Scientist of the Day - Edmund Beckett Denison

Edmund Beckett Denison, a lawyer, architect, and amateur horologist (time-keeping designer), died Apr. 29, 1905, at the age of 88. At the time of his death, he was known as Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe. But when he designed the tower clock for the new Palace of Westminster in the 1850s and commissioned its bells, including Big Ben, he was known as Edmund Beckett Denison.

After the old Palace of Westminster (home of the Houses of Parliament) burned down in 1834, the task of rebuilding was begun immediately, with Charles Barry as principal architect, who employed a Perpendicular Gothic Revival design. It was decided rather late to add a clock tower, which was designed by Augustus Pugin, who also designed the beautiful clock faces (a close-up of which you can see at our post on Pugin). There was a bit of a battle to see who would design the mechanism for the clock, which would be the largest striking clock in the world. On one side there was Benjamin Vulliamy, a very successful tower clock designer with many successes on his resume, but who was rather traditional. Opposing him was the Astronomer Royal, George Airy, who wanted an "astrononmical clock" in the new tower, one regulated by "galvanic" (electrical) signals from Greenwich Observatory. In Airy's corner, initially, was Denison, a well-respected amateur expert in horology, who did not think much of Vulliamy's antiquated clock mechanisms. Eventually, the Lords in charge rejected Vulliamy and selected Airy and Denison to be responsible for the clock. Denison designed the mechanism, which Airy approved, in the early 1850s. Their chosen clockmaker was Edward John Dent.

As it happened, Denison and Airy turned out to have different ideas about how the tower clock should communicate the time to London. Airy wanted electrical signals to keep time; Denison wanted to communicate the time with bells. The first hourly strike of the big bell should be accurate to the second, and it should be heard throughout Parliament and a large part of the borough of Westminster. Eventually, Airy dropped out of the project, and Denison took charge. Edward Dent dropped out as well, dying suddenly, and his place was taken by his adopted son, Frederick Dent.

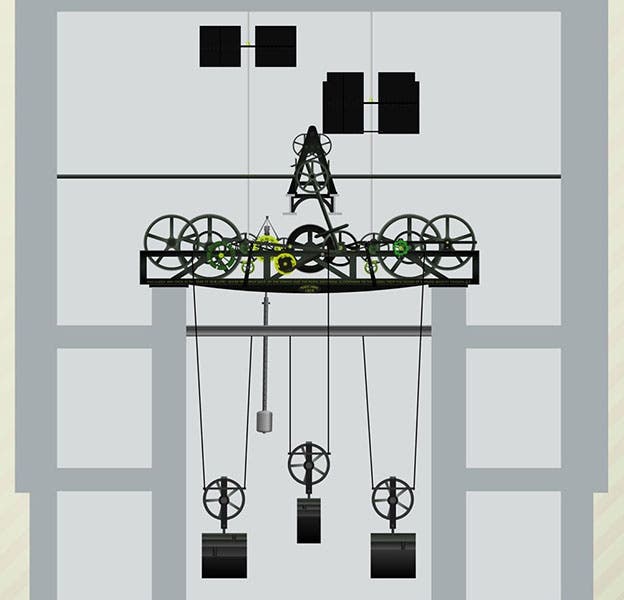

The tower clock mechanism, as designed by Denison and constructed by Edward and Frederick Dent, is quite a formidable piece of machinery, as you can see (third image). It had to be powerful enough to drive enormous hands on the four faces of the clock and to peal the bells. Denison and Airy had agreed on an escapement design for the clock, the escapement being the mechanism that regulates and drives the pendulum, but which must be as disconnected as possible from the mechanism. At nearly the last minute, Denison substituted a new escapement of his own design, called a “double three-legged gravity escapement.” I will not attempt to explain its operation here, but I can show it to you (fourth image) and connect you to a Wikipedia animation that provides a start of an explanation. It was a great success, and soon all tower clocks were using Denison’s escapement, which he did not bother to patent. Finally, a diagram that shows the relative positions of the mechanism, the pendulum, the driving weights, and the escapement, might be helpful (fifth image).

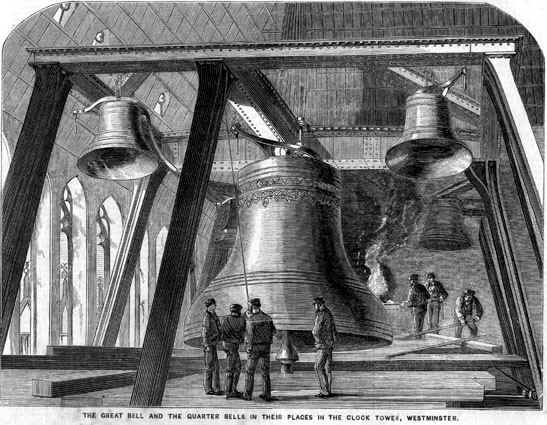

Denison was also in charge of choosing the composition of and casting the bells – the large hour bell, which came to be called Big Ben, and the four quarter bells for the quarter hours. The first large bell cracked and was recast, and the second one cracked as well, but was salvaged and placed in use. It weighs about 15 American tons. The tower clock was inaugurated on May 1, 1859. Denison even wrote the music played by the quarter bells, a ditty called the Westminster quarters, which you have certainly heard many times. Here is an audio file to remind you.

The original clock mechanism designed by Denison and built by Dent and Dent junior still drives the Big Ben clock, although it has been refurbished several times, once quite recently, which is not surprising, given the mechanical abuse it suffers every day. In 2012, the clock tower was renamed Elizabeth Tower. The clock is regulated by putting pennies on the pendulum, or taking them off, which raises or lowers the center of gravity a fraction, and adds or subtracts less than a second per day. This too was a Denison design feature.

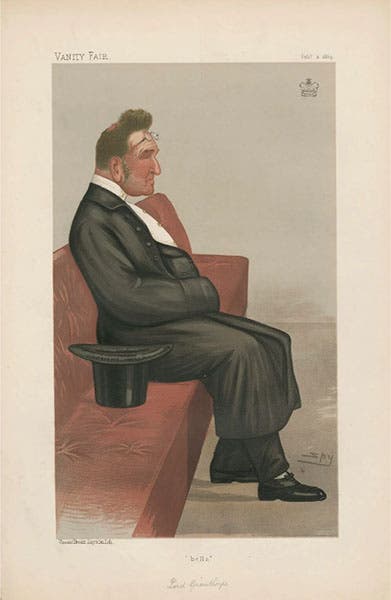

Denison went on to design other clocks, and buildings, and became First Baron Grimthorpe in 1886, at which point he dropped his surname Denison and became Edmund Beckett. He was caricatured by Leslie Ward (“Spy”) in Vanity Fair in 1889 (seventh image). The caricature has the caption: “Bells.” We once wrote a post on Ward, in which we showed 6 of his caricatures of scientists such as Richard Owen and Willam Huggins. The sketch of Lord Grimthorpe would seem to be a worthy addition to the group.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.