Scientist of the Day - Samuel David Gross

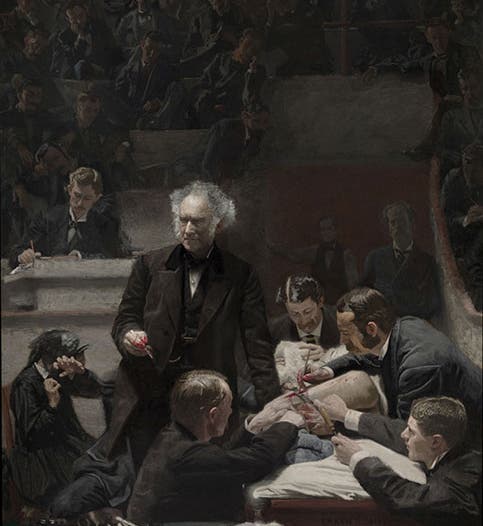

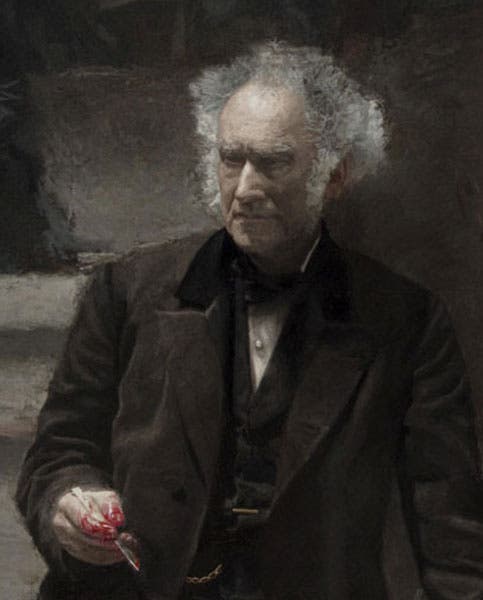

Samuel David Gross, an American surgeon, was born July 8, 1805. Gross attended the brand-new Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in the mid-1820s, and then taught pathological anatomy for some years at the Medical College of Ohio in Cincinnati. When that school folded, he took up a similar academic position in Louisville. In 1856, he returned to Jefferson Medical College as professor of surgery and taught there for the rest of his career. He was quite well respected and served several times as president of the American Medical Association. But still, he would probably not be much remembered today, were it not for the fact that, in 1875, he was the subject of a painting by the great American artist Thomas Eakins. The Gross Clinic, as it is usually called, is a large canvas, some 8 feet tall and 6.5 feet across. Gross was 70 years old at the time of the painting, which depicts a surgical operation on the leg of a young man, being performed in a medical amphitheater, with Gross both presiding and participating (notice his bloody hand holding a scalpel (first image). The Gross Clinic is considered to be one of the finest 19th-century American paintings – by many critics, the single finest 19th-century American painting – because of both its masterful artistry and its graphic realism, and it is equally significant in the history of medicine, since it shows surgery maturing into a healing discipline, where the surgeon can now cure a disease instead of merely lopping off the afflicted limb. And since this is a post on Dr. Gross, we should show you a detail of the painting, focused on Eakins’ depiction of Gross (second image).

The painting was completed in time for the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia, but the selection committee rejected it, supposedly because of the bloody nature of the operation, and perhaps because of the traumatized woman (presumably the boy's mother) at center left. So the painting had to be displayed at the nearby U.S. Army hospital; you can see it hanging in a hospital ward in a contemporary photograph. It was afterwards sold for $200, acquired by Jefferson Medical College alumni, who gave it to the College in 1878, and there it hung for almost 130 years, as it greatly appreciated in value. Finally, in 2006, the College decided to sell it to the new Crystal Bridges Museum in Arkansas for a cool $68 million. Philadelphians were understandably outraged at the threatened loss of their masterpiece and were determined to keep it in Philadelphia. Fund-raising efforts were partially successful, and the painting was sold in 2007 to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it hangs today. But both museums had to deaccession a number of paintings – including several by Eakins – to raise the rest of the funds. Crystal Bridges got Eakins’ A Portrait of Benjamin Rand instead.

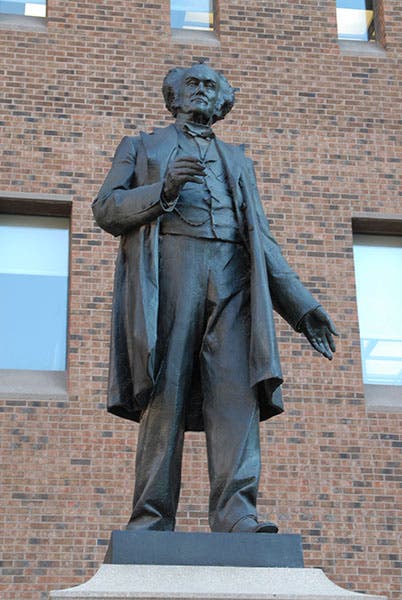

Bedazzled by the Gross Clinic, we easily forget that Samuel Gross has one other memorial in Philadelphia. In 1897, the American sculptor Stirling Calder unveiled a bronze statue of Gross, which was erected in Washington, D.C., near the U.S. Capitol. But in 1970, it was relocated to the campus of Jefferson Medical College, where it still stands, replicating the pose in Eakins’ painting (third image). Except that Jefferson Medical College, apparently fond of selling off its heritage, was renamed Sidney Kimmel Medical College in 2014, after a donor, and is now part of Jefferson, i.e., Thomas Jefferson University. The statue, however, has not moved. Calder was the father of the well-known mobile designer, Alexander Calder. Stirling is best known for a statue he did of Leif Erikson that was given to the people of Iceland by the United States and now seems to function as their Statue of Liberty. In our post on Erikson, we focused on American representations of the great Icelandic explorer and did not show Calder’s statue of Erikson in Reykjavik. You can see it here. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.