Scientist of the Day - USS Niagara

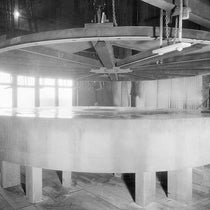

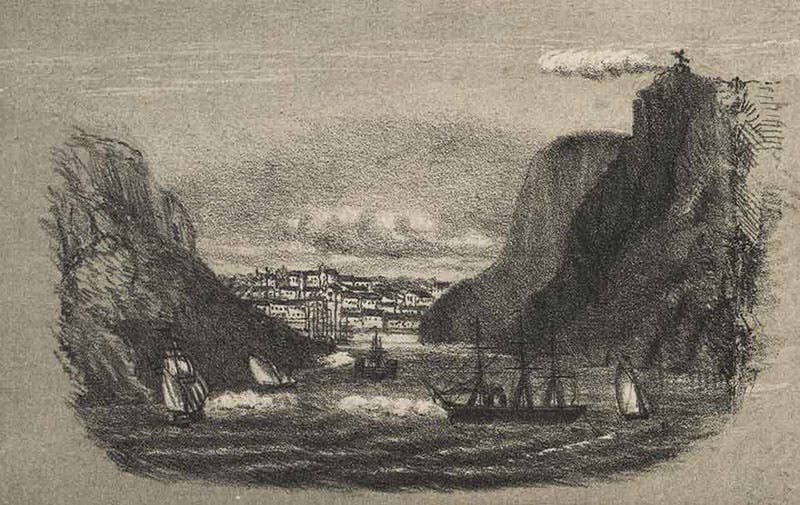

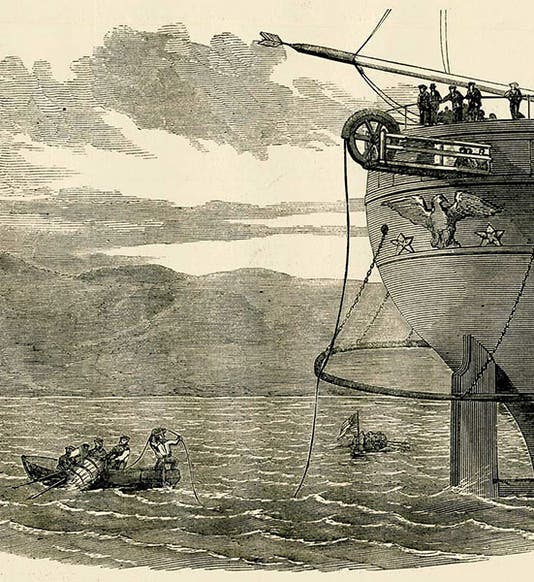

In the wee morning hours of Aug. 5, 1858, the U. S. Steamship Niagara wended her way carefully into Trinity Bay on the eastern tip of Newfoundland, paying out a submarine cable as she did so. Cyrus Field, the man in charge on board the Niagara, was anxious to get the free end of the cable into the hands of the telegraph master in the new Telegraph House at Bay Bulls Arm, on the other side of the bay from the village of Heart’s Content. On the very same morning, HMS Agamemnon was carrying the other end of the very same cable into Valentia Harbor on the western tip of Ireland, which would soon be connected to Newfoundland by 2000 miles of fine woven copper wire surrounded by an insulation of gutta percha.

The USS Niagara entering Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, with the western end of the first Atlantic Cable, Aug. 5, 1858, detail of a tinted lithograph in Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore, by John R. Isaac, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

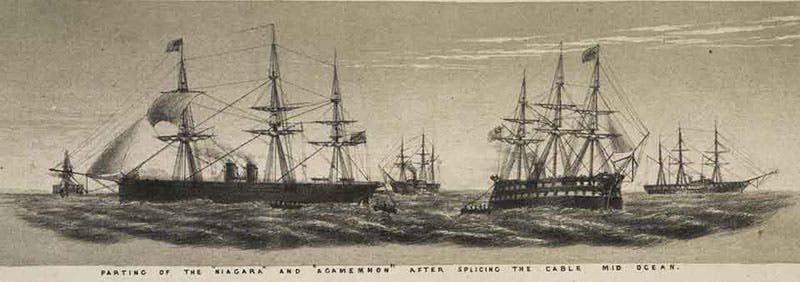

The two ships had started in mid-Atlantic 7 days earlier, each with a belly full of coiled wire cable. The mid-ocean ends were spliced together, and the two ships steamed off in opposite directions. They had tried this three times before that same summer, and once the previous year, but snapped cables stopped them. This time, the cables held together. Later that morning, some Morse code dots and dashes arrived from Ireland. The Atlantic Ocean had been electrically bridged.

