Scientist of the Day - Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi, an Italian naturalist, was born Feb. 18, 1626. Redi was a physician at the Medici court in Florence and a member of the Accademia del Cimento, one of the world's first scientific societies. He is known for a set of experiments that he performed in the 1660s. Wondering where the worms came from in some snake meat that he had left lying about, he carefully followed the worms through their entire life cycles, from worms to pupae to flies. He surmised that perhaps flies laid the eggs that produced the worms. To test this premise (because, as he put it, "belief would be vain without the confirmation of experiment"), he took four flasks, and in each of them he placed, quoting his narrative, "a snake, some fish, some eels of the Arno, and a slice of milk-fed veal." He sealed the flasks up tight. Then he placed the same delectable morsels in another set of flasks, which he left open to the air. Sure enough, the sealed flasks produced no worms, while the open flasks bred worms aplenty. He concluded that his premise was correct: worms are produced from eggs laid by flies, and they do not generate spontaneously in putrid meat, as almost everyone else believed at the time. If you keep flies away from meat, if will never generate insects, not matter how rancid it gets.

Redi’s experiments are notable for many reasons, not least because they were among the first to utilize a set of controls (i.e., the set of sealed flasks) for verifying the conclusions. The account appeared in Redi's Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti (Experiments concerning the generation of insects, 1668), which we have in our History of Science Collection, and from which all the images today were taken.

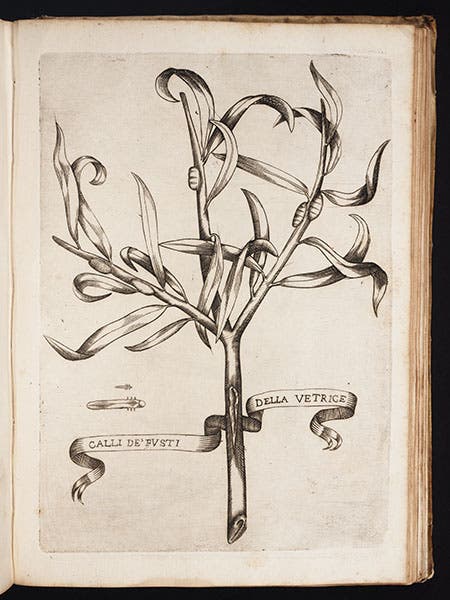

While Redi's experiments on meat and flies are discussed in nearly every biology textbook, it is often forgotten that, in the same book, he examined the question of the origin of the wasps and flies that emerge from galls on the leaves of various trees such as oaks, willows, and mulberrys. Here Redi was quite open to the possibility that the insects were produced by the trees. This seems inconsistent with his earlier stance, until one realizes that trees are living things, and producing life from life is quite a different matter than generating life from a non-living substance. At least it seemed different to Redi.

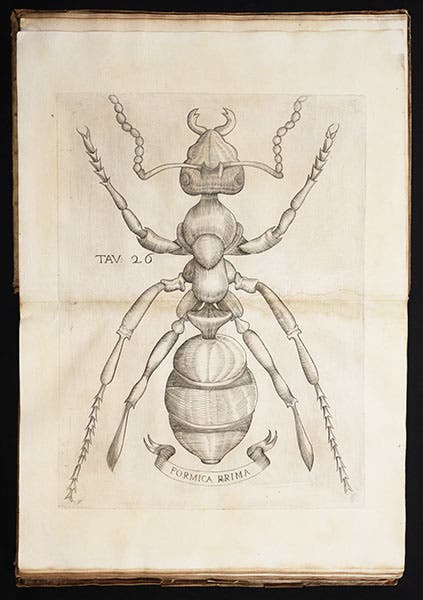

Oddly, there is no illustration of the eight-flasks experiment in Esperienze. But there are many other etchings, most of them showing insects as viewed through a microscope, and several that show galls on plants. We show here illustrations of a weevil, two lice, an ant, and a plant decorated with galls.

One should remember that it had been only three years since Robert Hooke in his Micrographia (1665) had given the world its first printed images of magnified mites, lice, and fleas, so Redi's etchings were eye-openers to many of his readers.

We also show the title page of Redi’s book, which sports an engraved vignette that depicts the motto of the Accademia della Crusca on a banner: Il più bel fior ne coglie (she gathers its fairest flower), while the image makes a visual pun from the fact that fior can mean flower or flour.

Redi's Esperienze was enlarged and republished in 1688, with additional plates, and the modern English translation (1909) is based on the later edition, not the first, should you want to read about Redi's experiments in his own words. We have both editions, and the translation, in our collections.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)