Scientist of the Day - Pierre de Maupertuis

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

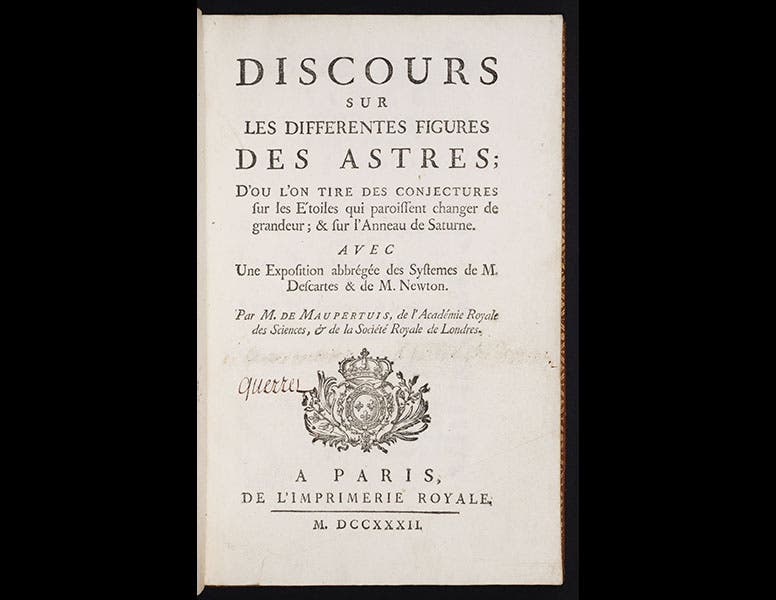

Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, a French mathematician and physicist, was born July 17, 1698. In 1732, Maupertuis published a slim treatise, Discours sur les differentes figures des astres (Discourse on the different figures of the stars, second image), in which he examined the Cartesian and Newtonian systems of the world. The French had always been partial to the vortex theory of planetary motion proposed by René Descartes, but by Maupertuis's time, Newtonian cosmology, founded on the principle of universal gravitation, was almost 50 years old, and it had been attracting more and more French followers, such as Voltaire. In his book of 1732, Maupertuis compared the two systems and found the Cartesian cosmology wanting, especially in its explanation of gravity. At the end of the book, Maupertuis added an eighth chapter in which he considered the nature of Saturn's ring and the phenomena of variable stars. Variable stars were a relatively recent discovery; only a handful were known, and explanations of their changes in brightness were not very satisfactory. Having just discussed (in chapter 6) the shape of fluid bodies rotating on their axes, Maupertuis realized that a rapidly rotating star might have a flattened shape, so that if it were observed from above, it would have its maximum brightness, but if observed edge-on (as with the ring of Saturn), the star might actually seem to disappear. He offered this as an explanation for variable stars.

