Scientist of the Day - William Benjamin Carpenter

William Benjamin Carpenter, an English physiologist and invertebrate zoologist, was born Oct. 29, 1813, in Exeter, making him 4 years younger than Charles Darwin, and 12 years older than Thomas Henry Huxley. Carpenter was the son of a Unitarian minister, a faith he would adopt, which cut him off from an Oxford or Cambridge education. Fortunately, the nondenominational University of London had been founded, and young Carpenter began his higher education there. He soon moved on to the University of Edinburgh, where he studied physiology, both comparative and human, and his first two books were on those subjects.

When Darwin was at Edinburgh, he was introduced to invertebrate zoology by Robert Grant. But Grant moved to the University of London in 1827, and I am guessing that Carpenter encountered him there, before heading to Edinburgh. The study of invertebrates, especially those of the deep sea, would later become Carpenter's special passion.

Carpenter was lecturer on physiology at the Royal Institution for 4 years, but he spent the bulk of his career as Registrar at University College London.

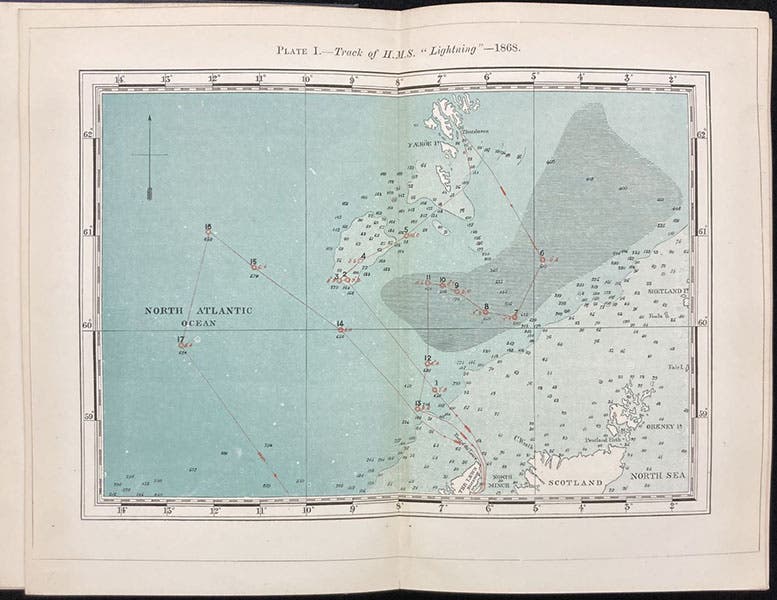

We are going to discuss today Carpenter’s participation in three cruises, 1868-70, in HMS Lightning and Porcupine. These were oceanographic voyages at a time when oceanography was in its infancy. The purpose was to drop dredges into the deep sea to see if there was life down there, below 500 fathoms. Scottish zoologist Edward Forbes, with his “azoic hypothesis”, had maintained there was not. Now that deep-sea dredges were available, it was time to verify or reject that hypothesis.

