Scientist of the Day - William Le Baron Jenney

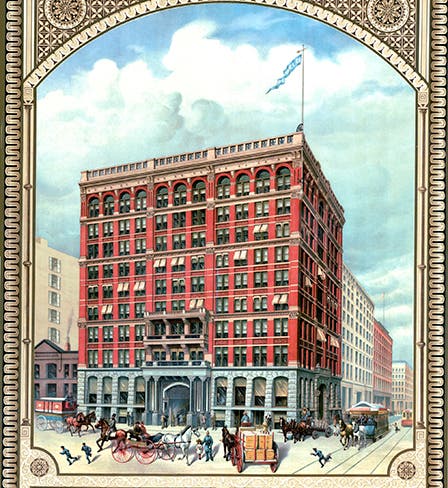

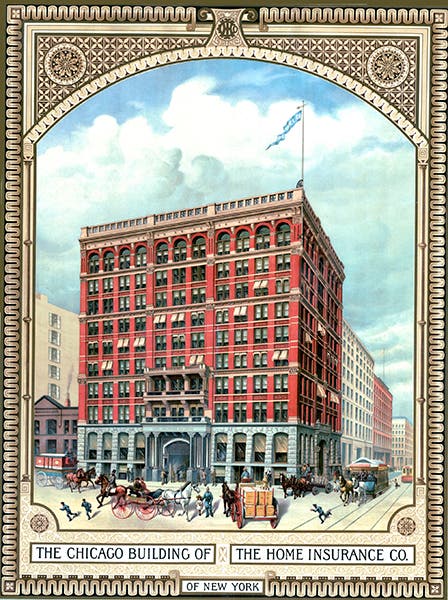

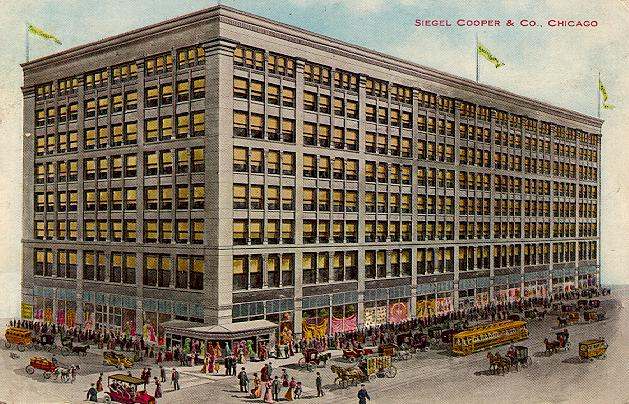

William Le Baron Jenney, an American structural engineer and architect, was born Sep. 25, 1832. Trained as a civil engineer at Harvard and in Paris, Jenney moved to Chicago in 1867, weathered the great Fire of 1871, and in 1885, he completed his most famous building: the Home Insurance Company Building in Chicago, which is often called, perhaps inappropriately, the first skyscraper (first image). The building was 10 stories high (180 feet) and had an iron skeleton with steel floor beams that carried much of the load; the masonry served to fireproof the metal frame and carry the remaining load. It wasn't quite the 100% load-bearing steel skeleton that would soon evolve, but it surely made the modern skyscraper possible.

Traditional building practices since time immemorial had used walls to carry the load of a building. This limits the height to which one can build, since even if the walls are masonry, they have to thicken at the bottom as the building gets taller, until soon you lose too much usable space at ground level. A steel skeleton is much stronger, and you can just hang the walls from the frame like curtains, and make them mostly of glass, if you want.

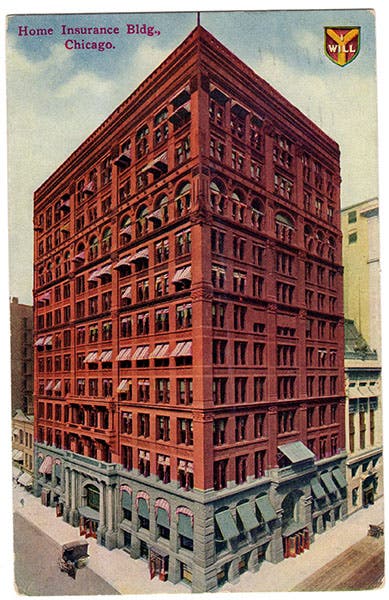

A two-story addition was added to the Home Insurance Company Building in 1891 (third image); if you compare it to a photo of the original building (first image), will see that the added stories didn't do much to improve the overall proportions of the structure. Still, this was a landmark building, and there was absolutely no excuse for tearing it down, which is what Chicago authorities allowed in 1931. If you want to see America's first skyscraper, or precursor, you are out of luck.

Jenney then designed what is sometimes called the Second Leiter Building, or Leiter 2 (1891), on South State Street in Chicago (fourth image). This is hardly a skyscraper, being only 8 stories tall, but in length it covers a full city block, and it has many of the features of a “Chicago School” building: a full load-bearing frame of structural steel, minimal ornamentation on the façades, and lots of windows. Leiter 2 changed hands several times and was eventually bought by Sears, Roebuck to be their main downtown department store. When Sears moved out in the 1980s, engineering groups lobbied to preserve it and prevent Chicago, to paraphrase Aristotle, from sinning twice against architecture, and Leiter 2 was eventually named a Chicago Landmark (and also a U.S. National Historic Landmark). So it is still there, the oldest steel-frame building surviving in the United States, or close to it.

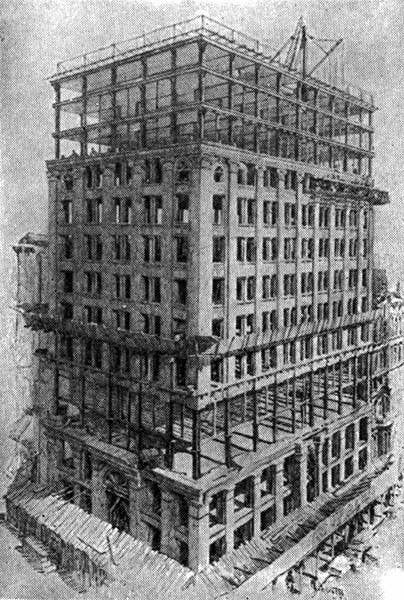

Jenney’s New York Life Insurance Building in Chicago, with 12 stories, was completed in 1894; a photo of the building under construction reveals the steel framework (fifth image).

There seems to be some disagreement as to whether Jenney, a supreme engineer, deserves the title of architect – one of his mentorees, the great Louis Sullivan, didn't think so. I asked my architect friend John Gillis (who guest-wrote our post on Sullivan), about this, and he was happy to award the title of architect to Jenney, but he pointed out that Jenney’s buildings never provided any visual evidence of the revolution he was helping to bring about. His decoration remained neo-classical throughout his career, and his buildings never seemed to emphasize their potential for growing taller and taller, which of course is what the steel frame makes possible. Sullivan did recognize what was happening, and his first skyscraper, the Wainwright Building in St. Louis (sixth image), inhabits a different world from Jenney’s, a world where buildings are going to grow and keep growing, and look like they are ready to do so.

There has been a lot of scholarly activity recently, attempting to take the title of “first skyscraper” away from the Home Insurance Company Building, arguing that it contained load-bearing masonry walls, very little steel, and that Jenney concocted the entire “first skyscraper” myth in 1896, in response to a journalistic inquiry; here is one such blog, which is moderately convincing to a non-expert like me. But either way, Jenney keeps his reputation as an innovative architect who recognized that steel-frame construction was going to radically change the way we design and erect buildings in our cities.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.