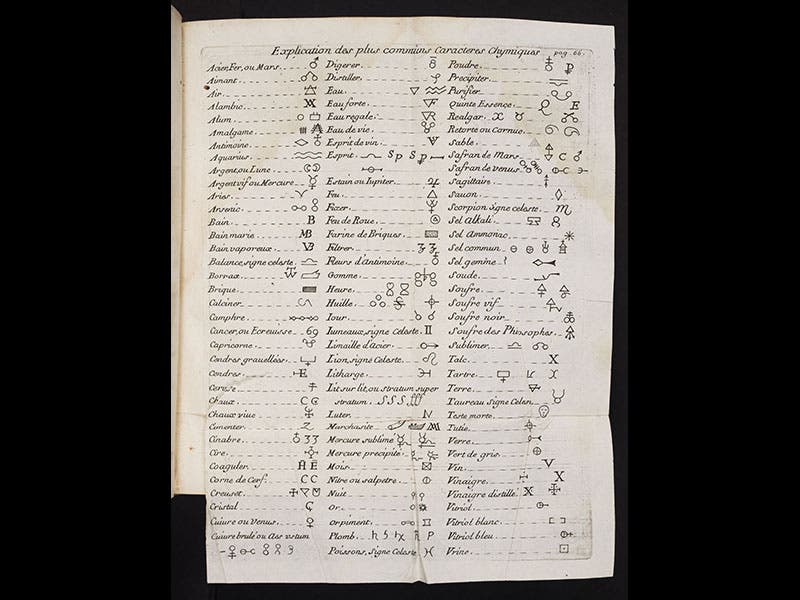

The last plate in the 1690 edition (fourth image) depicts the Bologna stone, those phosphorescent barite crystals that so fascinated 17th-century inquirers, including Galileo. Another plate (fifth image) depicts chemical terminology and symbols of Lemery’s day, reminding us why the nomenclature reform of Lavoisier, Guyton de Morveau and others a century later was so crucial to the chemical revolution.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.