Scientist of the Day - Leonhart Fuchs

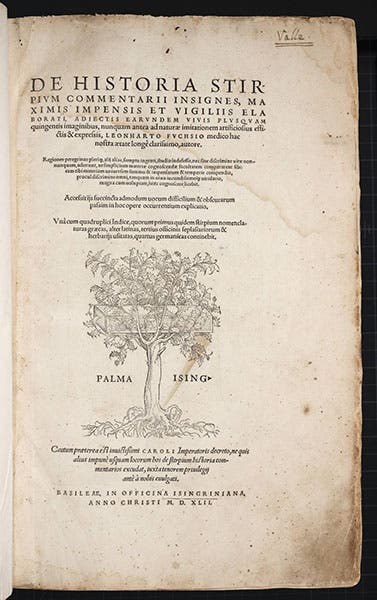

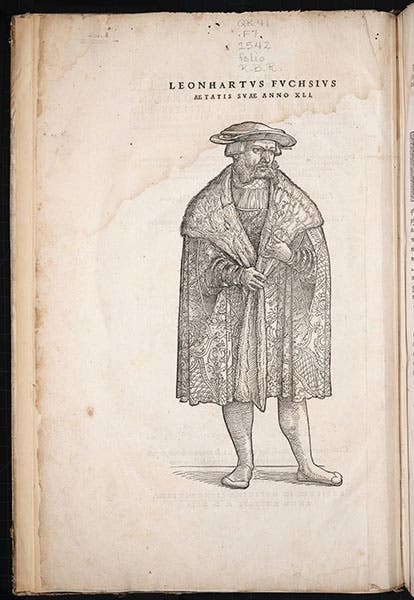

Leonhart Fuchs, a German botanist, was born Jan. 17, 1501. Fuchs taught in Tübingen, and in 1542 he published a botanical work that would transform botany, medicine, and natural history in general. Fuch's De historia stirpiium (On a history of plants), a large folio, was notable for including over 500 woodcuts of plants, "drawn from life," to illustrate the text.

There had been an earlier book by Otto Brunfels, Vivae eicones herbarum (Living Images of Plants, 1530), with life-like woodcuts of plants, drawn by an artist from nature, but in this case, the impetus came from the publisher; the author of the text, Brunfels, was not too keen about the idea. Fuchs, on the other hand, felt strongly that illustrations that were accurate and well-drawn would be an asset to the text, and he took the lead in hiring the artists. Surprisingly to us, Fuchs was arguing against a long-standing tradition, going all the way back to Dioscorides and Pliny, that in botany, images tended to mislead and were better left out.

