Scientist of the Day - Chester Stock

Chester Stock, an American vertebrate paleontologist, was born in San Francisco on Jan. 28, 1892. He attended the University of California – Berkeley and came under the spell of John C Merriam, the first prominent student of vertebrate fossils on the west coast. Merriam was one of the first to realize that the tar pits at Rancho La Brea might provide the key to understanding the mammals of the Pleistocene in southern California. Merriam extracted hundreds of skeletons of Smilodon, the saber-toothed cat, and Aenocyon dirus, the dire wolf, from the tar pits. Stock, however, focused on the giant ground sloths that were preserved at La Brea. His work would earn him a position as professor of vertebrate paleontology at the newly founded California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

Giant ground sloths have played a historic role in the history of vertebrate paleontology, more so than any other fossil mammal other than the mastodon and mammoth. The first mounted skeleton of a ground sloth, a Megatherium, was unveiled by Juan Bautista Bru de Ramon in Madrid in 1796, and Georges Cuvier included details of that skeleton in his Research on Fossil Bones in 1812. Thomas Jefferson in 1799 published images of the claws of a ground sloth found in Virginia that he called Mylodon, and Charles Darwin brought back a ground sloth specimen from South America on his voyage on HMS Beagle. Richard Owen, who identified Darwin's specimen, wrote full-length monographs on Mylodon (1842) and Megatherium (1860). Joseph Leidy, the first great American vertebrate paleontologist, published his own monograph on North American ground sloths in 1855, which we discussed in a post on Leidy.

