Scientist of the Day - Johann Ludwig Burckhardt

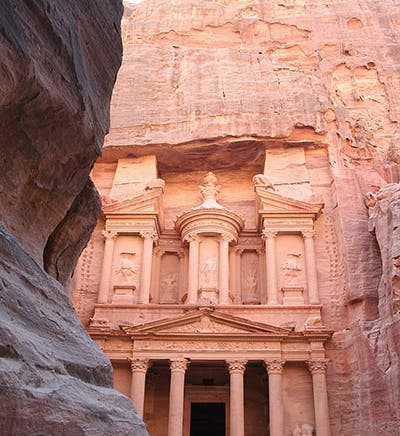

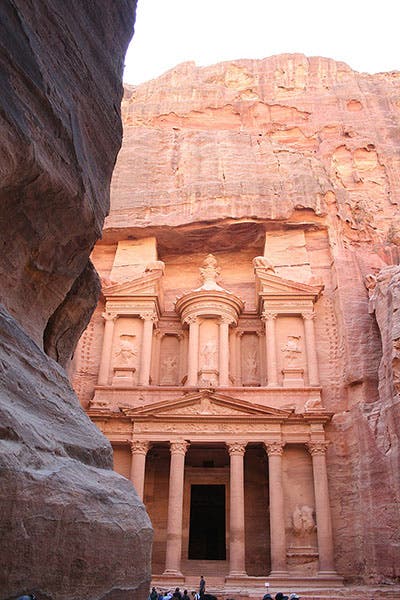

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss adventurer and explorer, was born Nov. 24, 1784, in Lausanne. On this day, Aug. 22, 1812, at the age of 27, he walked out of a narrow passageway in southern Jordan, and became the first Western European to set eyes on the temples and tombs, cut out of solid rock, that make Petra one of the wonders of the ancient world.

Burckhardt got to Petra by a circuitous route through life. Son of a wealthy Swiss silk merchant, he was educated at the best German universities and apparently never suffered from lack of funds. But then, he never needed much. He moved to England when he was about 22, looking for interesting employment, and he somehow encountered the African Association, founded in 1788 and headed up by Joseph Banks, the members of which were looking for intrepid young explorers to journey to and locate the Niger River and its most illustrious but unseen city, Timbuktu. They had sponsored quite a few explorers in their first 20 years, but nearly all had been murdered by thieves or had died of dysentery, including the most successful of them all, Mungo Park, who made it back from one expedition, but perished on the second. We have written about Mungo Park.

The Association decided that future explorers, to avoid being murdered en route, needed to be able to pass as Arabs. Burckhardt studied Arabic and Islamic culture and eventually moved to Aleppo in Syria, where he took an Arabic name and lived as an Arab for several years. It was while journeying to Cairo to look for a caravan to Timbuktu that he stumbled across Petra, which he recognized from ancient Roman accounts of Arabia Petraea.

