Scientist of the Day - Theodor Galle

Theodor Galle, a Flemish engraver, was born or baptized on July 16, 1571, in Antwerp. His father, Philips, was a publisher and engraver, and he taught engraving skills to his son. We have one book in our library engraved by Theodor (also known as Theodoor, Theodore, and, oddly, Dirck), and it is an unsung wonder of a portrait book. I have become very conscious, and appreciative, of Renaissance and early modern portrait books, ever since I began this Scientist of the Day series, as I always like to show a portrait of my subject, and in the period before 1700, this can sometimes be difficult. For ancient scientists, it is often impossible. Fortunately, between about 1570 and 1700, there were at least nine published collections of engraved portraits of famous persons, of which we have seven in our collections at the library. I have written posts on two of these compilers: Charles Perrault, including 6 of his portraits of scientists (by a variety of artists and engravers, 1696), and Theodor de Bry, who engraved the portraits in a compilation by Jean-Jacques Boissard (1597-99); you can see six of de Bry’s engravings at the link.

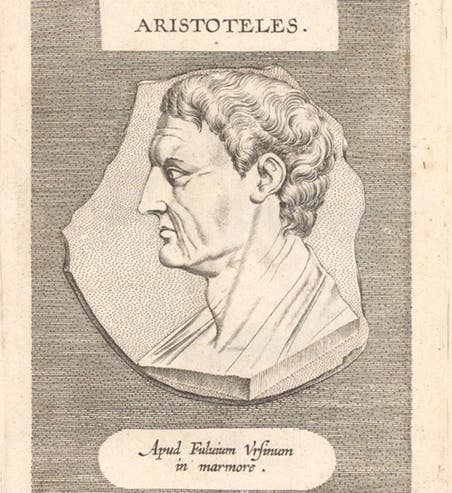

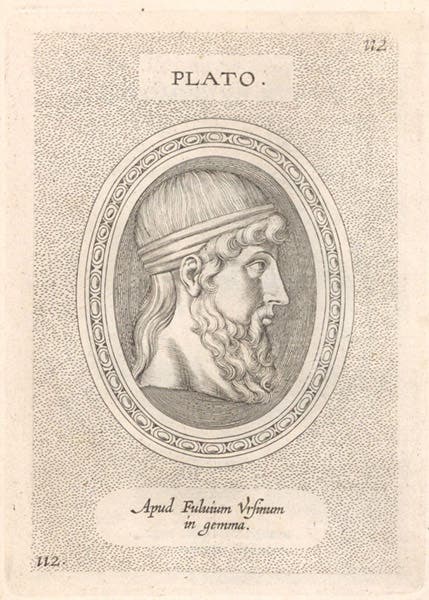

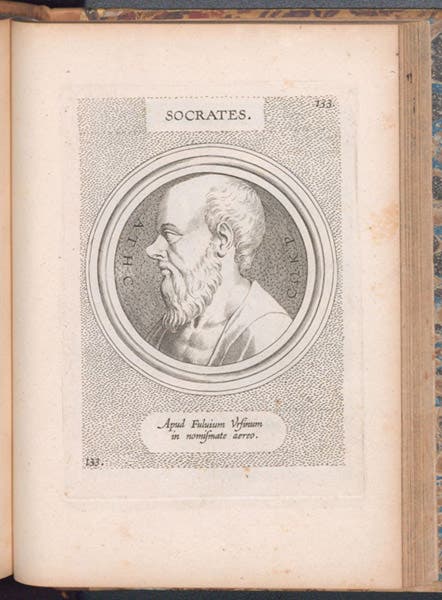

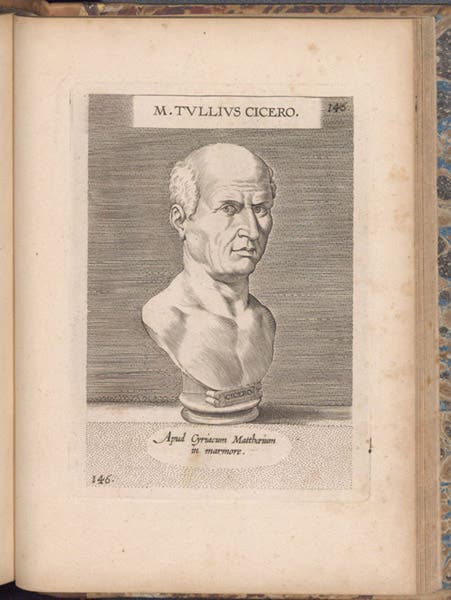

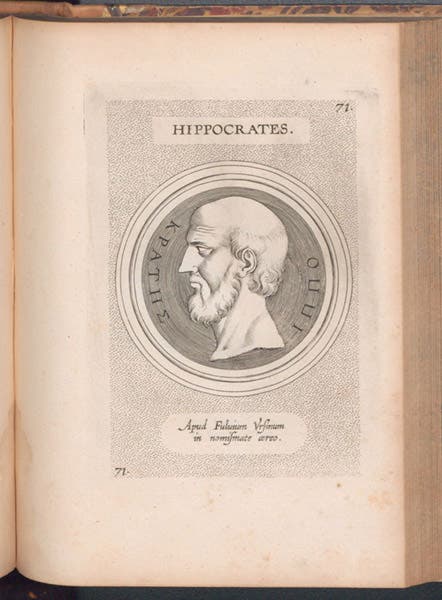

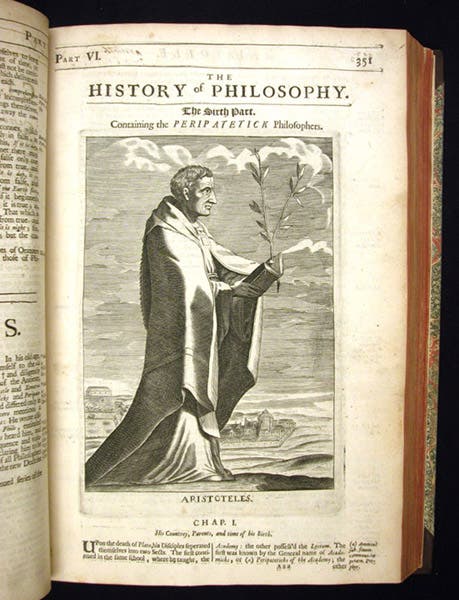

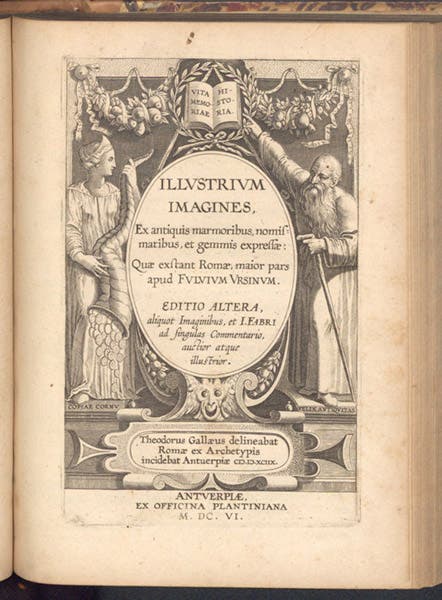

But the portrait book of Theodor Galle stands out because it contains 178 engraved portraits, not of contemporaries, but of distinguished ancient Greeks and Romans, of whom a good number are natural philosophers or mathematicians. It was called: llustrium imagines, ex antiquis marmoribus, nomismatibus, et gemmis expressæ : quæ exstant Romæ, maior pars apud Fvlvivm Vrsinvm (Images of the illustrious, from ancient marbles, coins, and gems, as they exist in Rome, most in the collection of Fulvio Orsini, 1606). We have only one other work that depicts ancient scientists, and that is Thomas Stanley's History of Philosophy (1687), upon which we have drawn several times, for example, in our posts on Pythagoras (first image at the link) and Democritus (last 2 images at the link). But the portraits there, with several exceptions, were not based on anything except the artist’s imagination. That contrasts strongly with Galle's portfolio of portraits, which were drawn from a collection of ancient cameos, statuary, and reliefs assembled by Fulvio Orsini in Rome. Orsini, before his death in 1598, prevailed on Johann Faber to describe his collection of portraits, and Galle to engrave them. The work of both men was printed in 1598 (an edition I have never seen) and then again in 1606 (our edition).