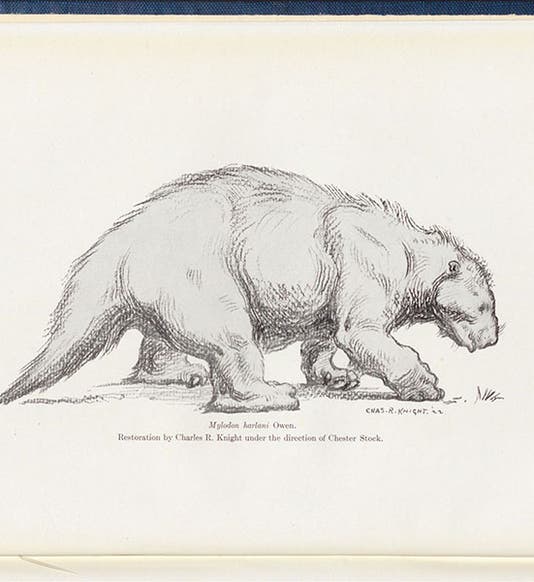

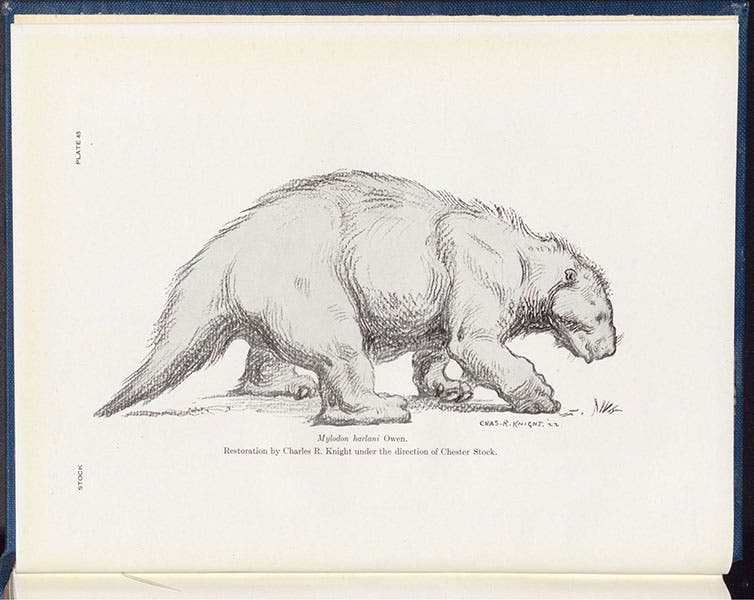

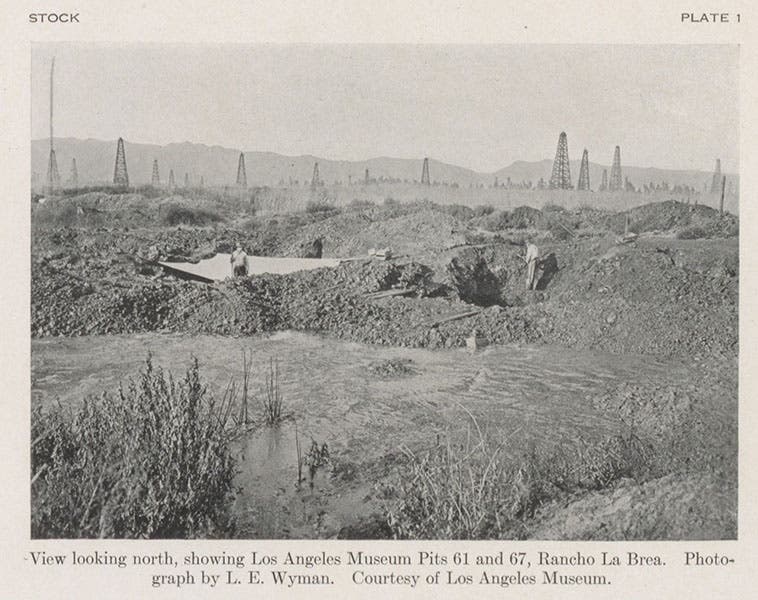

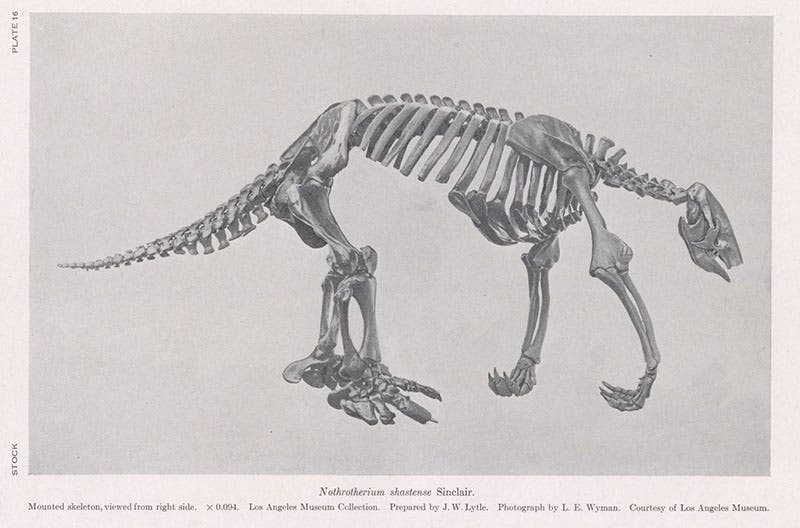

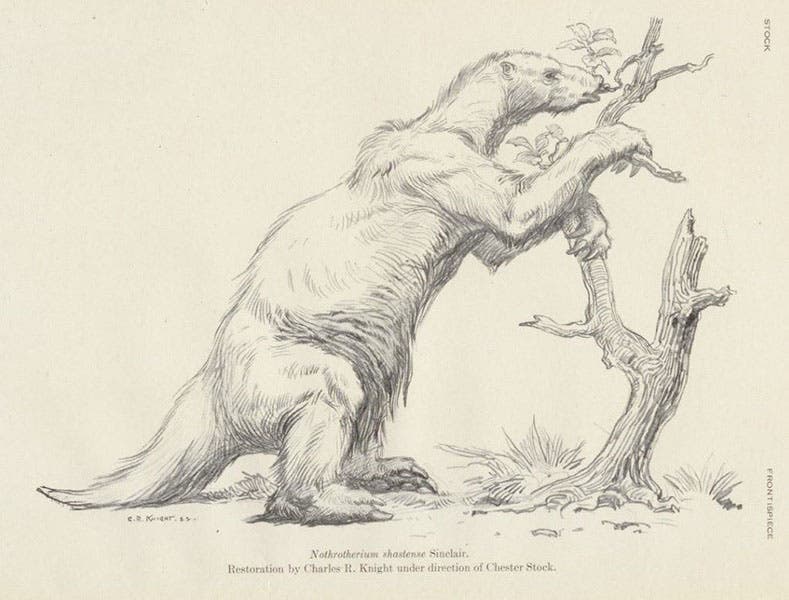

So Chester Stock was keeping fine company when he published his own monograph on the prehistoric ground sloths of Rancho La Brea, which he called Cenozoic Gravigrade Edentates of Western North America, where gravigrade means slow and lumbering and edentates are mammals with few or no teeth, such as sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. His book is abundantly illustrated with photos of sites at La Brea, skeletal reconstructions, drawings of bones, and most charmingly, two pencil sketches by the distinguished father of paleoart, Charles Knight. All of our images here come from the monograph on edentates, except for the portrait and the final photograph.

