Scientist of the Day - LAGEOS 1

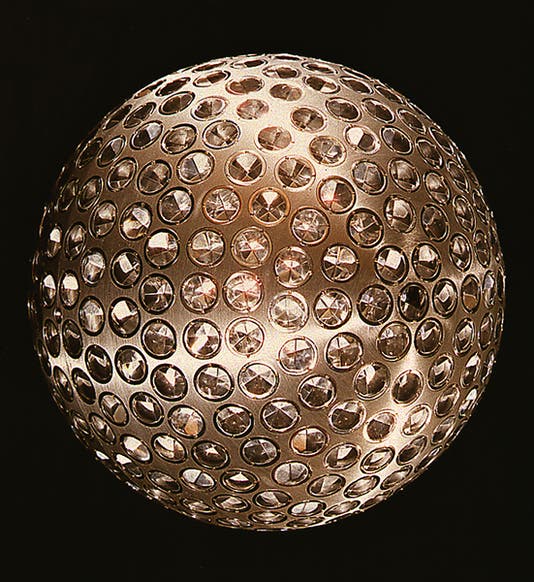

LAGEOS 1, a geodetic satellite, was launched into orbit on May 4, 1976. As satellites go, this one had a classy Dior-style look, the kind of thing that would have looked right at home hanging from the ceiling in a high-class disco (first image). The facets that look like jewels are actually what NASA calls retroreflectors, each one designed to take a laser beam and send it back exactly where it came from. The sphere itself was made of aluminum-and brass, measured 24 inches across, and weighed just over 900 pounds. From a distance it resembled a shiny metallic golf ball, with precisely 426 dimples. There were no electronics or other moving parts aboard, so LAGEOS 1 functioned as a passive reflector. A ground station would pulse a laser beam at the satellite; the beam would be reflected, the time of transit would be measured, and the station would know its precise position to an accuracy of about one inch. LAGEOS 1 was the great-great granddaddy of the current GPS system that allows you to navigate your car even though you are totally incapable of using a map.

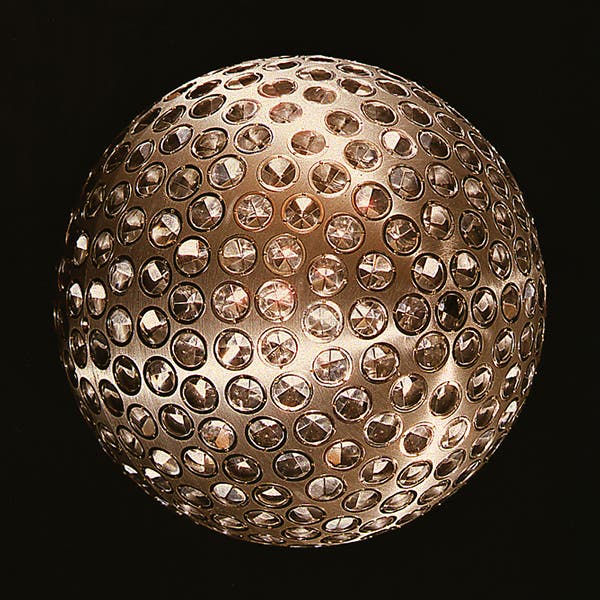

But if that were all there were to LAGEOS 1, we would not be talking about it today, handsome though it may be. We celerate its birthday because LAGEOS 1 carried a message to extra-terrestrials, marking it, at the time of its launch, only the third such attempt by humankind to send into space a physical message to life elsewhere. The first two were plaques that were attached to Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, which were launched in 1972 and 1973 and are right now on their way out of the solar system. We will not stray from our topic by discussing the Pioneer message (you can see the Pioneer plaque in its Wikipedia article), except to say that it was somewhat uninspired. LAGEOS 1 also has a plaque, and its message is brilliant. Take a look before we discuss it (second image, just below, with details in third and fourth images).

