Scientist of the Day - Julius Berkowski

On July 28, 1851, there was a total eclipse of the sun visible in Europe. This was the first eclipse for which a massive observational effort was mounted, especially in England. Many questions had arisen since previous eclipses. An astronomer named Francis Bailly had observed tiny beads just at the moment of totality (now called “Baily’s beads”) – were these real? Others had observed prominences at totality – were these prominences on the moon or on the sun? One thing the English did not try to do was photograph the eclipse. Photography had been invented in 1839 by Louis Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot, but the only available processes were the daguerreotype and the talbotype, and both required specialized equipment and long exposures. A daguerreotype of the moon had been taken and was being exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851, which greatly impressed astronomers, but no one thought you could do that with a solar eclipse.

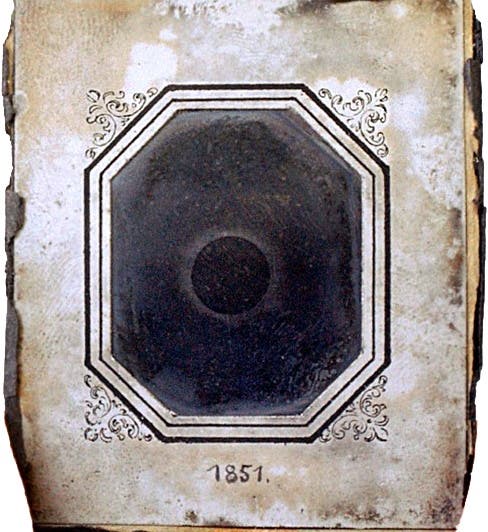

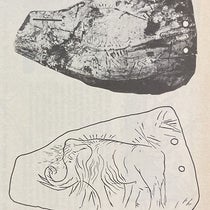

So it was left to a nearly unknown photographer named Johann Julius Berkowski at the Royal Observatory in Königsberg in Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia) to make the attempt. With an 84 second exposure, using a small refractor, he captured a single daguerreotype that is the first successful photographic image of a total solar eclipse. Daguerreotypes cannot be printed, but the observatory director had an engraving made in 1854. Berkowski made 3 copies (by taking daguerreotypes of his original daguerreotype), and at least one of these 2nd-generaton daguerreotypes survives, at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena (first image here). Also, photographic copies of the original were made in 1891, before the original disappeared.

The moon in the original daguerreotype was tiny - less than 8 mm across. The 2nd-generation image (the one at Jena) is just a little larger, but the entire print is only about 2 x 2.3 inches. Still, for all its lack of detail, Berkowski's 1851 image showed the potential for photography in astronomy, and for the next eclipse of July 18, 1860, everyone had cameras, using a new kind of photographic method known as the wet collodion process, which did create reproducible images. Solar astronomy would never be the same, thanks to the man so nearly anonymous that until very recently, we didn’t even know his full name.

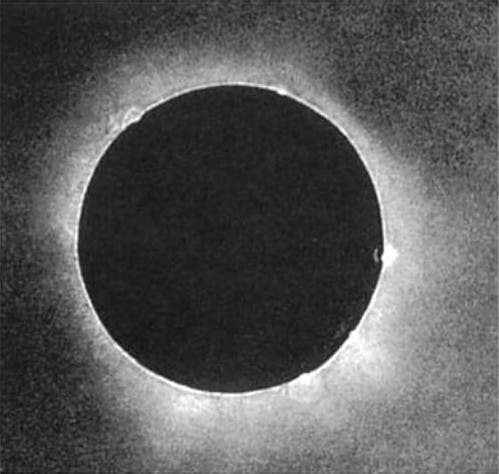

Wikipedia has an article on the July 28, 1851 eclipse, and the image there (second image here) is not the original daguerreotype or the Jena 2nd-generation copy. Whether it is the 1854 engraving or one of the photographic copies of 1891 is not clear. The full name of Berkowski first came to light in a German article posted as a PDF in 2013, but not, apparently, peer-reviewed or published in an academic journal. However, the authors have written and published earlier articles on the Berkowski daguerreotype that are authoritative, so we assume this new information is reliable.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.