Scientist of the Day - Saint Dominic

Dominic de Guzmán, a Catholic priest, was born in Castile in 1170 and died on this day, Aug. 6, 1221, in Bologna, at the age of 50. Dominic was not a scientist but an ascetic mendicant monk, so we use his anniversary to talk about the order he founded in 1225, the Order of Preachers or, as it is more commonly known, the Dominicans, and the natural philosophers who belonged to that order.

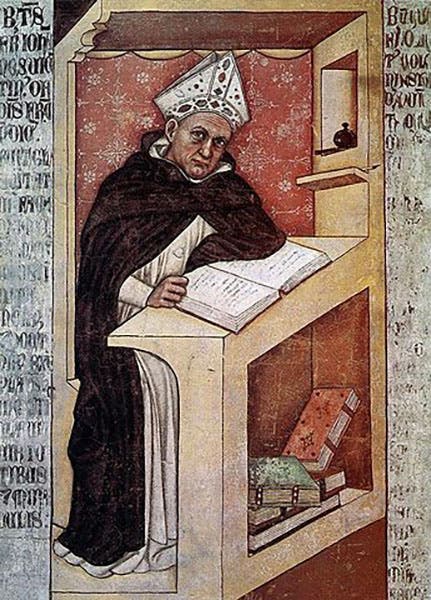

It is not clear why the Dominican order produced any scientists at all, but they did, and they began doing so right away. The two most influential natural philosophers of the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus, were both Dominicans. Thomas (second image) turned Aristotle into a Christian philosopher, a neat trick, and founded scholasticism; Albert (third image) was hands down the most gifted commentator on the natural world since Aristotle. I have written posts on both men, but in my piece on Albert I somehow managed not to mention that he was a Dominican, an omission I will correct as soon as possible.

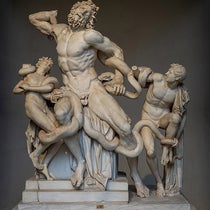

Another notable Dominican philosopher was one the Order would just as soon forget, although perhaps they are proud of him now, 425 years after he was burned at the stake in the Campo de’ Fiori in Florence. I speak of Giordano Bruno, of course, who was only a Dominican for 11 years, until he was 26, after which he was a lapsed Dominican. As an early and vocal Copernican, and an advocate for a plurality of worlds, he showed an independence of spirit and an originality of mind that cost him his life, and also made it difficult for others who were partial to Copernican cosmology. There is no surviving portrait of Bruno, but there is a statue with a face in Rome, on the site of his execution, which you can see in our post on Bruno.

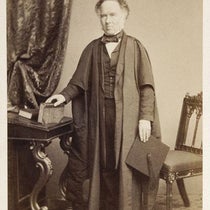

Bruno came from the Kingdom of Naples, and so did another Dominican philosopher, Tommaso Campanella (fourth image), who also got into trouble with the Inquisition, this time the Spanish version (Naples was ruled by Spain) and spent 27 years in prison, but managed to write (and publish) several treatises while confined, including a defense of (apology for) Galileo (1622). Campanella also published a utopian work, City of the Sun (written 1602; published 1623), an act that was guaranteed to keep him in trouble with ecclesiastical authorities. We have one Campanella work (but not either of these) in our collections.

One of the most talented Dominicans was not a scientist but a painter, Fra Angelico, who was an unassuming member of the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence. Cosimo de' Medici had evicted the previous friars at the convent and installed the Dominicans; he had the convent redesigned by the architect Michelozzo, working in the new Florentine style of Filippo Brunelleschi, and who should show up but Fra Angelico to decorate the cells of all the monks, plus the chapel, stairwells, and refectory, with his exquisite religious paintings, done in linear perspective, again following Brunelleschi. I have always wanted to write a piece on Fra Angelico, but I really cannot find a science connection, except for his use of perspective. Nevertheless, we include one painting here, his Annunciation (fifth image), as well as his portrait of Thomas Aquinas (second image), part of a larger fresco, removed from the wall at San Marco and now in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg (first image at our post on Thomas),

Someday I will certainly write a full post on Ignazio Danti, a Dominican friar whose scientific credentials are impeccable (sixth image). Working out of San Marco for a different Medici, a century after Fra Angelico, Danti painted 57 Ptolemaic maps on wood for a geographical salon in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. He also translated Euclid, and wrote a treatise on the astrolabe, editions of both of which we have in our collections, and mounted a meridian in the cathedal in Bologna. The only date we have for Danti is his death date of Oct. 19. Perhaps he can be our Scientist of the Day the next time that date rolls around. He will be our 6th Dominican to be so honored (if we count Dominic).

Finally, we can't help but point out that several Dominican churches besides San Marco have played significant roles in the history of science. Santa Maria Novella still displays a fresco by Masaccio (ca 1428) that is the oldest surviving painting exhibiting true one-point perspective, which you can see at our post on Masaccio. The facade of that same church was designed by Leon Battista Alberti and was the first Renaissance design based on Vitruvian principles and Pythagorean ratios (seventh image).

The church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, a Dominican church next to the Pantheon in Rome, was the site of Galileo's trial in 1633 (eighth image). And let us not forget the Dominican church of Santa Marie delle Grazie in Milan (ninth image). When they wanted to decorate the dining hall (refectory) of the convent with a suitable painting, they invited a local artist to have a go at the dining-room wall. The artist, Leonardo da Vinci, obliged with The Last Supper. We almost lost it during the War, but it somehow survived, perhaps the most enduring of all the Dominican gifts to the world.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.