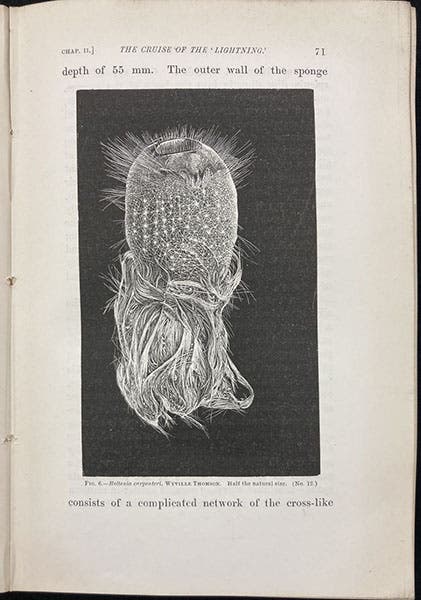

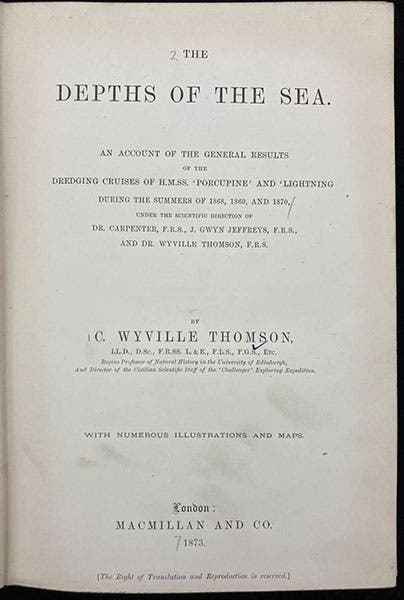

Three eminent invertebrate zoologists were involved – Carpenter, Charles Wyville Thomson, and John Gwyn Jeffreys. They explored north of Scotland (1868), west of Ireland (1869), and west of Spain (1870). Wyville Thomson wrote the very engaging and attractive book about their adventures and discoveries, The Depths of the Sea (1873), but took more than his share of the credit. I certainly gave him too much when I wrote a post on Wyville Thomson years ago. Today we stir a healthy portion of Carpenter into the mix.

