Scientist of the Day - Richard A. Proctor

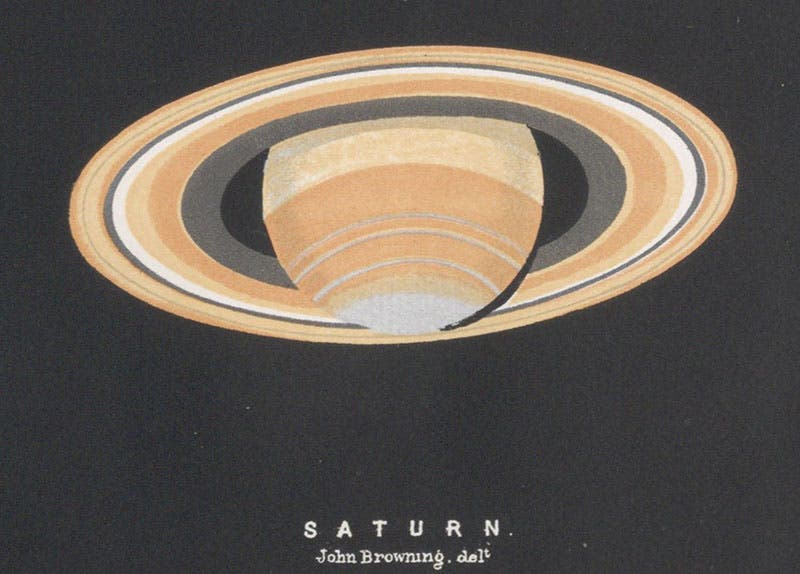

Richard Anthony Proctor, an English popular writer and astronomer, died Sep. 12, 1888, at the age of 51. Initially of independent means, he wrote his first book, Saturn and its Systems and published it himself in 1865. It is a lovely book, with its gold embossed covers and attractive plates of Saturn. In our first post on Proctor, our images were taken from a first edition of this work.

Saturn and its System did not sell particularly well, because it was aimed at too high a level. Proctor was not yet considered an astronomer and he had aspirations of such recognition, so he aimed his book at the professionals. Shortly thereafter, a bank collapse took care of his independent means, and he found he had to write for a living, for the general public. He figured out how to do that in very short order, publishing scores of titles over the next 20 years, all very entertaining and readable.

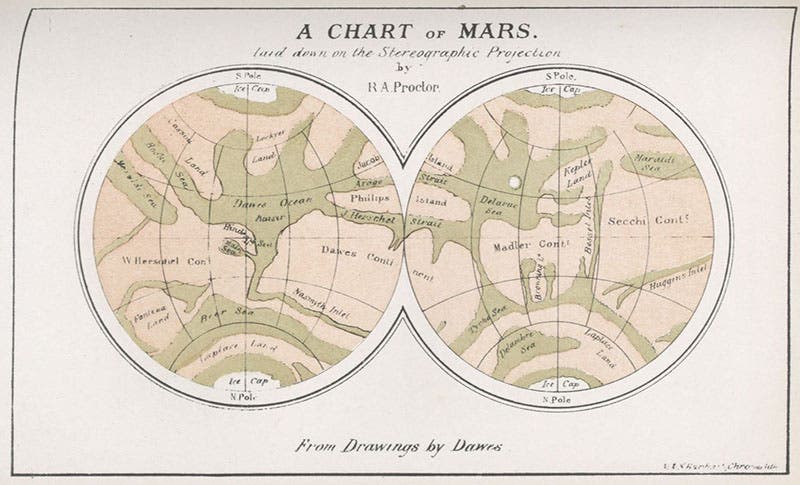

One of Proctor’s early interests was the planet Mars. Indeed, his first professional papers, published in 1867 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, concerned Mars’ daily rotation period, which he measured quite accurately. Around this same time, he saw some drawings made by William Rutter Dawes of the ruddy planet, and Proctor decided to turn those drawings into a map, with names that he himself would devise.

