Scientist of the Day - William Sturgeon

William Sturgeon, an English electromagnetic experimenter, was born May 22, 1783, in Whittington, Lancashire. Every now and then, in preparing to write these daily anniversaries, I discover someone I have never of, who absolutely deserves to be well known, but who somehow has slipped through the historical cracks. Such a man is Sturgeon. He invented the electromagnet, for heaven's sake, the second basic step in founding the field of electromagnetism. The first step had been taken by Hans Christian Oersted, who discovered in 1820 that an electrical current flowing through a wire will deflect the needle of a magnetic compass. Everyone knows Oersted – why is Sturgeon often just a footnote? Let's see if we can figure that out.

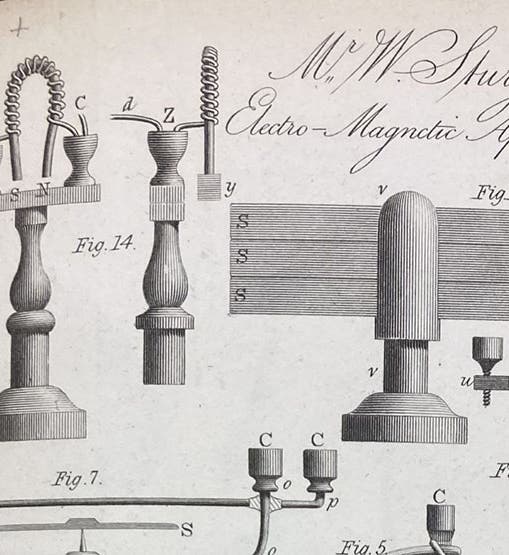

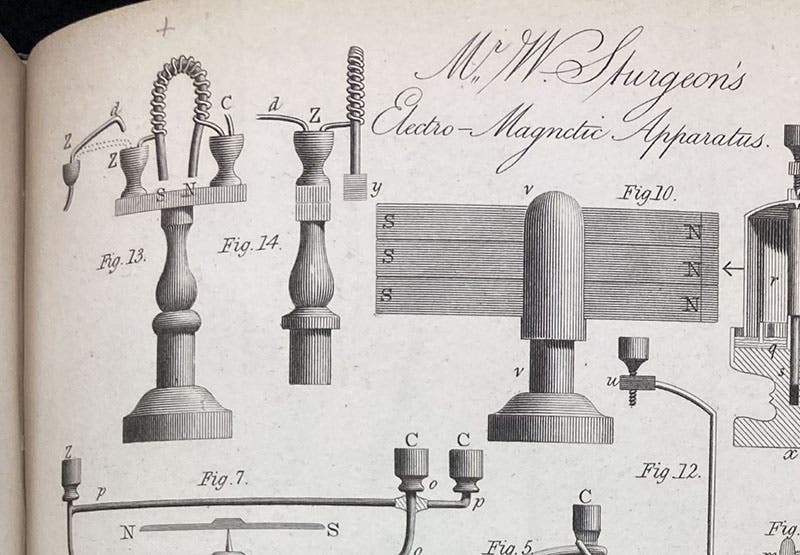

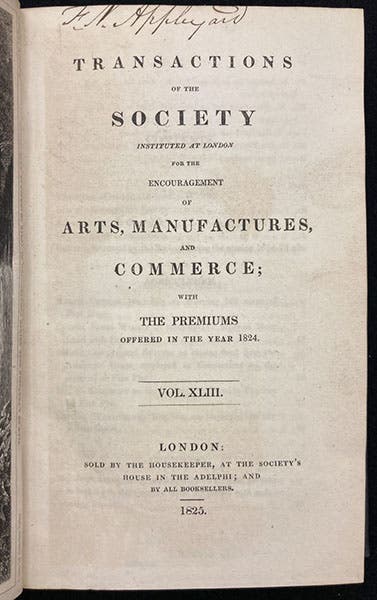

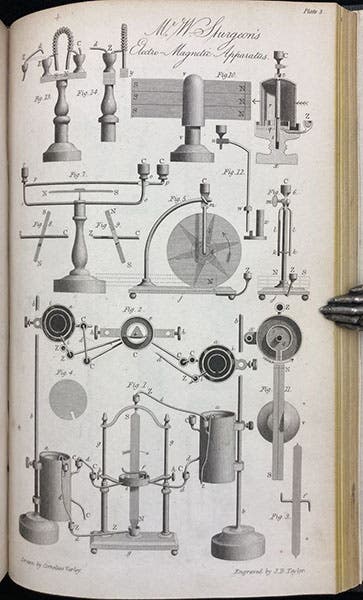

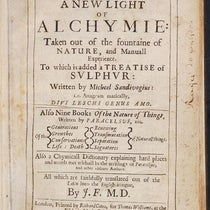

Sturgeon was a shoemaker’s son, and apprenticed to a shoemaker. He was a bright young man, and longed for something more intellectually challenging. Entirely self-taught, he enlisted and went to work for the East India Company, soon becoming a lecturer in their school. He was an avid experimenter, and as soon as the magnetic side of electricity was discovered, Sturgeon went to work. Within three years, he discovered that if you wrap a horseshoe-shaped soft iron core with wire (he used 18 turns) and connected the ends of the wire