Scientist of the Day - David Gregory

David Gregory, a Scottish astronomer and mathematician, was born June 3, 1659, in Aberdeen. Gregory was an excellent mathematician, and he became first a correspondent and then an acquaintance of Isaac Newton. It was Newton who secured for Gregory the Savilian professorship of geometry at Oxford, which post Gregory took up in 1691. Gregory’s Astronomiae, physicae & geometricae elementa (1702) was a very influential work and was translated into English in 1715; we have both versions here at the Library. His earlier work on optics, Catoptricae et dioptricae sphaericae elementa (1695), which we also have in our collections, has been scanned and is available online, if you are partial to perusing Latin mathematical works.

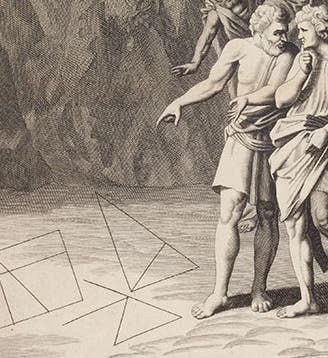

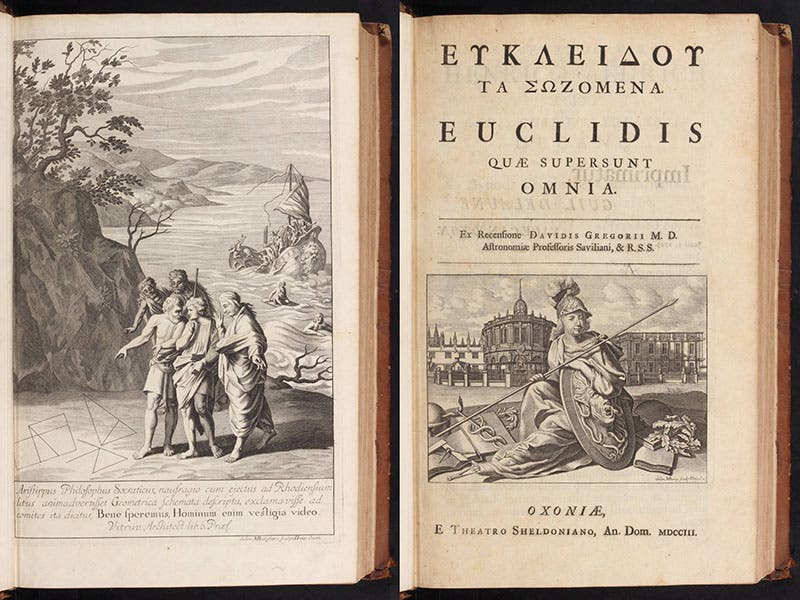

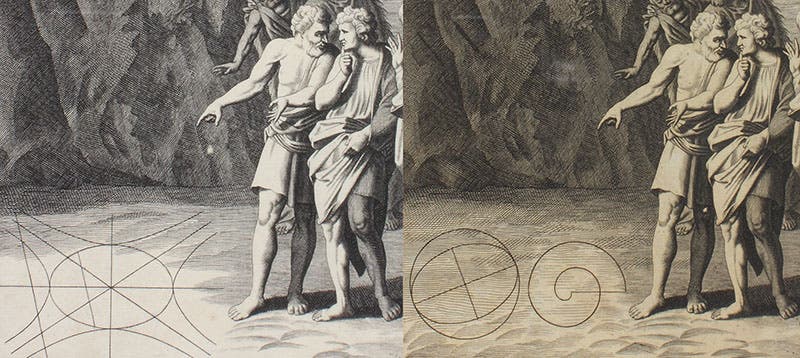

But today we are going to use Gregory as an excuse to talk about a frontispiece – in fact, three frontispieces. In 1703, Gregory published an edition of the works of Euclid in Greek and Latin. Issued in large quarto format by the Oxford University Press, the book included an introductory engraving designed by Michael Burghers (second image). The scene shows a group of men, apparently shipwrecked, standing on the shore, as one of them points to some triangles and other geometrical figures drawn in the sand (see detail, first image), oblivious to the agonies of the shipwreck still in progress. This illustrates a passage from Vitruvius, the ancient Roman architect, who recounted a story about Aristippus, who was shipwrecked with his companions on the island of Rhodes. But he spied some triangles in the sand, and said to his friends: Bene speremus, hominum enim vestigia video – “Cheer up, for I see the vestiges of mankind."