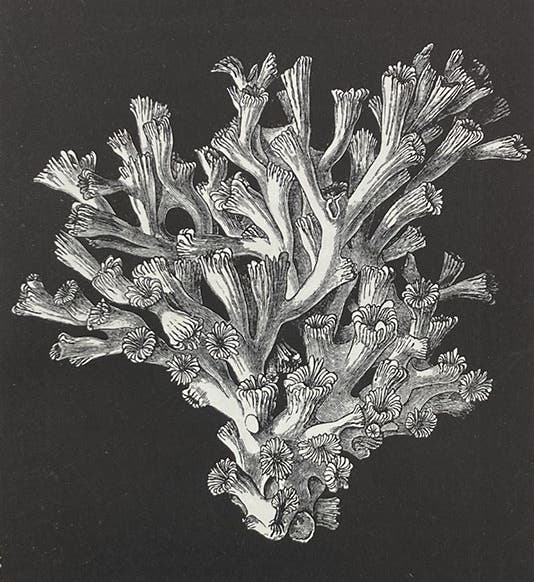

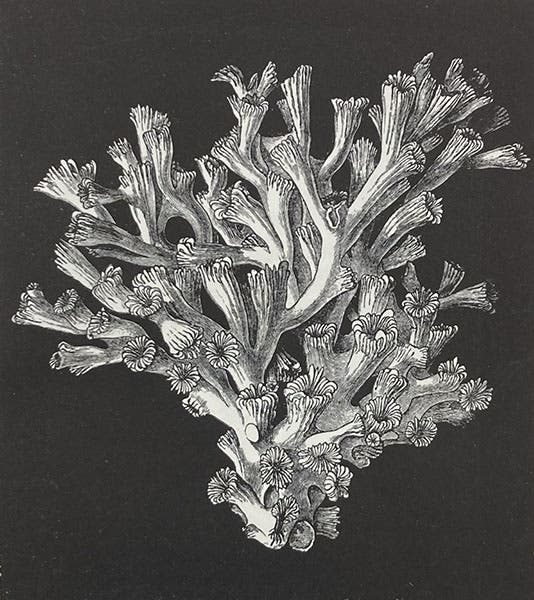

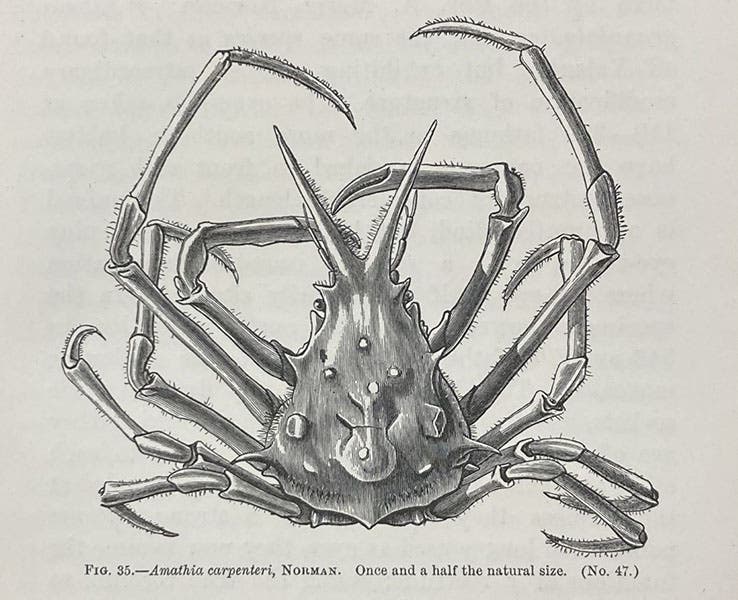

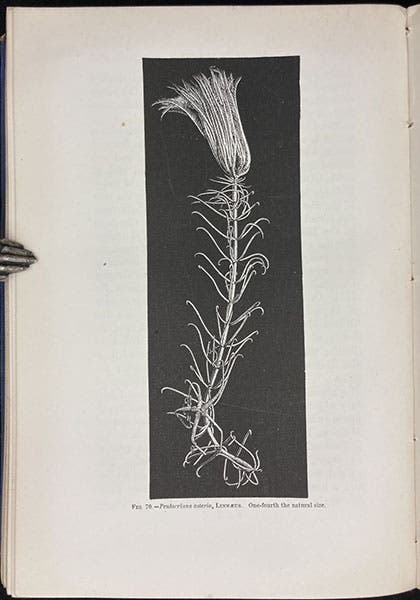

In a nutshell, the three men found a wealth of life in the deep sea, much of it quite strange. Since nearly everything they pulled up was new, it all had to be named and described. Several species were named after Carpenter, two of which I show here. Carpenter discovered many more, which were named after others, since naming your own discoveries after yourself is frowned on.

Title page, The Depths of the Sea: An Account of the general results of the dredging cruises of H.M.S.S. 'Porcupine' and 'Lightning' during the summers of 1868, 1869 and 1870 under the scientific direction of Dr. Carpenter J. Gwyn Jeffreys and Dr. Wyville Thomson, by Charles Wyville Thomson, 1873 (Linda Hall Library)

The three local oceanographic cruises were so successful that Carpenter urged the government to sponsor a more extensive oceanographic voyage that would circumnavigate the Earth and search for new life-forms in all of the Seven Seas. The result was the voyage of the Challenger (1872-76), which we wrote about several years ago, and where we also discussed the “azoic hypothesis” in more detail (and also promised to write a post on Carpenter). Carpenter did not go on the Challenger expedition, although I believe he wanted to, as he was deemed too old, at age 59.

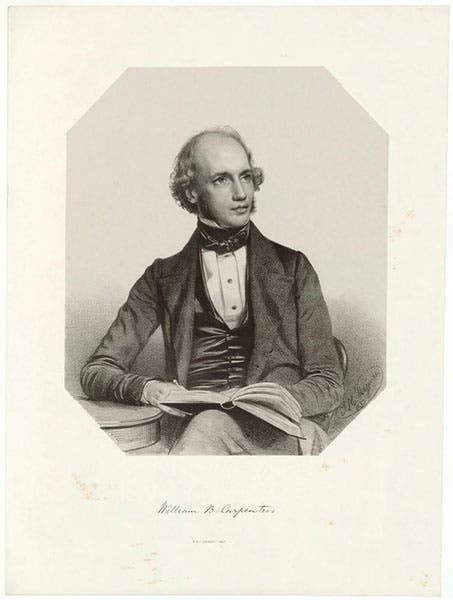

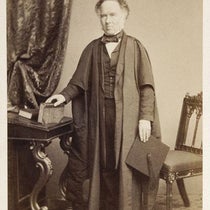

Most of the portraits of Carpenter one sees depict an older bewhiskered man, which he was on the Porcupine. But I prefer the lithograph portrait drawn by Thomas Maguire in 1850 (second image). I like it because Maguire, around the same time, drew Darwin, Grant, Joseph Dalton Hooker, Henry de La Beche, Richard Owen, all of which you can see at our posts on these gentlemen, plus about 50 more! It is an incomparable visual record of an especially gifted generation of scientists.

Carpenter died on Nov. 19, 1885, and was buried in Highgate Cemetery in North London, where you can also find the grave of Robert Grant.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.