Scientist of the Day - Archimedes

Archimedes was perhaps the greatest scientist, and certainly the greatest mathematician, of the ancient world, and it is surprising that we have written only a single post under his name in 11 years, but that is what happens in an anniversary series when a subject does not leave behind a birthday or death date or an anniversary of any kind.

We know very little about Archimedes the person. We know he was born outside Syracuse, in Sicily, which was then part of Magna Graecia and thoroughly Greek. We know he died in 212 BCE during the siege of Syracuse, led by Marcellus, a Roman general. Since one of the ancient commentators on Archimedes claimed that he was 75 years old when he died, we infer that he was born about 287 BCE. This would make him about 70 years younger than Euclid, and about 10 years older than Eratosthenes, the other two renowned mathematicians of early Hellenistic times. Both Euclid and Eratosthenes worked in Alexandria, the cultural center of the Hellenistic world, but there is no evidence that Archimedes ever went there. He did correspond with Eratosthenes, and dedicated a treatise to him, so they were probably mutually respectful of each other's work. There are no surviving portraits, coins or medallions with an image of Archimedes. His grave was discovered and described by Cicero, but it has not been seen since.

Fortunately for his legacy, Archimedes wrote books, treatises really, as they tend to be short and devoted to single subjects, such as On the Measurement of the Circle, or On the Sphere and the Cylinder, and all together, his surviving works fill only a single volume. But they do survive, because later mathematicians esteemed them and commented upon them regularly.

Archimedes was interested in mechanics, the science of machines, and in pure mathematics. For 18 centuries after his death, he was best known for his mechanics, but after Newton and Leibniz invented calculus in the late 17th century, and it was realized that Archimedes had essentially anticipated them, his mathematical genius has tended to be praised more than his mechanical ingenuity (except in secondary science textbooks).

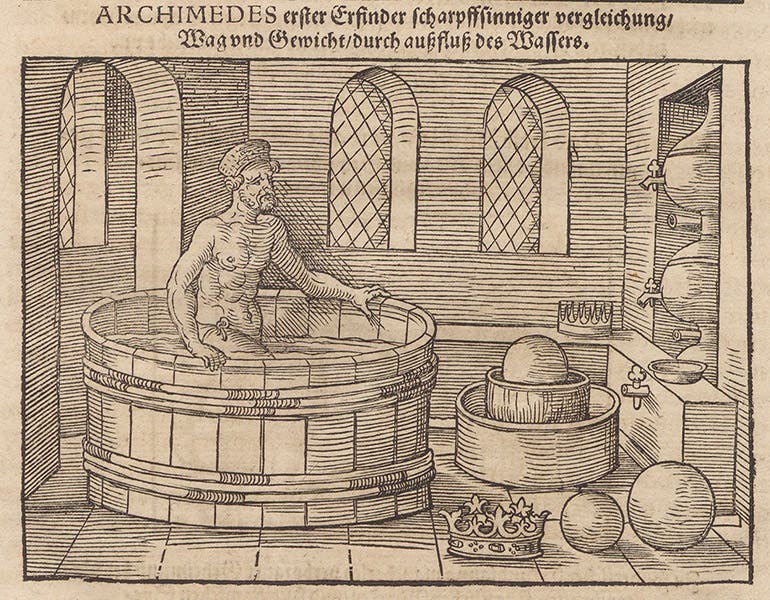

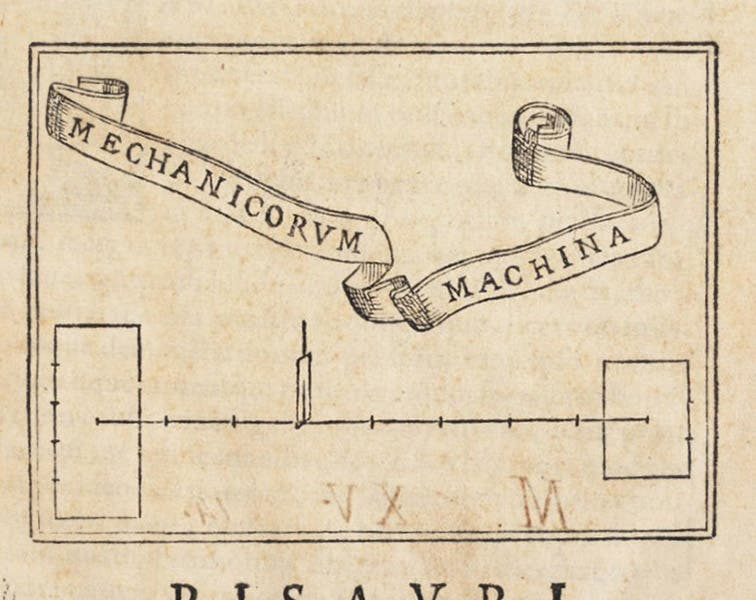

In mechanics, Archimedes discovered the law of the lever, which explains balances and mechanical advantage, and several principles of floating bodies, including one that states that a body immersed in water is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of water displaced. He did not invent the screw used to raise water in the ancient world, known everywhere as Archimedes' screw, but one can understand why later generations thought he did. And although he did apparently assemble several planetaria, he did not build the Antikythera mechanism, despite the claims of the latest Indiana Jones film.