We include five of Galle’s portraits in our post today, including those of Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, Cicero (more of a natural philosopher than you might think), and Hippocrates. Of course, just because they were drawn from Greek and Roman antiquities does not mean they are true portraits, only that there was a carved image in Rome in 1600 that had a famous name inscribed next to it.

The portrait of Aristotle (first image) was a little different. For whatever reason, Galle’s depiction of the Stagirite was accorded a veracity that was not granted to most of the other portraits. Galle's engraving of Aristotle, showing him in profile, as relatively young and beardless, with short curls and a distinctive Greek nose, was copied for a number of engraved title pages in the later 17th century, so that often you can recognize Aristotle, even in the absence of a caption. For example, Galle’s portrait was clearly the source for the depiction of Aristotle in the frontispiece to Richard Waller's translation of the Saggi (Essays) of the Cimento Academy (1684), which we reproduced as the first image in our post on Waller (Aristotle is at far left, and was identified by a label on the hemline of his garment).

In a post on Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek two years ago, we showed, as our fifth image, a title-page engraving of 1692 that included a portrait of Aristotle at far left center; again, it was clearly drawn from Galle’s portrait, although he is not identified by name. Indeed, the depiction of Plato, with the headband, just to the right of Aristotle (also not captioned), was taken from Galle as well.

We mentioned that most of Thomas Stanley’s portraits of ancient philosophers were merely the products of artistic license. Not so his portrait of Aristotle, which we show here (seventh image). It is not a great portrait, because the body is hunched over. But the face in profile is perfectly fine, because it was copied (in reverse) from Galle.

I do not know why Galle’s collection of portraits is such a secret – it is not all that scarce. But there is no portrait taken from Galle’s book anywhere on Wikipedia (as best I can determine), and hardly anywhere else on the Web. Galle’s portrait collection deserves to be better known, and more widely used.

The Illustrium imagines has a handsome engraved title page, also sculpted by Galle. I see no reason not to include it here (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.