Scientist of the Day - Henry Baker

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

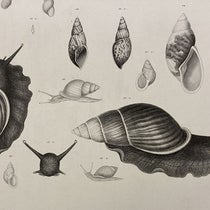

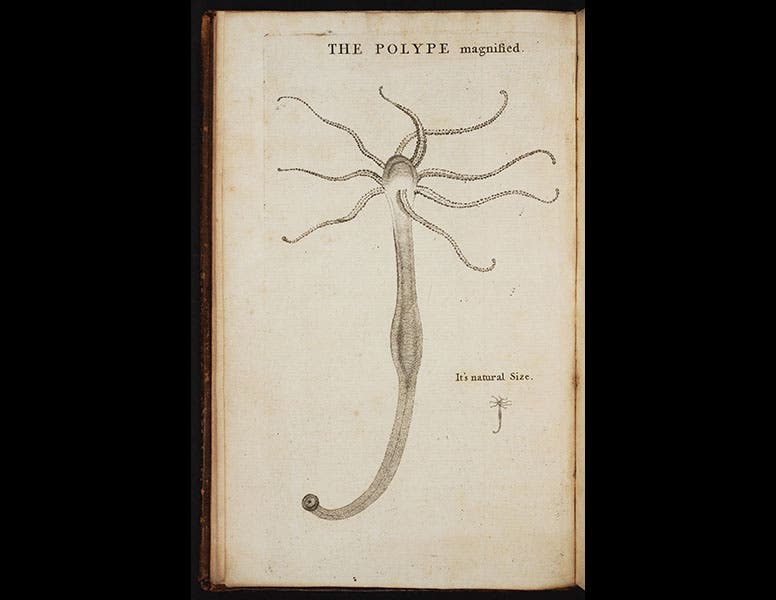

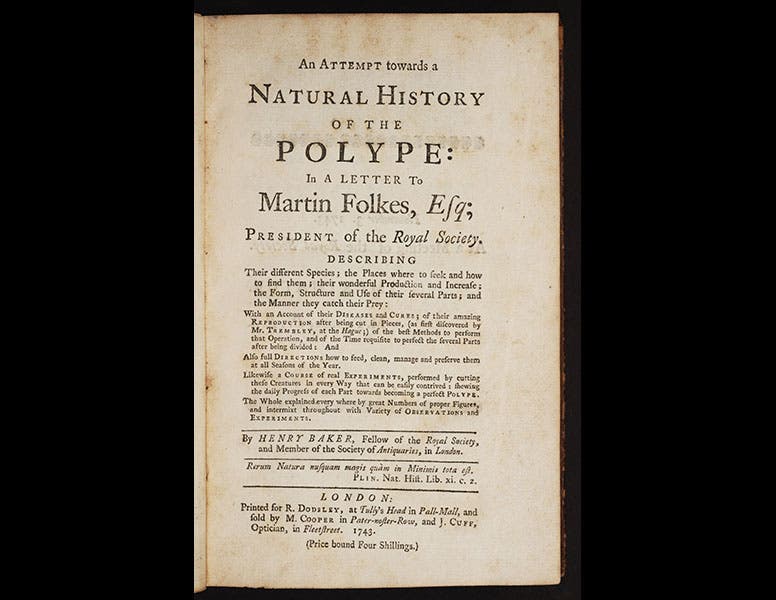

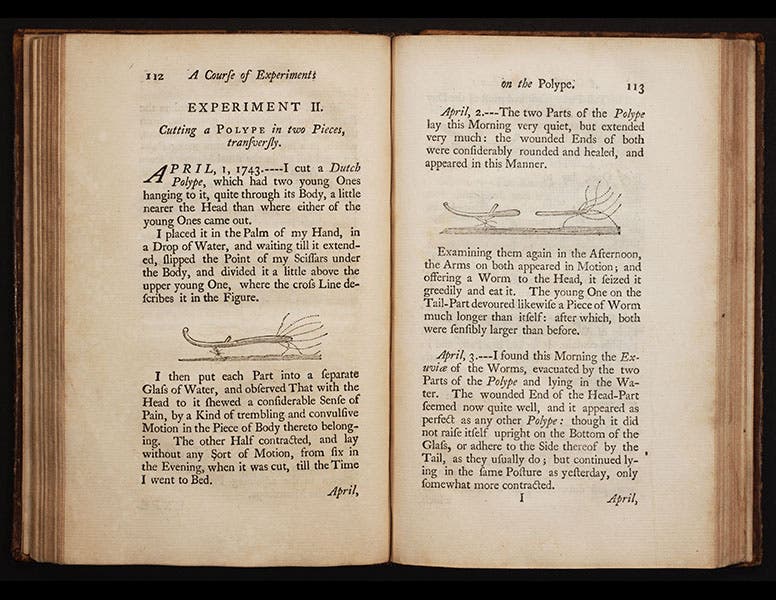

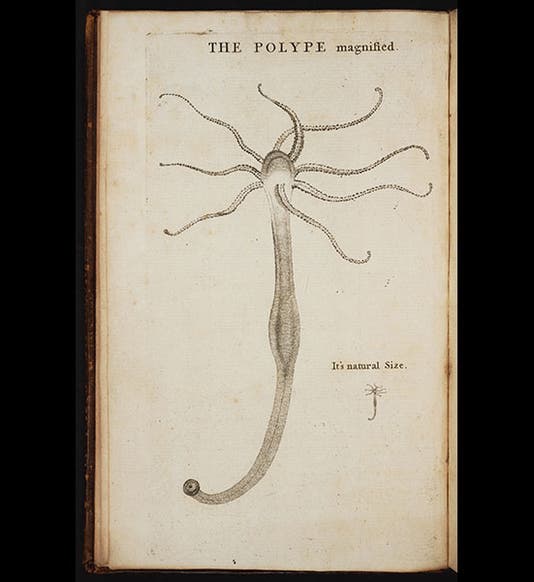

Henry Baker, an English microscopist, was born May 8, 1698. In 1740, a French naturalist, Abraham Trembley, had discovered that hydra (tiny organisms found in pond water, also called polyps), have astonishing regenerative powers. Cut them in half, crosswise or lengthwise, and the remaining half grows back, good as new. Most naturalists would have found this unbelievable at the time, so Trembley cleverly sent samples of his little beasties to many of the scientific societies of Europe, so that others could try the experiments for themselves. Baker latched onto the specimens that were sent to the Royal Society in London; he received the first one in the spring of 1743, and by November, he had a 220-page book ready for the press, An Attempt towards a Natural History of the Polype, and it beat Trembley’s own book into print by a full year. Baker gave Trembley credit for the discovery in his own book, but he still made a tidy penny from the sale of his work. We see above the frontispiece, showing a magnified polyp (first image), the title page, and a two-page spread, in which he illustrates the stages of regeneration after a polyp is cut in half (third image).