In mathematics, Archimedes is best known for his method of exhaustion, which he applied in his book on measuring the circle. He found that he could approximate the circumference of a circle with an inscribed polygon, such as a hexagon, whose circumference can be known exactly, and that if one replaces the hexagon with an octagon or dodecagon, one can get a even better approximation. The key insight came next: if you let the number of sides of the inscribed polygon increase without limit, you can get as close you wish to the actual value of the circumference (and thus the value of pi). That is the method of exhaustion, and the underlying principle of differential calculus. Archimedes himself calculated that pi lies between 22/7 and 223/71, which puts it, by our notation, between 3.1408 and 3.1428, by far the best value anyone would have until the late 16th century.

Archimedes probably had his greatest impact on western science in the late 16th century, when all his available works were translated into Latin and published (see our post on Federico Commandino), and when Galileo decided to reject the qualitative physics of Aristotle in favor of the quantitative approach of Archimedes, and published his own Discourse on Floating Bodies, inspired by Archimedes' treatise on the same subject.

There are many stories involving Archimedes that have come down to us, such as the weighing of Hiero's crown (Eureka! Eureka!), and the tale of the burning mirrors, and the manner of his death – some possibly true, some unlikely, but all entertaining, even in their multiple variants. We will discuss some of these in a follow-up post soon.

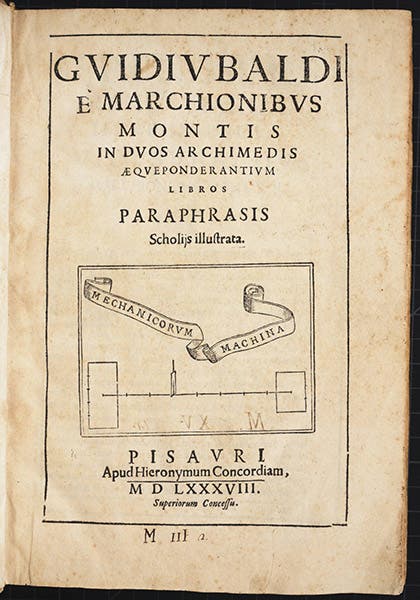

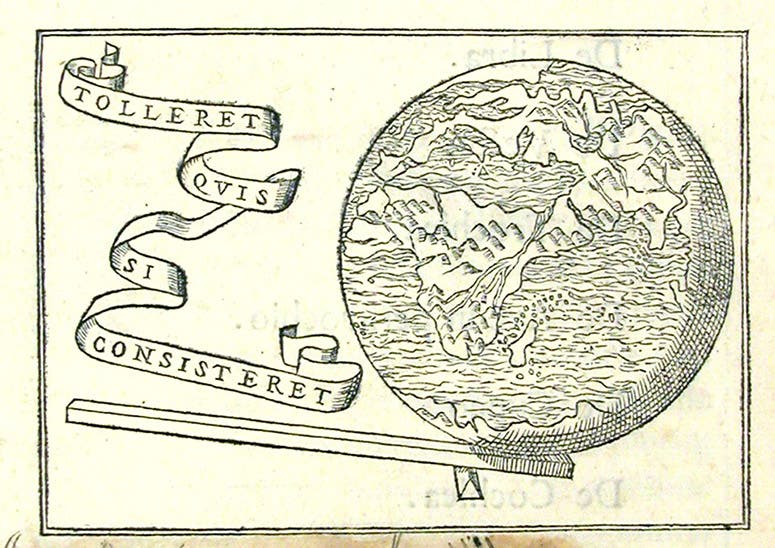

We have many editions of Archimedes’ works in our library, published in the last 500 years, and we illustrate today’s post with illustrations from a few of these, including a portrait that is not really a portrait, but is nevertheless special, since it adorns the first published work of Archimedes in the Renaissance (1503), his treatise on measuring the circle (first image). One work we do not have is an early edition of Archimedes’ treatise On Method, because it did not survive, or so it was thought. But in 1906, a palimpsest – a manuscript that has been written on, erased or scraped, and then rewritten upon – surfaced in Europe, and it contained, underneath some religious writing, the texts of many of Archimedes works, including the missing On Method. The palimpsest disappeared again, but resurfaced on the auction block at Christie’s in 1998, and was sold to a dot.com billionaire, and has since been thoroughly analyzed by the best available technology, to make visible the underlying Archimedean text. We told some of the story of the Archimedes palimpsest in an earlier post.

Portrait of Archimedes, engraving in Les vrais pourtrait & vies des hommes illustres, by André Thevet, vol 1, p 46, 1584, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison (photo by author)

My favorite portrait of Archimedes, one that at least looks plausible, even though it is not a true likeness, is an engraving in a portrait book we do not have in our collections: Les vrais pourtrait & vies des hommes illustres, by André Thevet (1584). I include it because I saw it many years ago in the University of Wisconsin Library in Madison, and snapped a photograph. Here it is, from Kodachrome to you (last image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.