Scientist of the Day - Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn, a Dutch artist, was born July 15, 1606, in Leiden. Rembrandt, perhaps the greatest Dutch painter ever, was in no sense a scientist, but two of his most memorable paintings have a scientific subject matter. The first was a product of his early career. Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam as a young man, and soon after his arrival, he was commissioned to paint a group portrait centered on the new demonstrator of anatomy at the Guild of Surgeons, Nicolaes Tulp. The resulting painting (first image), executed in 1632, shows Tulp dissecting the forearm of a cadaver and revealing the tendons that work the fingers. Considerable scholarly ink has been devoted to the question of why Tulp is shown dissecting the arm first, when traditionally an academic dissection would begin with the abdomen, since the internal organs need to be dealt with and removed as soon as possible, even in January, when the dissection was traditionally performed. I will spare you the details of the debate, since no one really knows, and instead mention two facts that we do know for sure. One, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp hangs today in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, which was built by Johan Maurits while he was in Brazil setting up a Dutch colony in the late 1630s. You can see a photo of the painting on display here. Second, the painting depicts the interior of the old De Waag, or Weighhouse, where the Surgeons Guild was located; it used to be one of the Gates of Amsterdam, and today is a tourist attraction, with a café out front (here is a modern photo). So you can eat lunch not fifty feet from where they used to cut up criminals.

The other painting we would like to showcase is what used to be called Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer, and is now Aristotle with a bust of Homer, although it seems contemplative enough to me (second image). The painting is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and we would normally use the image on its website, but it is so dark that you can see few details (see for yourself), so we use a brighter version from Wikipedia instead. Art historians do not seem much bothered by the fact that Aristotle is portrayed in the garb of a wealthy Dutch burgher, perhaps because the figure of Aristotle, and especially the face, is so exquisitely painted. A medallion portrait of his famous pupil, Alexander the Great, hangs from the chain around his neck, which you can see if you click on the Wikimedia image to enlarge it. Rembrandt does not tell us that this is Aristotle, so that has been inferred, and some historians take issue with the identification, but most everyone else, including the Met, seems quite happy with it, even if they no longer think he is contemplating.

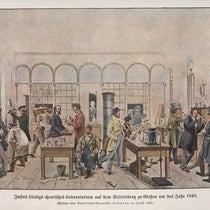

The Met also has a handsome self-portrait of Rembrandt, showing him at age 54, which you can see here. As many of you know, Rembrandt did scores of self-portraits, and they form a famous series because he was so frank and unsparing in his views of himself. We thought we would include one from near the time when he painted Dr. Tulp, because it showcases his other great talent – etching. Rembrandt was one of the great masters of etching as an art form, and his skill is evident an early age. This etched self-portrait is in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford (third image).

Just one week ago, we discussed another famous medical painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), by Thomas Eakins. It is instructive to compare early 17th-century Dutch and late 19th-century American painting styles, especially when wielded by two giants in the history of art. You can see our earlier post here.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)