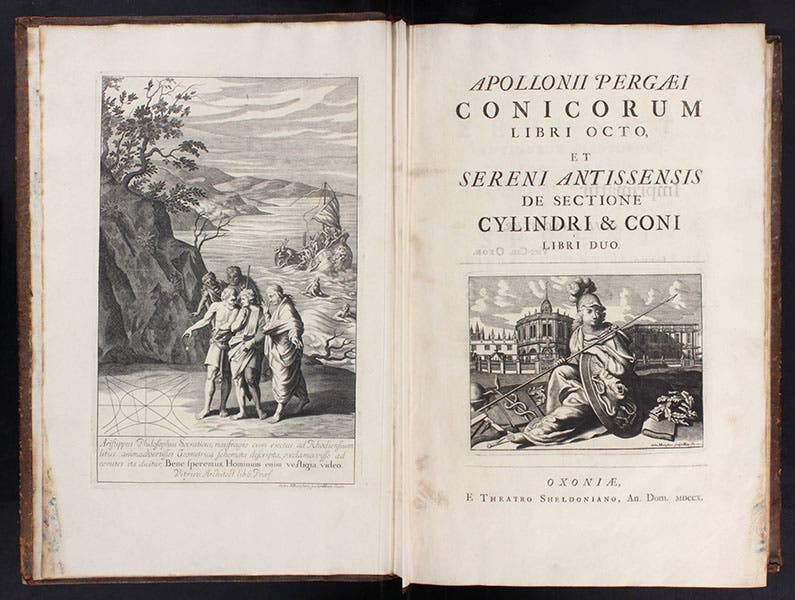

This is certainly a handsome frontispiece, so attractive – and probably so expensive – that the Oxford Press decided to use it again when they published the works of Apollonius in 1710. But the triangles and lines of the original engraving were not especially appropriate for a book on conic sections. So the plate was reworked, and the triangles were rubbed out and replaced by hyperbolas and parabolas (fourth and fifth images; detail in eighth image). They were still vestiges of humankind, just different ones.

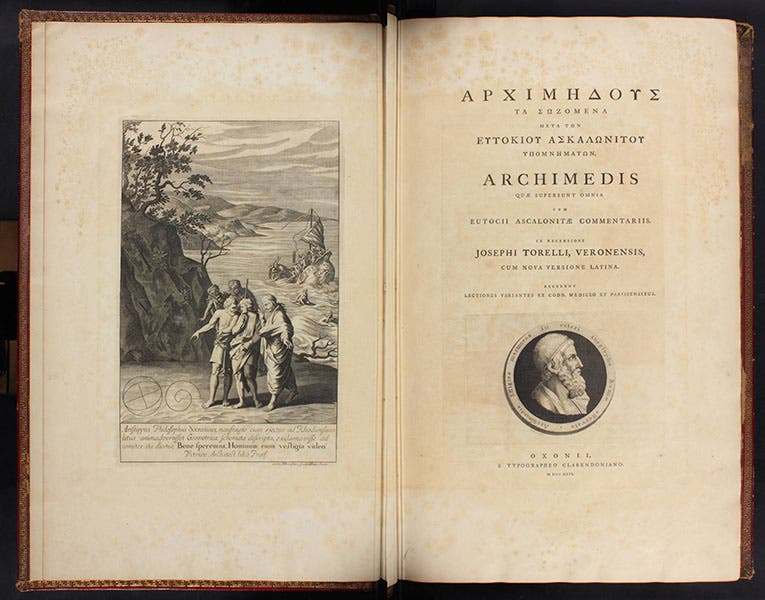

And then, four generations later, an entirely different set of Oxford University Press directors committed themselves to publishing a Greek/Latin edition of the works of Archimedes. The copper plate of 1703/1710 was apparently still lying around, and it was decided to use it yet again, despite the fact that the Archimedes folio would be four times as large as the Euclid quarto of 1703 (sixth and seventh images). This time the conic sections were erased and replaced by appropriate Archimedean figures, a spiral and a quadrature (see detail, ninth image). The vestiges of human kind became even more numerous.

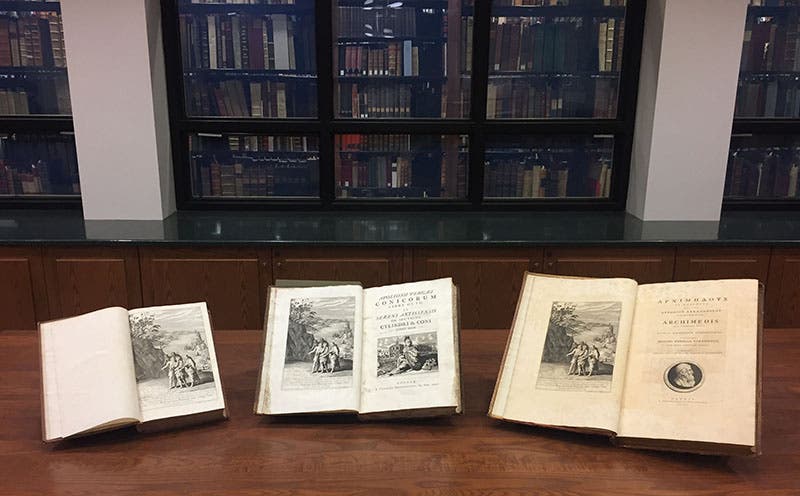

This was not the first time that a frontispiece or engraved title page was reused for a different book, but seldom has it been done more cleverly. There are not many libraries where one can see all three Variations on a Theme by Michael Burghers at the same time; we couldn’t resist posing them for a photograph (tenth and last image).

The editions of Euclid (left), Apollonius (center), and Archimedes, with their frontispieces, on display in the reading room, outside the glass vault (Linda Hall Library)

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)