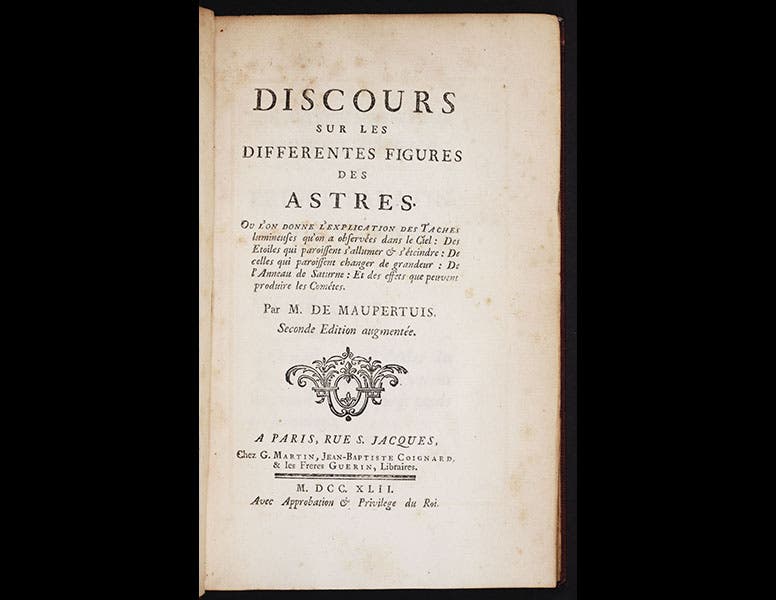

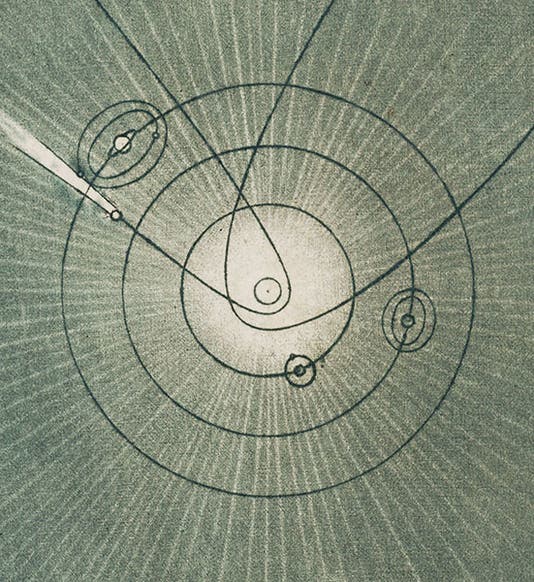

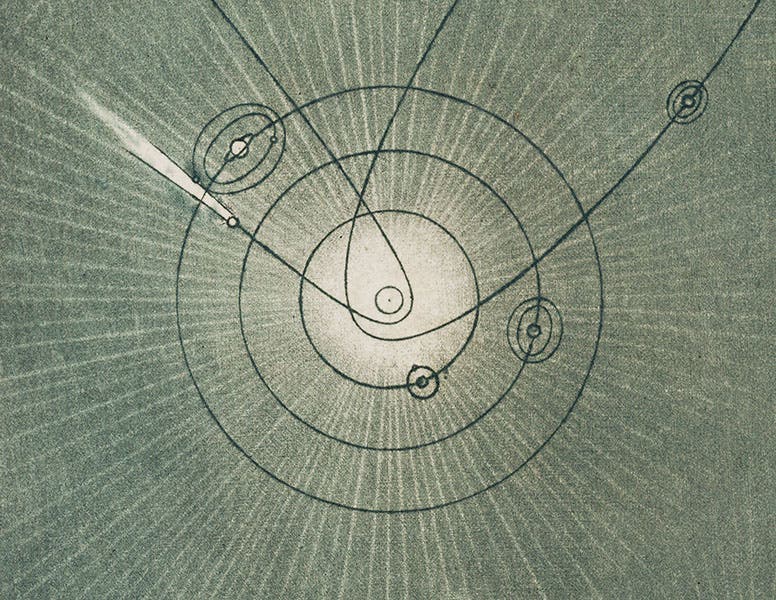

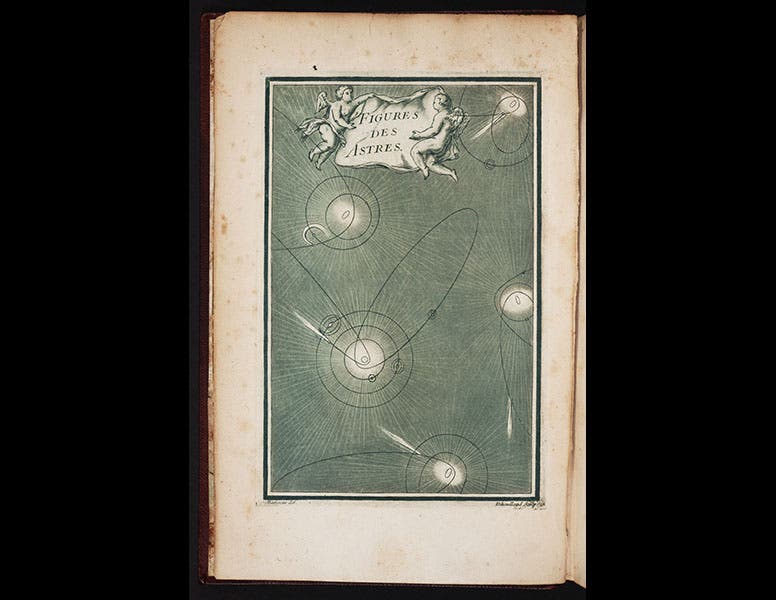

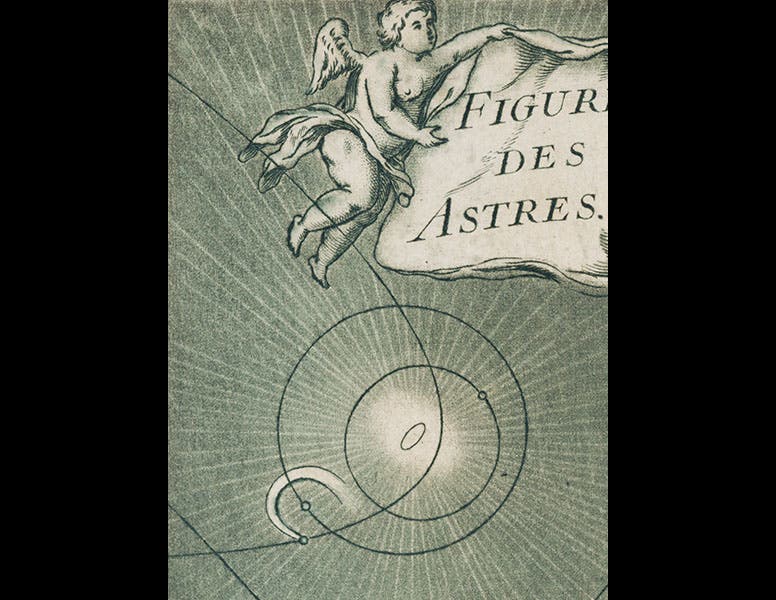

What makes this especially interesting is that, ten years later, Maupertuis published a second edition of his Discours (third image), by which time he was a thorough Newtonian and did not feel it necessary to give Descartes equal time. This edition is twice as long as the first, primarily because Maupertuis added four supplemental chapters in which he laid out all the mathematical proofs that were implicit in the first edition. The other difference between the two editions is evident as soon as you look at the title page, because sitting opposite is a colorful engraved frontispiece that does not appear in the first edition (fourth image). The engraving, titled "Figures des astres", depicts our solar system, with two comets, just below left-center (see detail, first image) and four other stars with their planetary systems. The Sun is round, but the other stars are oblate, in accord with Maupteruis's conclusion that rapidly rotating stars would flatten out. The fifth image shows a detail of the stellar system with its flattened star at upper left, along with part of the title cartouche.

This frontispiece is one of the most striking engravings of eighteenth-century science. It is, first of all, a mezzotint, meaning the entire copper plate was abraded by a rocker so that, if printed at that point, it would be solid black. Then certain areas of the plate were smoothed with a special tool to flatten the burrs, so that those areas would print white. Finally, the orbits of the orbits of the planets were added in with a conventional engraver's burin. In our copy, and (we understand) in some but not all other copies of the 1742 edition, the mezzotint was printed in green, before the stellar systems and title cartouche were printed in black. It makes for a most striking cosmos. If there is anything else like it in the realm of Enlightenment frontispieces, we don’t know about it. If you do, please let us know.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)