Scientist of the Day - Seth Eastman

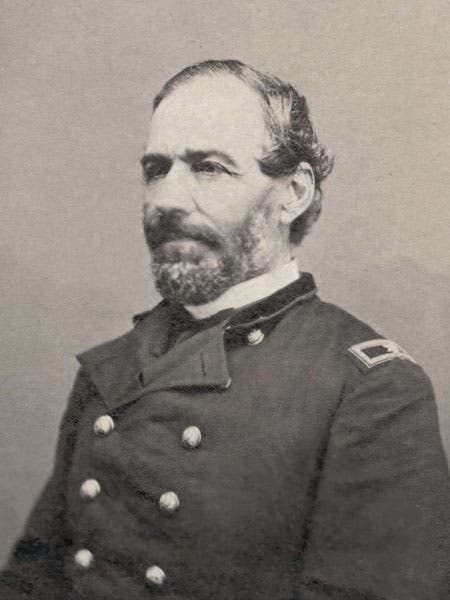

Seth Eastman, a U.S. Army military officer and an artist, died Aug. 31, 1875, at the age of 67. Eastman came from Brunswick, Maine, the eldest of 13 children, and won an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in 1824. He graduated in 1829 (just before Edgar Allen Poe arrived there) and headed out West, where he ended up at Fort Snelling on the Mississippi River in Minnesota. He began to record the culture of the Dakota peoples with his artist’s pen and brush, amassing a large collection of drawings and watercolors of native American life. He continued this activity during a second stint at Fort Snelling in the late 1840s, this time as Fort commander.

In 1846, Congress allocated funds for the compilation of a history of the Indian tribes of North America, and Henry Schoolcraft was given control of the project. Schoolcraft wanted the noted artist George Catlin to provide the illustrations for his book (which would swell to 6 volumes before it was completed) and even travelled to see Catlin and twist his arm, but Catlin turned him down. Eastman heard about the endeavor and applied for the job of book illustrator, and was turned down twice, but eventually, through the lobbying of his wife Mary Henderson, he secured the appointment. Over the next seven years, he provided 275 paintings of native Americans and their culture, illustrations that were turned into engravings or lithographs for Schoolcraft's book, which was published between 1851 and 1857. It had the kind of unwieldy title that government publications often bore even back then: Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, a set that we have in our collections.

We wrote a post on Schoolcraft earlier this year, in which we showed 5 of the prints made from Eastman’s paintings, 3 chromolithographs and 2 engravings, and expressed a desire to do a post on Eastman, so we could show more of his artwork. Today we are able to do just that. For the article on Schoolcraft, we drew on the first two volumes of Indian Tribes of the United States; today, we take our examples from volume 3.