It took another 10 days before a message was sent from Queen Victoria to President Buchanan, congratulating the American entrepreneurs who pulled this off, and for Buchanan to reply. With that, New York City went crazy. New York was the ultimate terminus of the first Atlantic cable, and their joy at being now joined, almost instantaneously, to London, knew no bounds. The city planned an exended celebration of parades and fireworks for the first 3 days of September, although in fact the festivities had begun two weeks earlier, with the arrival of the Niagara and her crew in the Port of New York, and the receipt of the Queen’s trans-Atlantic message.

We have a book in our collections that illustrates primarily the 1858 activities in Valentina Bay in Ireland, which the author, John Isaacs, witnessed and drew in person. But he did include a lithograph that illustrates, on one plate, the splicing of the cable in mid-Atlantic, and the landing of the shore cables in Newfoundland and Ireland. We show two enlarged images from that plate here (second and fifth images).

USS Niagara (left) and HMS Agamemnon, just after splicing their two cables in mid-Atlantic and heading for Newfoundland and Ireland, late July, 1858, detail of a tinted lithograph in Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore, by John R. Isaac, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

We do not have the book that shows the New York City celebrations in colored lithographs (sixth and seventh images). Fortunately, many are reproduced on a superb website, Atlantic-Cable.com, and we borrowed several for this occasion.

Unfortunately, by October, the cable was working only fitfully, and on Oct. 20, it was shut down and declared a failure. There were many recriminations all around, with principal blame assigned to the electrician, Wildman Whitehouse, who zapped the cable once too often with high-voltage coils. Fortunately, in 1866, a sturdier cable was laid, and this one not only worked, it kept working. But it never generated the excitement felt in the month following the first landing of the first cable, on Aug. 5, 1858.

We have written quite a few posts about the various actors involved in the two cable-laying attempts, including pieces on the mastermind, Cyrus Field; the original electrician Wildman Whitehouse; the replacement, William Thomson; the cable manufacturer, Geoge Elliot; Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who built the ship, the Great Eastern, that laid the successful cables, and William Howard Russell, who published an illustrated book on the venture of 1865-66.

And I do encourage you to take a look at the definitive website on the Atlantic cable enterprise, atlantic-cable.com. The website is old-fashioned and has no bells and whistles, thankfully, but it has something else missing from many more glitzy websites, consistently accurate information. And the authors have found and reproduced images and texts that I did not imagine existed and made them available to everyone. They have my deepest respect and appreciation for their efforts.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

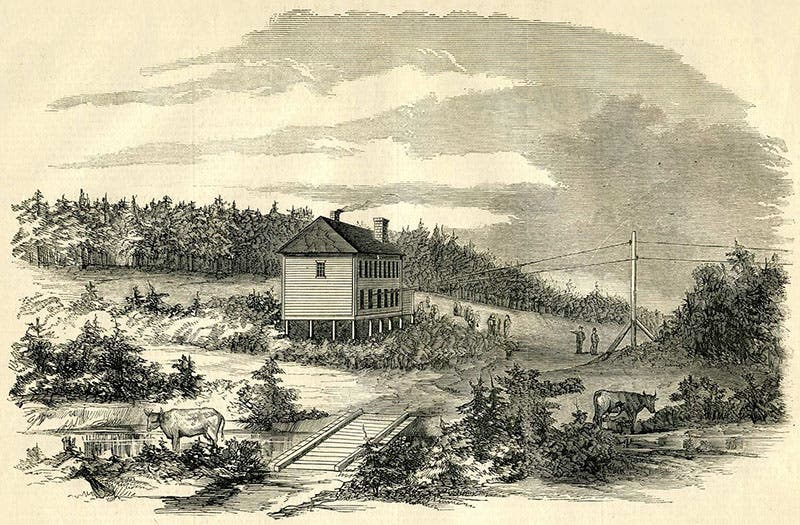

![Pulling the cable ashore, Aug. 4, 1858, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, with lithographs by Sarony, Major & Knapp, [1861], reproduced on atlantic-cable.com (atlantic-cable.com)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a2595e89-f876-4d7d-9e34-3d7679ba40c2/Niagara%203.jpg?w=800&h=517&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![A portion of unused cable taking part in the New York City parade celebrating the completion of the first Atlantic Cable, Sep. 1, 1858, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, with lithographs by Sarony, Major & Knapp, [1861], reproduced on atlantic-cable.com (atlantic-cable.com)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/ae8a241e-3616-4dc7-a987-4aab5b2e78e3/Niagara%206.jpg?w=800&h=513&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Firemen participating in the New York City parade celebrating the completion of the first Atlantic Cable, Sep. 1, 1858, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, with lithographs by Sarony, Major & Knapp, [1861], reproduced on atlantic-cable.com (atlantic-cable.com)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/fae2d04a-458f-409c-ac4b-cddceb5a1216/Niagara%207.jpg?w=800&h=525&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)