Scientist of the Day - Bernhard Walther

Karl Galle

Karl Galle

Bernhard Walther, a German merchant and astronomer, died June 19, 1504; his birth date is unknown. Walther, a resident of Nuremberg, was the intellectual and instrumental heir of Johannes Regiomontanus, the Königsberg astronomer who moved to Nuremberg in 1471 and set up the first scientific printing press, intending to publish not only Ptolemy's Almagest, but also his own Epitome of the Almagest. His ambitions were nipped when he died suddenly in Rome in 1476. Walther had assisted Regiomontanus in both his astronomical and printing endeavors, and upon the death of his mentor, Walther bought up the instruments and library of Regiomontanus and acquired much of his observational data. Better yet, he continued the observational program, making regular observations of the planets right up until his death. Moreover, at a time when clocks did not have minute hands, Walther found a way, by counting teeth on a weight-driven clock, to get observations that were accurate to the minute.

For the last three years of his life, Walther lived in a house in Nuremberg that still stands. He got permission to add an observing window on the back of the attic floor, with an extended sill to hold his instruments (second image). From this window, he was twice able to record the position of the planet Mercury, a planet that doesn't get very far above the horizon in Nuremberg, giving him a total of three Mercury observations in all (he had recorded the planet once before, in 1491). Thirty-odd years later, Nicholas Copernicus was unable to see Mercury at all from the latitude of Frombork in Poland and feared that he would be unable to provide an accurate model for Mercury in his De revolutionibus (1543). Fortunately, Johannes Schöner of Nuremberg, who had acquired the observations of both Walther and Regiomontanus, provided Copernicus with the three Walther observations of Mercury, and the data set for Copernicus's book was complete.

Five years after his death, Walther's house, with its third-floor observing window, was purchased by Albrecht Dürer, the brilliant Nuremberg artist and printmaker, which is the main reason the house is still standing, and also the reason it is not called the Walther Haus, but rather the Albrecht Dürer Haus (third image). Our photos of the house and the window were taken by Karl Galle, a former fellow at our Library and author of an article published earlier this year, "Copernicus and the View from Dürer's Window (translating the German title), which appeared in Regiomontanusbote, the magazine of the Nuremberg Astronomical Society, and which inspired and informed today’s notice.