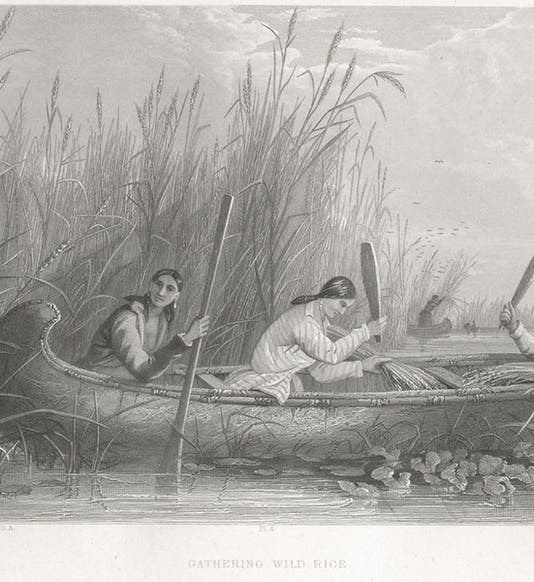

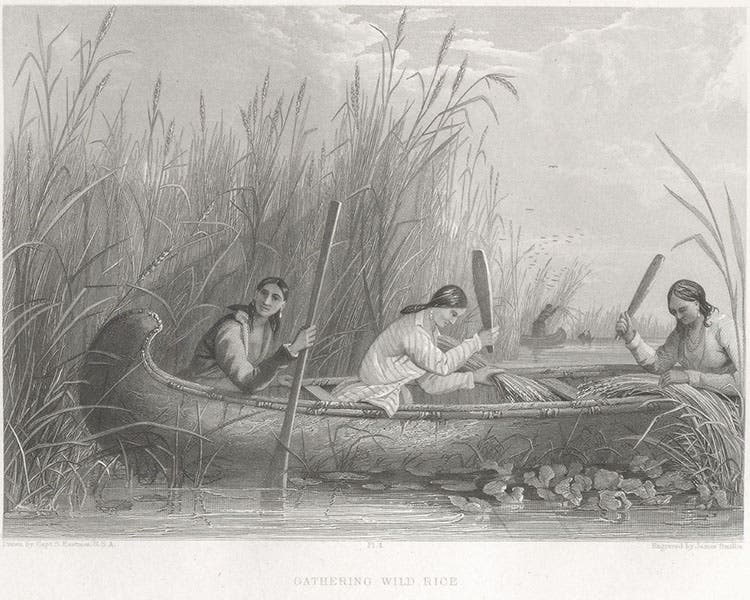

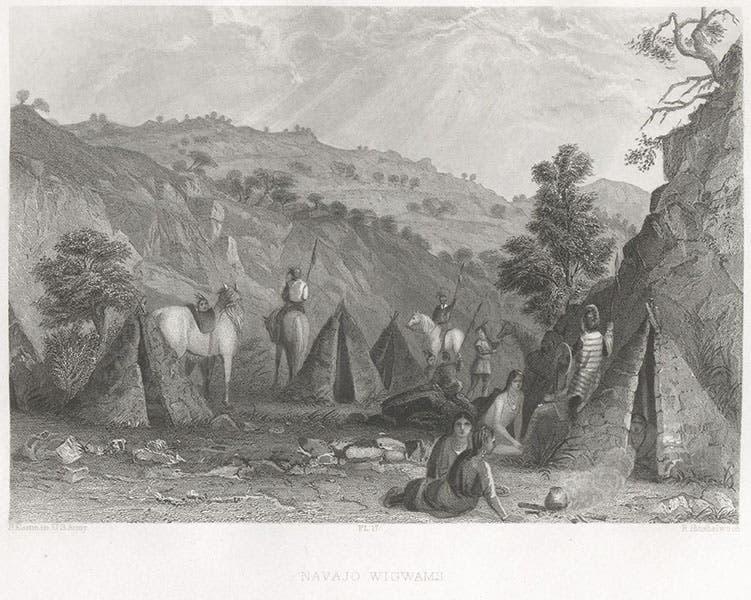

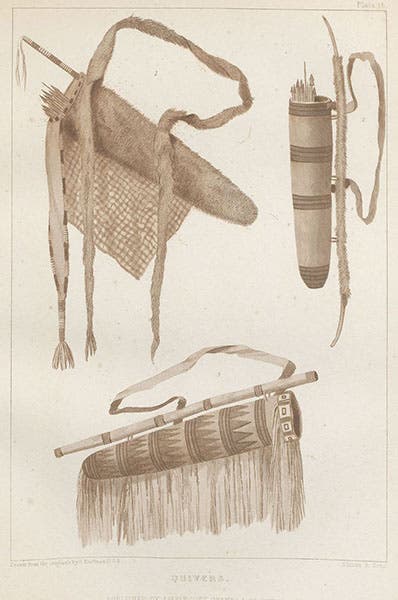

My favorite print in volume 3 is the one that leads us off, captioned “Gathering wild rice.” It shows Ojibwe women in a real birch-bark canoe, gathering grain by shaking the stalks over the canoe. Other prints we chose depict attempts to scare crows from a cornfield (third image), and an encampment of Navajo wigwams (fourth image). We include a detail of the latter so you can see Eastman’s signature, at the bottom left of each engraving (fifth image). There are also a number of plates in the volumes that depict native American cultural objects, such as headdresses and warclubs; we show one that illustrates three kinds of Indian quivers (sixth image).

Much of Eastman’s original artwork survives. The Minneapolis Institute of Art has 35 Eastman paintings and drawings, including the original watercolor for Schoolcraft’s print of Indians gathering wild rice (seventh image). The Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth has an Eastman painting called Dakota Playing Ball on the St. Peter’s River, which was the basis for another Schoolcraft illustration, which we included in our post on Schoolcraft, as the 7th and last image there.

After his retirement following the Civil War, Eastman was recommissioned so that he might fulfill two requests from Congress: a series of 9 new paintings of Indian life, to be displayed in the Capitol Building, and a set of 17 paintings of prominent U.S. forts, also for public display in the Capitol. I do not know what happened to the Congressional Indian paintings, but the paintings of forts are still there, at least the ones on the Senate side. You can see thumbnails of all 8 Senate paintings at this link. We include Eastman’s painting of West Point (ninth image), not so much for the quality of the painting, but because he was working on it when he died, on this day in 1875.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Andromeda and Perseus, constellations figured by James Thornhill, with star positions determined by John Flamsteed, in Atlas coelestis, plate [15], 1729 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1b30cfec-5be6-4297-a7fb-97255ba992e5/thornhill1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)