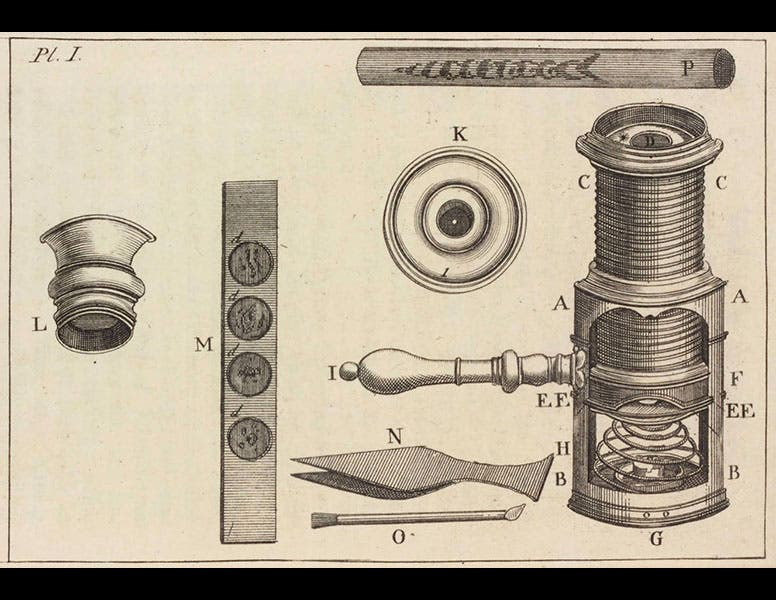

A year earlier, Baker had published The Microscope Made Easy (1742), a guide to using the microscope that must have filled another marketing niche, for it was followed by an enlarged edition the next year. In 2009, we displayed the 2nd edition of Microscope Made Easy (fourth image) in an exhibition about single-lens microscopes, Singular Beauty, open to the page where Baker illustrates a screw-barrel pocket microscope made by James Wilson (fifth image). Right next to it, we exhibited a real James Wilson screw-barrel microscope from the collection of Ray Giordano. It made for a very effective display.

When Baker died in 1774, he left £100 to the Royal Society to fund an annual lecture, which came to be called the Bakerian Lecture. It has been given more or less annually from 1775 to the present. One memorable Bakerian lecture was given by Ernest Rutherford in 1920, in which he announced the discovery of the proton and postulated the existence of the neutron, which would be discovered 12 years later. Not many lectureships can boast bombshells like that.

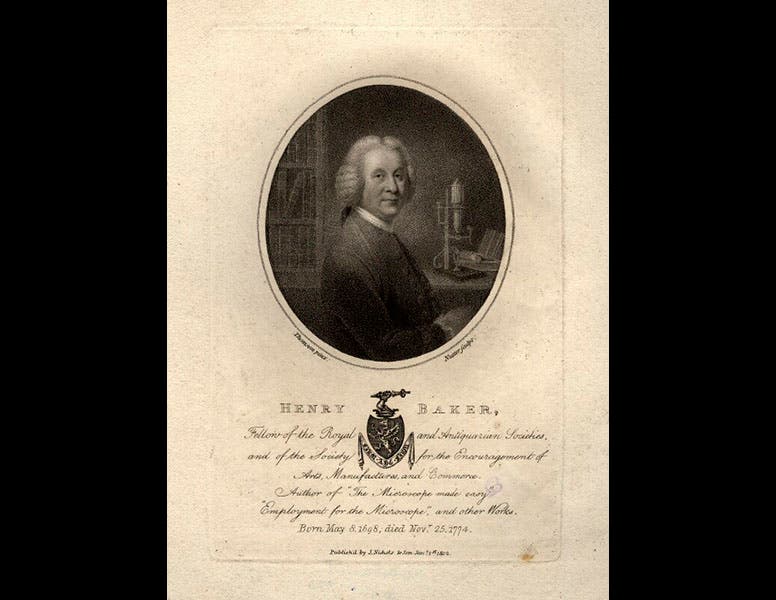

The engraved portait, made posthumously, is in the National Portrait Gallery, London (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)