Scientist of the Day - Louis Lartet

Louis Lartet, a French archaeologist, was born in the Pyrenees of France on Dec. 18, 1840. He was the son of Edouard Lartet, an archaeologist who first established the reality of prehistoric art in southwestern France in the 1860s, especially with his discovery of the Mammoth of La Madeleine in 1864. This exquisite artifact, carved from a piece of mammoth tusk, demonstrated not only that prehistoric peoples of France made art, but they made beautiful art. You can see the Mammoth of La Madeleine, and several other examples of Paleolithic art, at our post on Edouard Lartet.

Edouard, however, never discovered any fossil evidence of the people who carved those ancient artifacts. That was left to his son Louis, who was 28 years old when a rock shelter was discovered in Les Eyzies, along the Vézère River, in the Dordogne region of Fance. The rock shelter was called Cro-Magnon, and Louis was assigned to excavate the cave, which he did in 1868.

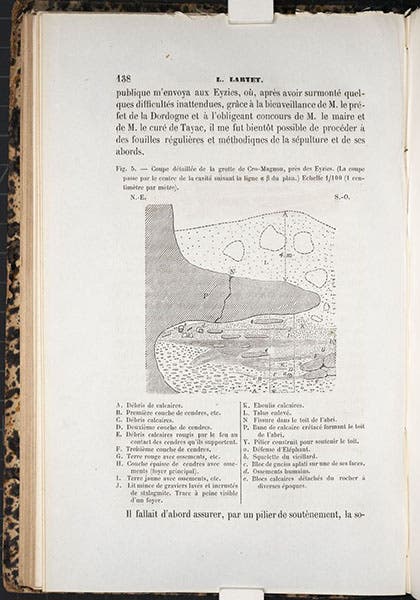

Page containing a diagram of the Cro-Magnon rock shelter at Les Eyzies with a detailed caption beneath, “Memoire sur une sepultre des anciens troglodytes de Perigord," by Louis Lartet, Annales des sciences naturelles, 5th ser., Zoologie et Paleontologie, 1868, vol. 10, p. 138, 1868 (Linda Hall Library)

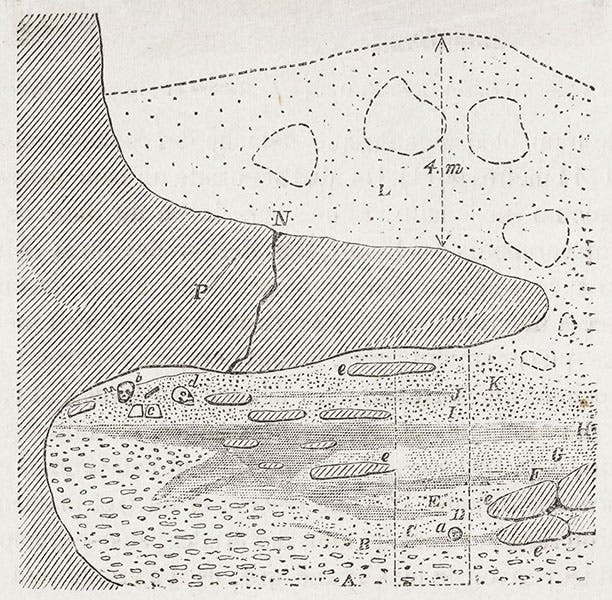

The cave was completely filled with rocky debris, as you can see from the diagram published in Lartet’s subsequent paper (third and fourth images). Digging it all out, Louis found the skeletons of five humans, four adults and an infant. The most complete specimen, of an old man, later called Cro-Magnon 1, was tall and capable of walking fully erect. He had a skull that was indistinguishable in structure from a modern human skull, with a high forehead, flat face, and minimal brow ridges. The only other well-established prehistoric human type was that of Neanderthal man (first found in 1856), who had a sloping forehead and face and prominent brow ridges, and whose post-cranial skeleton was much more robust (see our posts on Johann Carl Fuhlrott and Hermann Schaaffhausen, the discoverers of Neanderthal man). The remains at Cro-Magnon were different, and for many, more pleasing, and more suitable for a possible human ancestor.

Diagram of the Cro-Magnon rock shelter at Les Eyzies; the skulls at “b” and “d” mark the location of the skeletons, “Memoire sur une sepultre des anciens troglodytes de Perigord," by Louis Lartet, Annales des sciences naturelles, 5th ser., Zoologie et Paleontologie, 1868, vol. 10, p. 138, 1868 (Linda Hall Library)

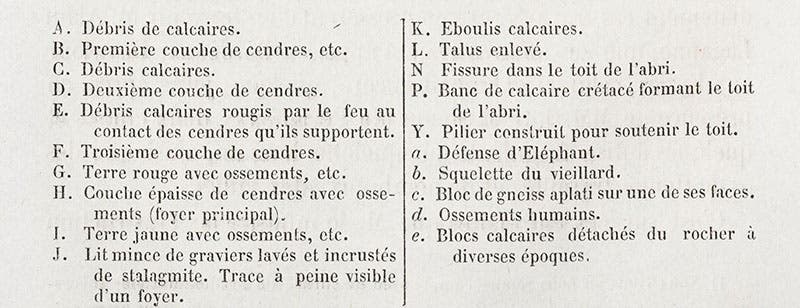

Lartet announced his discovery later that spring in a paper that he delivered to the Society of Anthropology on this day, May 21, 1868, and then published as (in translation): “Memoir on a gravesite of ancient cave dwellers of Perigord,” in Annales des sciences naturelles, a journal that we have in our serial collections at the library. In addition to the diagram of a section of the rock shelter (which we also show in detail in our fourth image), it has a well-drawn lithograph of the skull of “the vieillard,” the old man, Cro-Magnon 1 (first image). In the caption to the diagram (fifth image), you can see that the “squelette du vieillard” is denoted by the letter “b”, which you can find on the diagram at far left, just under the rock ledge, near the other skeletons at “d”.

Caption for the diagram of the Cro-Magnon rock shelter at Les Eyzies; the skeletons are referenced by “b” and “d”, “Memoire sur une sepultre des anciens troglodytes de Perigord," by Louis Lartet, Annales des sciences naturelles, 5th ser., Zoologie et Paleontologie, 1868, vol. 10, p. 138, 1868 (Linda Hall Library)

Cro-Magnon became better known when Edouard Lartet published (posthumously) his sumptuous Reliquiae Aquitanicae in 1875, which has a different (and tinted) lithograph of the Cro-Magnon 1 skull. You may see this illustration as the fourth image in our post on Edouard Lartet, and also in our exhibition catalog, Blade and Bone, which has an entry on Edouard’s Reliquiae, and on Louis’s paper as well.

A lot has been learned about the original Cro-Magnon specimens since Louis Lartet pulled them from the scree at the Cro-Magnon rock shelter in 1868. The best guide to that 160-year history is the thorough and always reliable webpage on Cro-Magnon at the anthropological website, Don’s Maps, which we have referred to many times, and upon whom I digressed at length in my post on Karel Absolon.

Louis Lartet had a less famous afterlife than Cro-Magnon 1, becoming professor of geology at Toulouse, and dying on an unknown day in August 1899, at the age of 58. He found several other Cro-Magnon burials in the 1870s, but never one quite as significant as the first one.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.