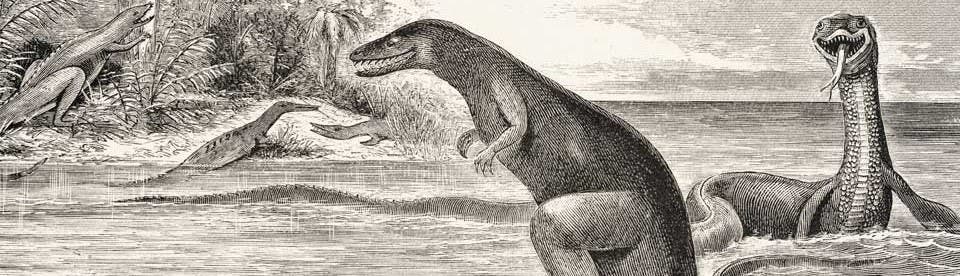

Nimble Diplodocus, 1907

The Carnegie Museum was not alone in finding Diplodocus remains; the American Museum of Natural History recovered two partial Diplodocus skeletons in Wyoming at about the same time as Hatcher was finding his, which brought this slender sauropod to the attention of Henry Fairfield Osborn. In an 1899 paper, Osborn took issue with the conventional picture of sauropods, at least as applied to Diplodocus.

"There is a traditional view," he said, "that these animals were ponderous and sluggish. This view may apply in a measure to Brontosaurus. In the case of Diplodocus it is certainly unsupported by facts."

Osborn in addition proposed a novel function for the tail, which he thought could function "as a lever...to raise the entire forward portion of the body upwards. Thus the quadrupedal Dinosaurs occasionally assumed the position characteristic of the bipedal dinosaurs--namely, a tripodal position."

In 1907 the American Museum of Natural History prepared one of its two Diplodocus specimens for presentation to the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt. To celebrate the occasion, Scientific American asked Charles Knight for a cover painting. Knight obliged and gave wonderful form to Osborn's vision with this remarkable painting. We would not again see the like of such a light-footed sauropod until the American Museum erected its rearing Barosaurus mount in 1991. The Knight cover painting was accompanied by a short article on the Senckenberg Diplodocus mount.

Diplodocus, the Human Dimension, 1899

This partial skeleton of Diplodocus was found by Barnum Brown at Como Bluffs, Wyoming, in 1897, and later excavated by J. L. Wortman and mounted in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The pencil restoration is unusual for the time in that it includes a human figure to provide scale. Osborn would later use a human to similar effect in the famous restoration of Tyrannosaurus in 1905, although there the human is more fittingly shown as a skeleton.

A Diplodocus goes to Germany, 1907

The Diplodocus mount sent to Great Britain in 1905 by the Carnegie Museum was a plaster replica. This mount, presented to the new Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1907, was the real thing. It had been found at Bone Cabin Quarry in Wyoming in 1899 by W. D. Matthew and P. Kaison. The cost of preparing this mount was born personally by the president of the American Museum of Natural History, Morris K. Jessup.

The Scientific American article also includes a photograph of Charles Knight’s charming sculptural restoration of Diplodocus, which was on display with the Diplodocus mount at the American Museum in New York.