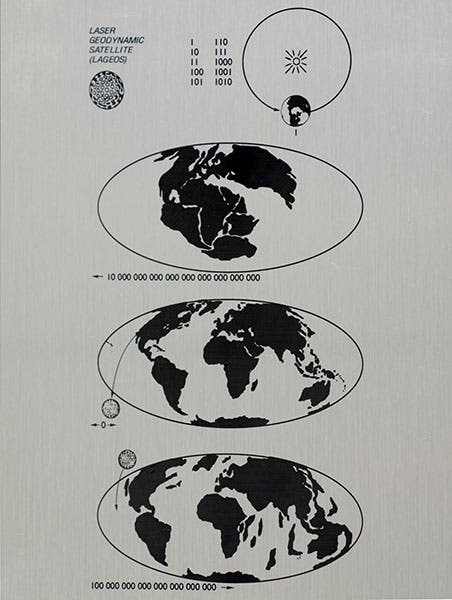

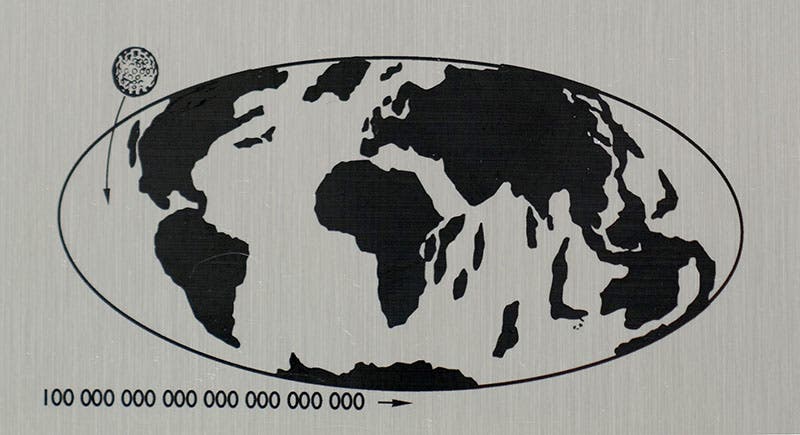

You have no doubt noticed that there are three world maps on the plaque, and if you are sharp, you recognize that the central image looks like a current map of the world, but the top and bottom maps are different. The top map depicts Pangaea, the supercontinent that included all of the earth's landmasses and began to break up about 240 million years ago. The bottom map shows the earth's continents as they will appear in 8.4 million years, with East Africa splitting off from its current parent, and Baja California up near Alaska. But what about all the 1's and 0's? Those are binary numbers (invented by Chandra Beinaree, as readers of our April Fool anniversary for 2015 might remember), and the top of the plaque counts to ten in binary, as a way of showing that 1000, for example, represents the quantity 8. At top right, we see a diagram of LAGEOS 1 circling a central radiating symbol, evidently the Sun, with the number "1" alongside. The plaque designer is attempting to say that "1", as used on this plaque, represents one year.

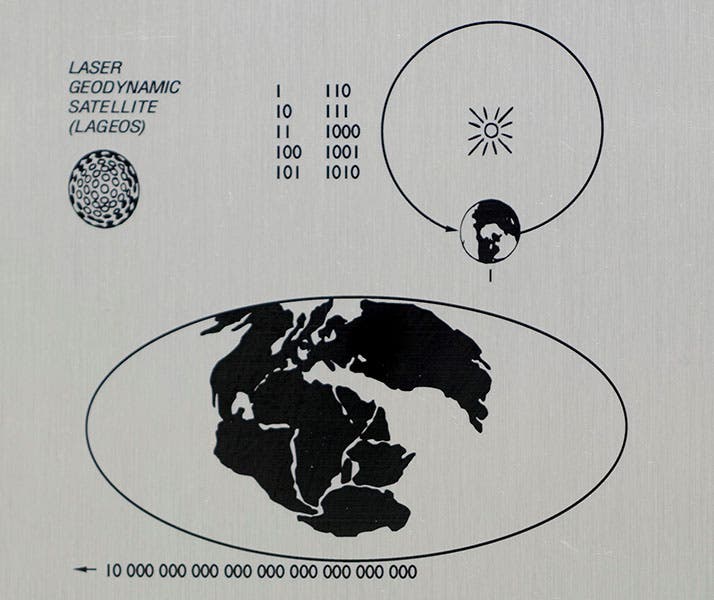

So now back to the maps. The top map has the label “268 million” in binary, with an arrow pointing left (third image, just above). Evidently, this is intended to mean that the first map represents the earth as it was 268 million years ago (268 million is a round number in binary – the more accurate 240 million has a long array of 1s and 0s, and was wisely not used). Will ET know that a left-pointing arrow means “ago”? That is a good question. The central map has the label “0”, indicating that it shows the world at the time the satellite was launched, a tiny image of which you can see at the left. And the bottom map has a right arrow and the number “8.4 million” in binary, implying that this is what the earth will look like 8.4 million years from now (fourth image, below). Why 8.4 million? Because the orbital scientists calculated that the satellite should remain in orbit for at least 8 million years, so that was their end point. And in the third map, you will notice the satellite falling back to Earth.

Top third of the LAGEOS 1 plaque, explaining the binary code, and showing the Earth as it appeared 268 million years ago (nasa.gov)

And what makes this brilliant? Well, think where this plaque is – attached to a satellite that orbits the earth 3700 miles up. So if ET ever stumbles on LAGEOS 1 and extracts the plaque (it is on the inside, so as not to interfere with the retroreflectors), he, she, or it can look at the plaque with one eye, and the Earth itself with the other (or others). If the earth looks like the central map, they will know that the satellite was orbited relatively recently. But if the earth looks like the bottom picture, or somewhere in between, then our visitor will know that millions of years ago we were smart enough to launch a rocket into space, and, assuming we are no longer in evidence, stupid enough to destroy our one and only home.

Bottom third of the LAGEOS 1 plaque, showing the Earth as it will appear in 8.4 million years (nasa.gov)

LAGEOS, as the plaque tells us at upper left, is an acronym for LAser GEOdynamic Satellite. And yes, there was a LAGEOS 2, launched in 1992. This one apparently did not have the plaque attached – I do not know why – and was released from the Space Shuttle Columbia. Both satellites are still functioning, as they ought to be, if their projected orbital lifetime is 8.4 million years. A geophysicist could probably tell you have much the continents have moved since LAGEOS 1 was launched 46 years ago, but I cannot. But I can connect you to the official website of LAGEOS 1 and 2. I don’t think it is updated very often.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.