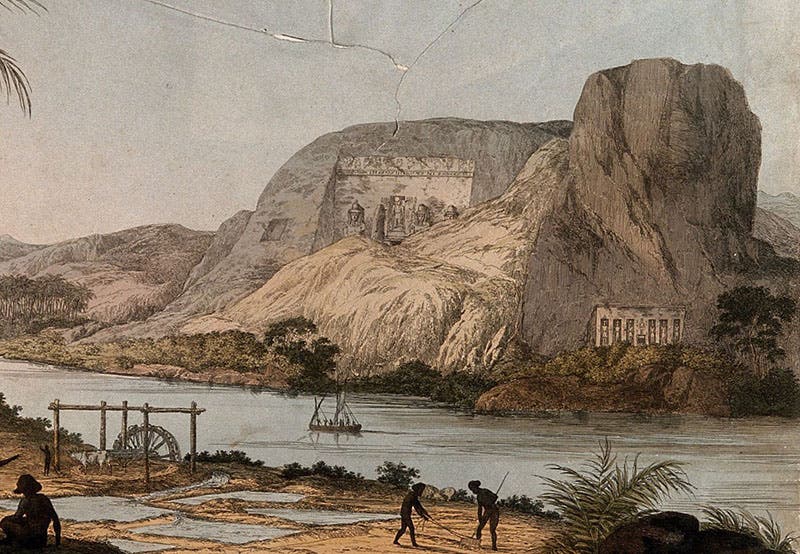

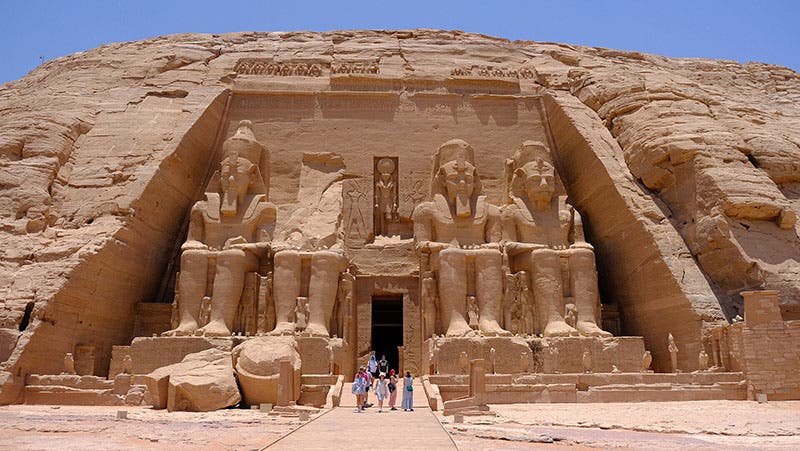

Burckhardt finally made it to Cairo but could not find a caravan west that he could hook up with, so he journeyed up the Nile (by donkey!), past Philae, at the first cataract, up toward the second cataract, near the border with Nubia. Here he was deterred by locals, but on the way back, on Mar. 22, 1813, he climbed down to a small temple on the west bank of the Nile, and saw, just to the south, a much larger temple almost completely buried in sand, with the head of one monumental statue (of four) poking above the dunes. Burckhardt had discovered the temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel.

He was unable to dig his way in, but when he got back to Cairo, he told Giovanni Belzoni about his discovery. Belzoni promptly made his own trip to Abu Simbel and he too was unable to defeat the blowing sand, but several years later, he returned with a larger crew and managed to dig his way into the hypostyle hall. Belzoni made a drawing of the partially excavated temple, which was engraved in 1820 (fifth image). Incidentally, Burckhardt was the one who introduced Belzoni to the English consul in Cairo, Henry Salt, who hired Belzoni to haul a fallen colossus known as the Younger Memnon from the plains of Thebes to the British Museum in London, a story we have told several times (see our posts on Belzoni and Percy Bysshe Shelley). Both temples at Abu Simbel have since been relocated to higher ground (215 feet higher!) to escape the rising waters of Lake Nasser after the building of the Aswan Dam.

So within the space of exactly 7 months, Burckhardt had discovered two majestic ancient sites, Petra and Abu Simbel. Unfortunately, his archaeological career was just about over. He remained in Cairo, and while waiting for his caravan to Timbuktu (I don't know what the problem was), he worked on perfecting his Arab disguise, even making a hajj to Mecca, a very difficult feat for a European to pull off, but he did. He also wrote up accounts of his travels, three of them, about trekking through Syria, Arabia, and Nubia, and sent the manuscripts back to his employer, the African Association, in London. This was fortunate, because he soon came down with his third case of dysentery, and died on Oct. 15, 1817, just 32 years old. He never got to make that trek to Timbuktu, for which he had prepared so thoroughly.

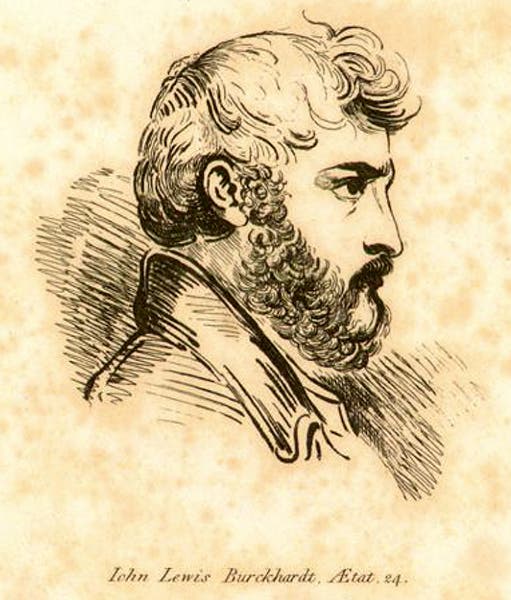

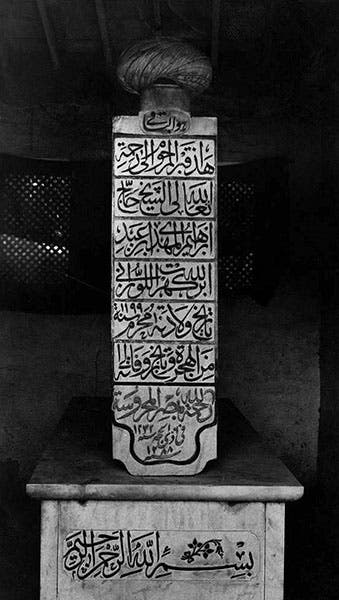

The African Association dutifully published all three of Burckhart's Travels (in 1819, 1822, and 1829; the first, Travels to Nubia, had a frontispiece portrait, our second image). They anglicized his name to John Lewis Burckhardt, and the books supposedly influenced later explorers to the African interior, such as Richard Burton. We do not own any of Burckhardt's publications, as they are a bit out of scope for a science library. The exact site of Burckhardt’s tomb is unknown, but there is a stele inscribed in Arabic that was put in place near the suspected location of his grave sometime in the 1850s (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.