The frontispiece (sixth image) is a life restoration by Knight of Nothrotherium shastense, the primary species of large ground sloth found at La Brea. The very last plate in the book, the other Knight sketch, shows the smaller distant relative, Mylodon harlani (now Paramylodon harlani) (first image).

Some years back we wrote our first post on Stock, in which our focus was on Rancho La Brea rather than Stock, and most of the images came from a guide to La Brea that Stock wrote in 1930, although we did show the Knight frontispiece from the 1925 book that we are featuring today.

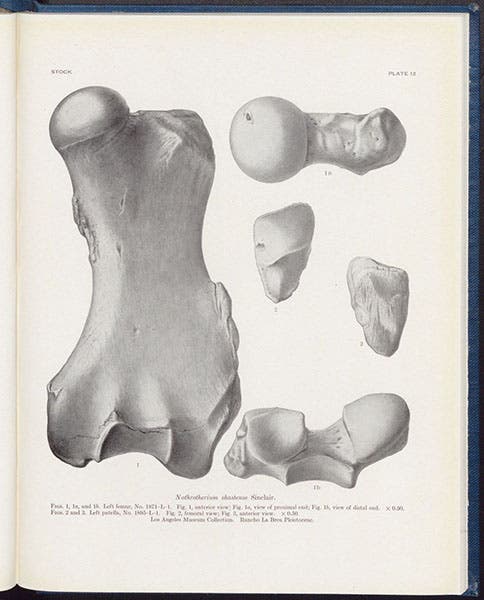

The 1925 monograph has quite a few photographs of individual groups of bones of Nothrotherium and Mylodon, such as the femur in our fifth image. The captions say that these are photographs, but it appears to me that they are not photographs of bones, but photographs of drawings of bones, and the drawings are exquisite. I do not know who made them. They remind me of the drawings made by Stock’s contemporary Erwin Christman at the American Museum of Natural History, some of which you can see at our post on Christman.

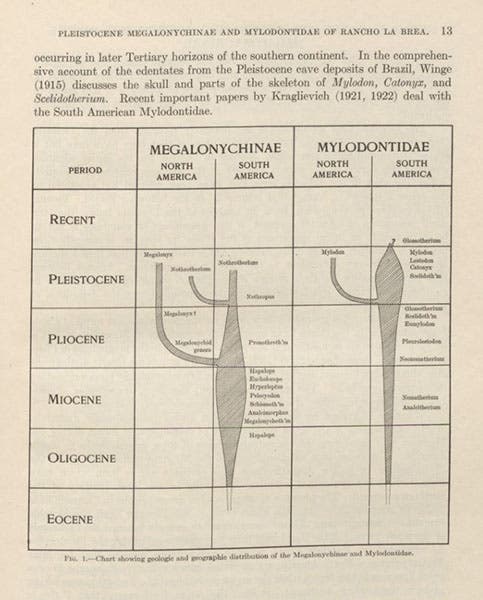

One of the illustrations Stock included is a spindle diagram charting the evolutionary history of Nothrotherium and Mylodon (seventh image). Spindle diagrams had been in use for nearly 100 years ( see our post on Louis Agassiz's fossil fish) but they were still infrequent in 1925. A spindle diagram has time as its vertical dimension and abundance as the horizontal one, and the result looks like a spindle, thicker when the species or genus is more abundant and thin when it was scarce, and being cut off when it goes extinct. Both ground sloth spindles terminate in the late Pleistocene.

One fact I did not discover is the location of Stock's grave or memorial stone. He is not listed on the FindaGrave website. If anyone knows more about this, please let me know. We use instead as a monument one of the Paramylodons that Stock pulled from the tar pits at La Brea and which has been mounted and put on display at the museum there (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.