to a battery, the result was a powerful magnet – an "electromagnet" – that would lift many times its own weight. He announced his electromagnet in 1825 in a journal not often used by academic scientists: Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. But the engravings could not have been more clear (first and third images), and soon mainstream investigators like Michael Faraday and Joseph Henry were experimenting with electromagnetism.

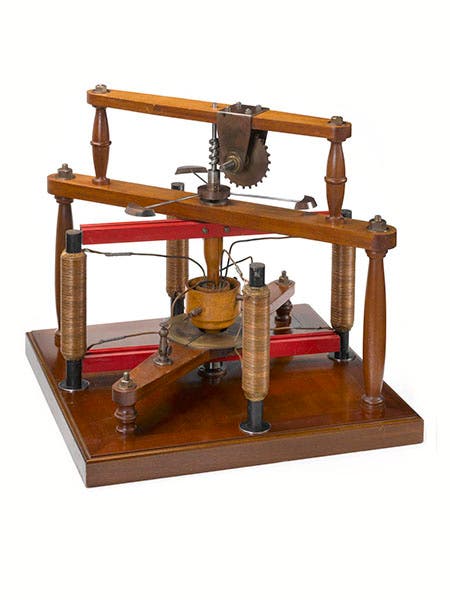

Leaving the East India Company, Sturgeon tried to earn his living as a professional lecturer and demonstrator. He was chosen to head up the Adelaide Gallery of Practical Science in London, the mission of which was to provide adult education in the sciences. He founded a journal, Annals of Electricity, Magnetism, & Chemistry, in 1836, the first devoted to electromagnetism, and he personally kept it going for 10 volumes before it succumbed to an impoverished subscription list (fourth image). Earlier, in 1832, he had succeeded in building a rotary electric DC motor that could turn a fireplace spit, the first such motor ever made. There is a replica on display in the Science Museum in London (fifth image).

When the London school failed, Sturgeon was selected to head up a similar institution in Manchester, the Royal Victoria Gallery of Practical Science, where he had a strong influence on a young student, James Joule. But that school failed as well. The public was unwilling, or unable, to pay the modest lecture fees.