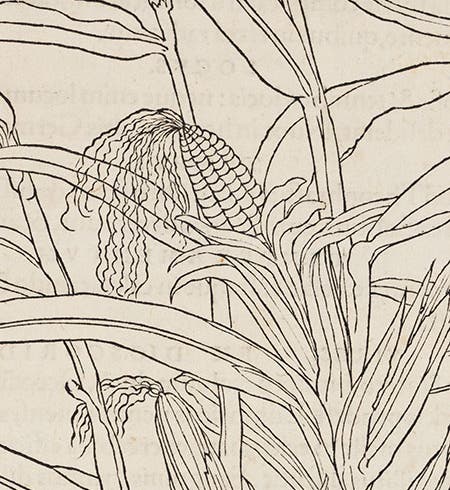

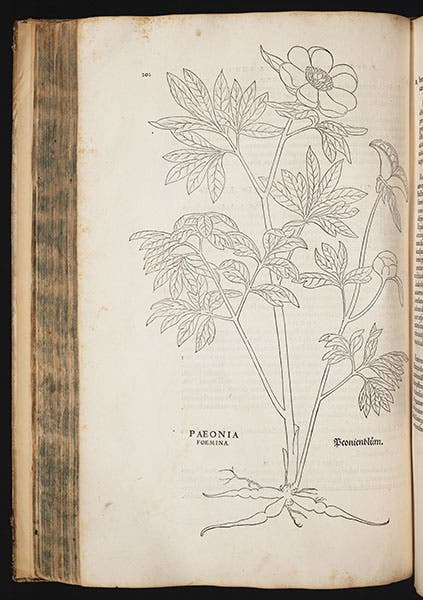

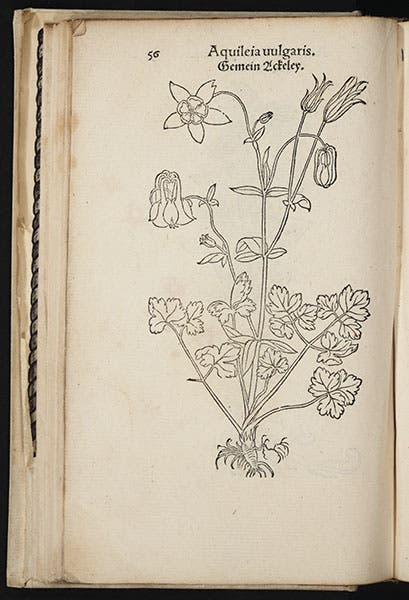

There are a number of ways to illustrate a plant. You can draw it exactly as it appears at that moment, flaws and all, which is what Brunfels' artist did. The problem is that plants change appearance as the seasons go by, having buds, flowers, fruits and seeds in succession. And plants with broken stalks and insect-eaten leaves tend to offend us aesthetically, even if true to nature. So Fuchs asked his artists to show us ideal plants, with no imperfections, and to make the image a time-lapse composite, depicting all the stages of a plant’s blooming process, including flowers on one side, seeds on another. The result is an image of a plant that you will never find in nature, but one very useful for botanical education.

There are other choices that have to be made for a printed image. One can ask the artist to shade the image to give a more life-like appearance. Or one can omit the shading and plan on using hand-coloring to provide relief. That is what Fuchs preferred, and why the woodcut lines on Fuchs' illustrations are so thin, providing outline and not contour. Our copy is uncolored, which is great for students of the print, but many copies of De historia stirpium are colored, which is better for students of botany.

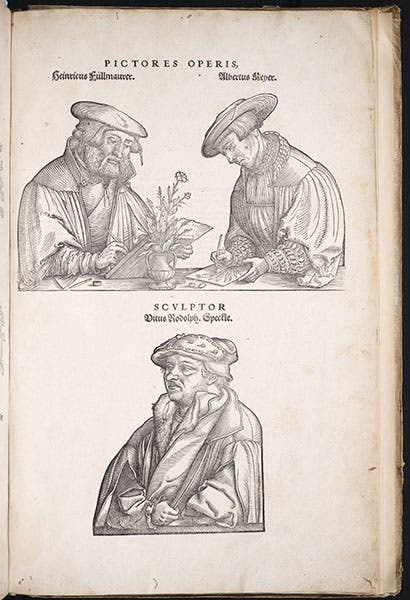

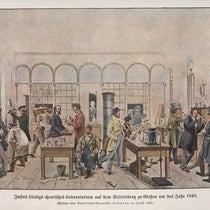

We know who Fuchs’ used to illustrate his book because he thanked them in the text: Albrecht Meyer drew the plants; Heinrich Füllmaurer transferred the drawings to the woodblocks, and Veit Rudolf Specklin made the actual woodcuts. Moreover, in an unprecedented fashion, Fuchs included a woodcut portrait of all three at work (fourth image). Granted, the artists’ portrait was at the very end of the book, and Fuchs’ own portrait (fifth image) was at the front, but still, the artists received credit, which is more than one can say for the near contemporary and equally revolutionary work, Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica (1543), where the artist was not mentioned at all.

In 1545, Fuchs published a small (octavo) version of his herbal, with completely redrawn woodcuts. In some ways, these are even more attractive than the folio originals. We show a columbine from the 1545 edition (sixth image). The other plants shown here are maize (first image, a detail) and a peony (third image), both from the 1542 folio edition. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.