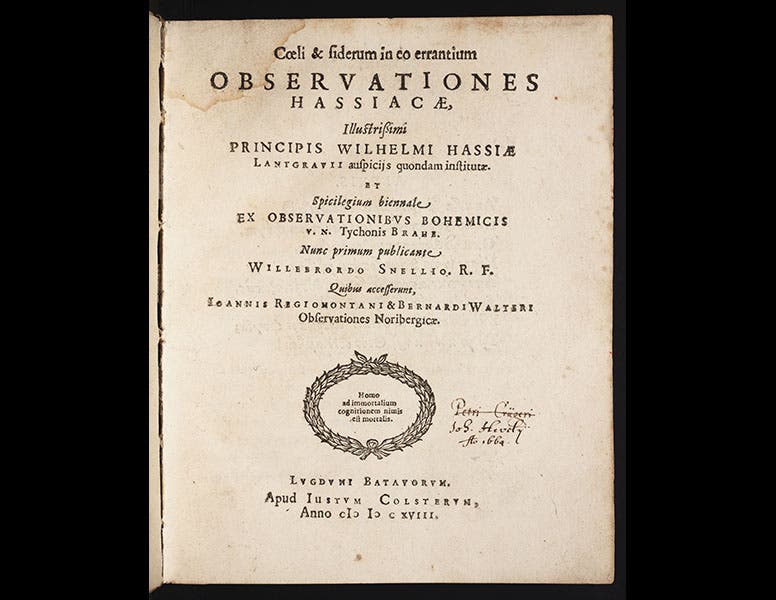

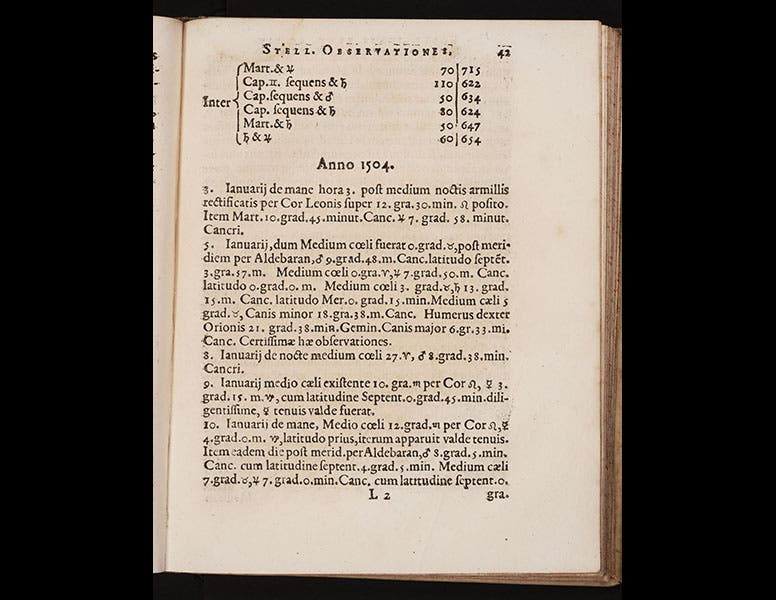

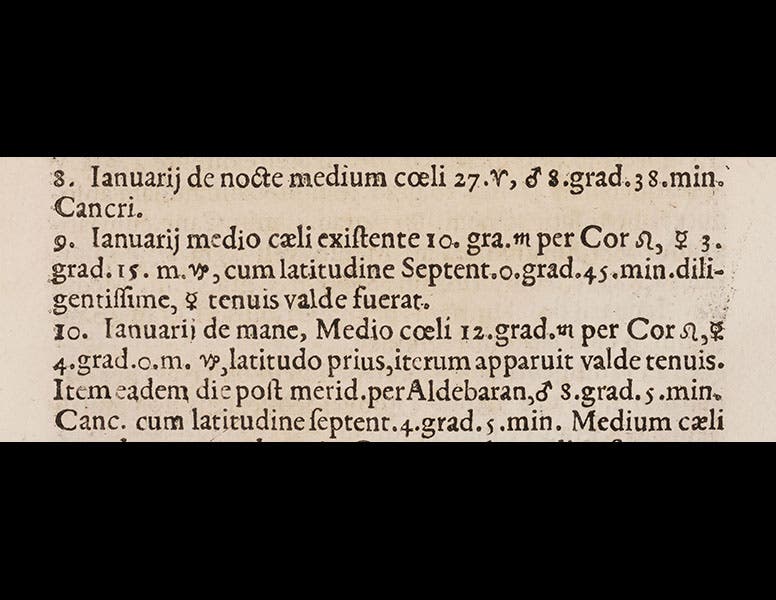

Walther never published his observations, and neither had Regiomontanus. Schöner published the observations of both astronomers in his Scripta (1544), a work we do not have in our Library. Fortunately, 74 years later, the Dutch astronomer Willebrord Snell republished the observations of Regiomontanus and Walther in his Coeli & siderum (1618), and this book we do have. We reproduce above the page (fifth image) and a detail from the page (sixth image) that shows Walther’s Mercury observation of January 9, 1504 (to spot it, it helps to know that the symbol for Mercury looks like a little circle with a crescent moon above and a cross below). Before we acquired this book, it was owned by the Gdansk astronomer Johannes Hevelius and his teacher, Peter Crüger (fourth image). That it also contains the Mercury observations of Bernhard Walther just makes it that much more special. Hevelius also provided us with our only semi-contemporary portrait of Walther, including him in a line-up of important observational astronomers in the frontispiece to his star catalog of 1690 (first image).

Finally, we might mention that the date of Walther’s death is currently under re-examination—recently discovered evidence suggests it might have been June 13 rather than June 19. We are sticking with the traditional date here.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)