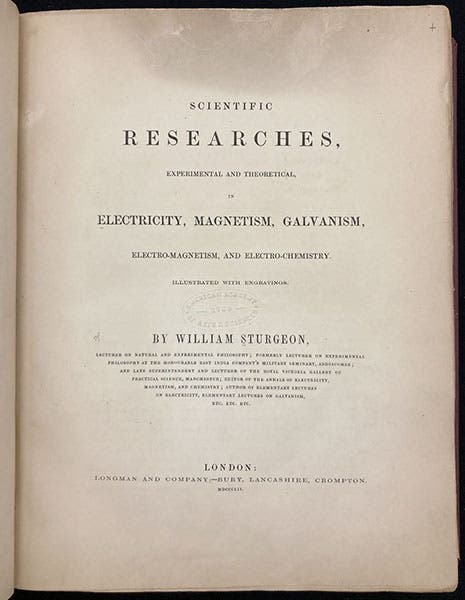

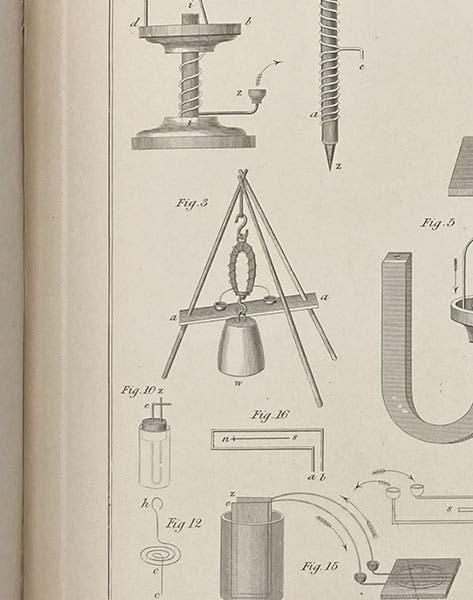

None of his efforts could keep Sturgeon afloat financially. He became more impoverished, although his friends did secure him a small pension. Sturgeon decided to publish an omnibus collecting all his experimental work in one volume, which he began issuing by subscription in 1850, but he died before that year was out. The issued fascicles were bound up and published with a title page in 1852, as Scientific Researches, Experimental and Theoretical: in Electricity, Magnetism, Galvanism, Electro-Magnetism, and Electro-Chemistry (sixth image). We have that set in our library, a much more handsome book, a small folio with many engravings, than one might expect, given the circumstances of its publication. I include a detail from a plate that shows his demonstration “tripod” electromagnet, which could lift ten pounds off the table when a wire from a battery was inserted into one of those little cups of mercury that functioned as connectors (seventh image).

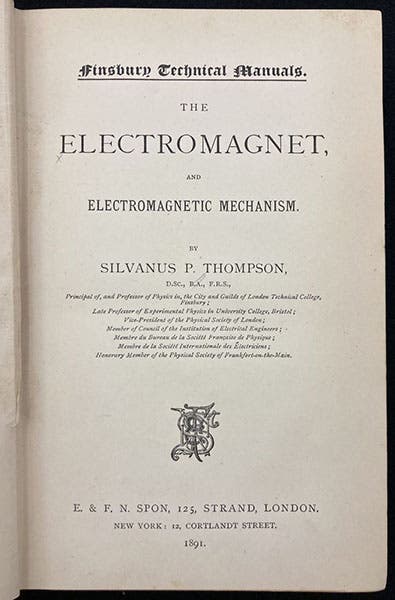

Joule wrote a heart-felt remembrance of Sturgeon in 1857, but I don’t think anyone read it. It was not until 1891 that Sturgeon got a second lease on life, when Silvanus P. Thompson, who would soon give us the first English translation of William Gilbert's De magnete (1600), published his own book, The Electromagnet, and Electromagnetic Mechanism (1891; eighth image).

Thompson began his work with Sturgeon, and put the 1825 engraving of the horseshoe electromagnet on page 3. He even included an 8-page biography of Sturgeon as an appendix (pp. 412-18; ninth image). But Thompson failed to secure scientific immortality for Sturgeon, who, a century later, is once again a footnote in histories of electrical science. And the reason I think is a social one – Sturgeon travelled in the wrong social circles. Demonstrators like Sturgeon, even if brilliant, were looked down upon by mainstream academic scientists in London and Oxbridge and were left out of the conversation, seldom invited to submit papers to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society or the Proceedings of the Royal Institution. His journal was considered a trade journal for practical electricians, not an academic journal for students of electrical science. He was out of the loop. And for posterity, that seemed to imply that he was irrelevant. But he most certainly was not.

Even the existence of a Sturgeon portrait is in question. Wikipedia shows one, an engraving, and dozens of other websites show versions of the same one. It may be a valid portrait. But no one who reproduces that portrait provides an original source. When Thompson wrote his bio of Sturgeon in 1891, he said there was only one portrait of Sturgeon, owned by his daughter, but he had never seen it, and it was an oil painting, not an engraving, and it has never been seen since. The fact that no engraved portrait existed in 1891 suggests strongly that the Sturgeon portrait in circulation shows someone else. I choose not to include it here. But I would love to find a certifiable rportrait, and will keep on looking, now that I am hooked on Sturgeon.

Sturgeon does have a gravestone, in Manchester (tenth image). He is identified on the stone as “The Electrician.” His lack of professional status followed him all the way to his grave.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.