Scientist of the Day - Scientific American

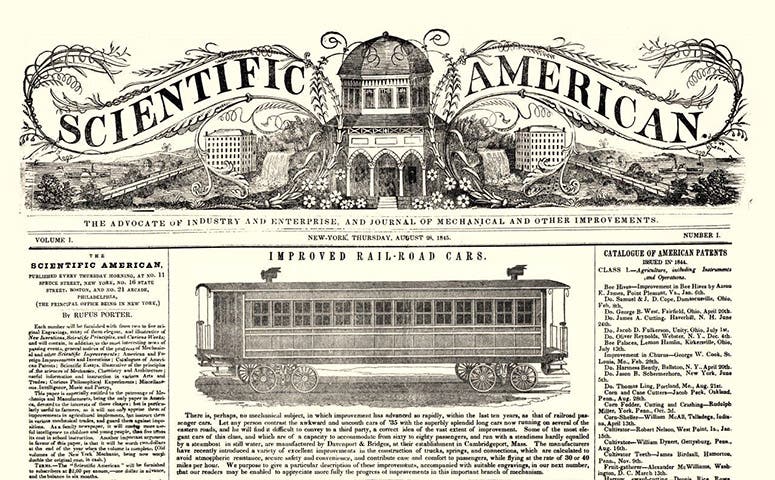

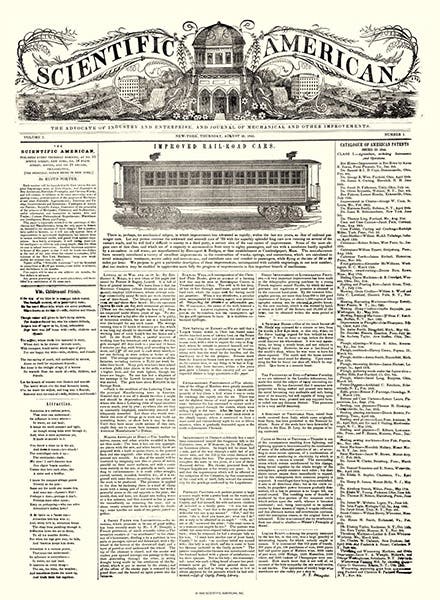

The very first issue of Scientific American magazine was published on Aug. 28, 1845, 180 years ago today. It was the brainchild and handiwork of Rufus Porter, an inventor from Maine then living in New York City. The intent was to showcase American inventions, manufacturing, and engineering, as well as agricultural innovation, as Porter explains in a box in the upper left of the front page of issue #1 (fourth image). I don’t know who designed the masthead graphic (first image), but it describes the proposed scope of the journal even better than Porter.

We have a nearly complete run of Scientific American, which came to us when we acquired the library of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1946. Unfortunately, that acquisition did not include volume 1, which had wandered off sometime before, so the images we show here are from Wikimedia commons. The first issue is also available from Scientific American as a pdf file.

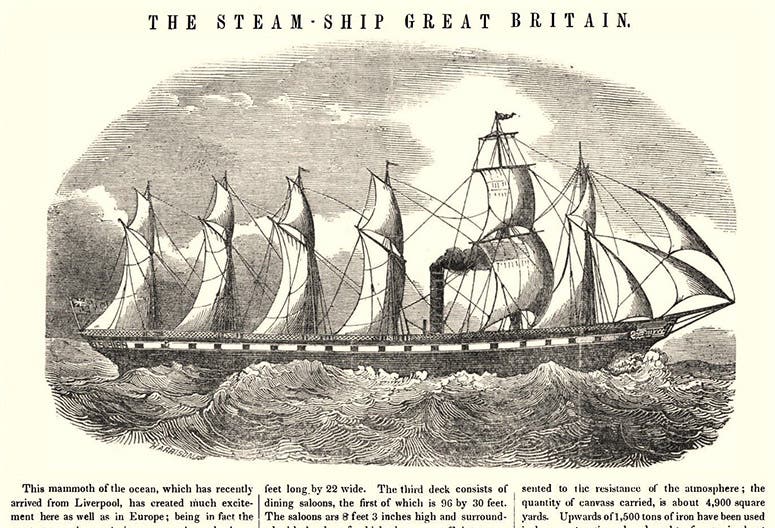

Right from the start, Porter boasted that each issue (of 4 pages) would contain 2 to 3 original engravings, and that became a hallmark of the magazine as it developed and flourished. If you want a large wood engraving to illustrate an article on the building of the Eads Bridge in St. Louis or the digging of the New York subway, the Scientific American archives is a smart place to look. I have included such images scores of times in this series, being especially fond of the front-page engravings, which are often full-page, some of which you can see in our posts on Alvan Clark, Charles Knight, and John A. Roebling.

Rufus Porter sold his new magazine after just 2 years at the helm, so most of the credit for the success of Scientific American goes to others. His successors did their jobs well. Scientific American is still being published 180 years after that first issue, making it America’s oldest continuously published scientific journal. I have been a subscriber for 60 years myself, which means I have one-third of the published issues sitting on shelves not far away. The heyday of the magazine was, in my opinion, in the 1960's and 1970s, when nearly every article was written by a distinguished scientist, and the articles were illustrated with striking photographs and some of the best informational graphics in the business. The journal now is different, with articles mostly by science journalists and editors and with graphics that are showy but often have no informational content at all. But I am probably out of touch with what one needs to do to flourish in the journal market today. The magazine has added one new feature that I really like, called "Meter," edited by Dava Sobel, that offers an original poem every month on a science-related subject. It is nice to see the arts and sciences talking to one another. Rufus Porter, a painter himself, would have appreciated this development.

One of my favorite pastimes, when I need inspiration, is to head into the stack section of the Library that holds the bound volumes of Scientific American, and pull off a volume from, say, 1885 and just leaf through it, marveling at the hundreds of inventions that never quite made it, and the few that did, and being especially impressed by the machinery of all sorts that was turned out by and for manufacturers. The issues in those days were 16 inches tall, so you need a library table to hold them when they are open. Invariably, I stumble on an illustration of an invention or an engineering project that I have not discussed in this forum. And then I am good to go, as soon as that inventor’s or engineer’s birthday rolls around. I discovered Ottmar Mergenthaler just that way.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.