Black Monday, 1652

Wilmari Claasen and Olivia Lanni (University of Zurich)

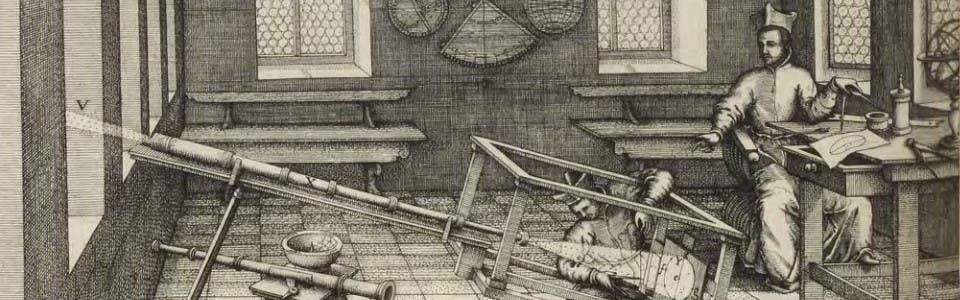

Eclipses fascinated people from all walks of life. Ordinary men and women had their own ways of interpreting these and other astronomical events. Eclipse images appear on the title pages of works like Nicholas Culpeper’s Catastrophe Magnatum, or, The Fall of Monarchie, and William Lilly’s Annus Tenebrosus, or the Dark Year. Culpeper and Lilly were astronomers, and their publications discuss the solar eclipse of 1652, visible over the British Isles, and popularly known as “Black Monday.”

Both works offer insights into contemporary cultural anxieties surrounding the cosmos. Culpeper’s text sheds light on the origins of these fears, noting:

the Sun is the light and governor of the world; a creature which gives life, light, and motion to the creation: by moving about his own body upon his Axis, he moves the whole creation.

The Sun is not only considered the origin and driving force of all life but to be representative of the monarch. The disappearance of the Sun was believed, therefore, to lead to horrors such as “violent storms” and “a consuming pestilence, and troubles, with a change of Government at one at the same time” in the following year. Beyond broader political issues, eclipses were believed to negatively affect the individual’s health. In the case of pregnancy, for instance, eclipses could cause deformities in the unborn child, producing “monstrous births,” a belief reaching back to antiquity.

Considering the vagueness of Culpeper’s and Lilly’s dire warnings, it only took a week for an anonymous pamphlet excoriating the two authors to start being circulated: Black Monday turn’d white, or, The astrologers knavery epitomized: being an answer to the great prognosticks and gross predictions of Mr. Lillie, Mr. Culpeper, and the rest of the society of astrologers concerning the eclipse of the sun on Munday […]. Despite the anonymity of the pamphlet, it represented an active public stance by expert astronomers and mathematicians in the field disputing popular superstitions.