There was no agreement among astronomers about how to construct a proper planetary nomenclature. In the 17th century, when better telescopes provided an occasion for naming the features of the Moon, the first nomenclature system (that of Johannes Hevelius) was based on ancient earth geography, while an alternative system (that of Giambattsta Riccioli) derived lunar terms from the names of famous astronomers for the craters and meteorological terms for the “seas.” No one “decided” which one was better, but 100 years later, Riccioli’s system, based on the names of astronomers, was the one in use.

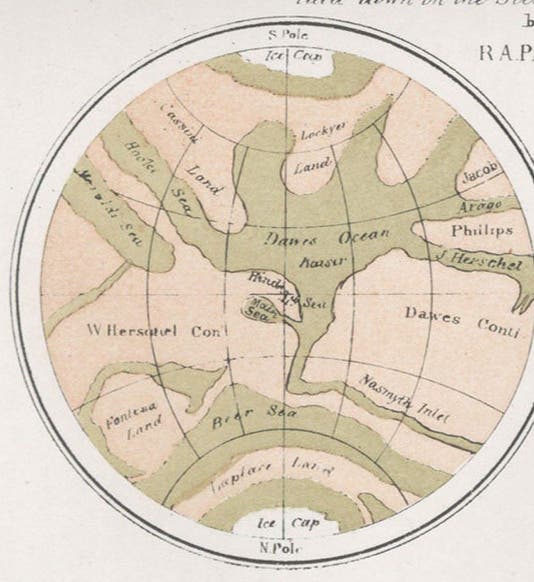

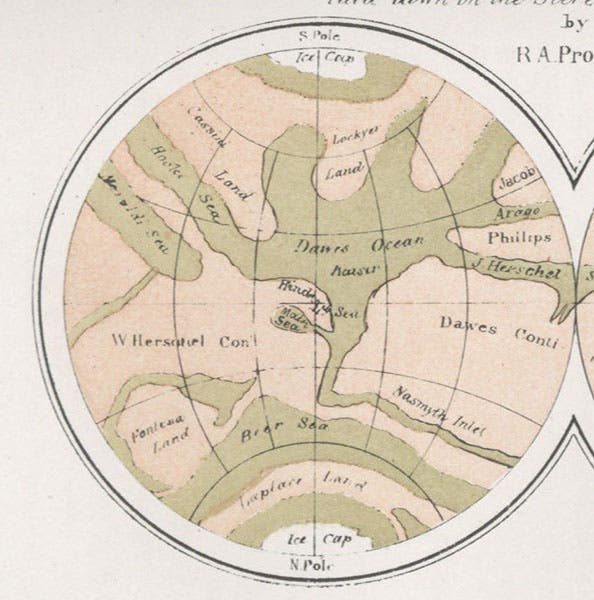

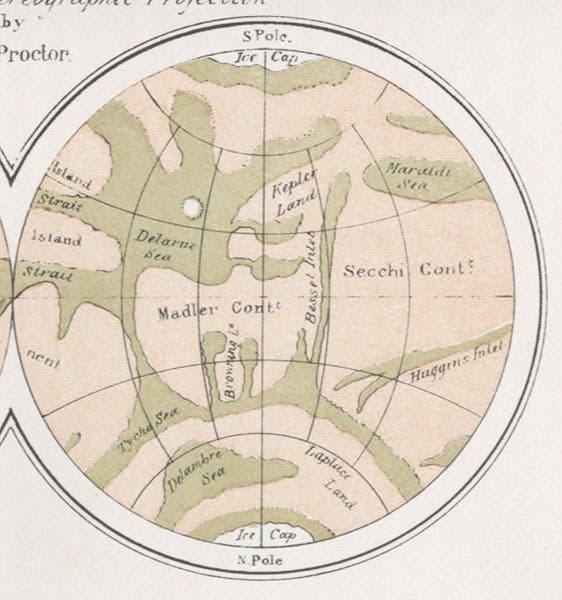

Proctor apparently took the past as his guide, for on his map, he named the features after astronomers, usually ones who had made some contribution to an understanding of Mars. He decided to call the light areas “land”, and the dark ones “seas,” and thus we had the Beer, Maedler, and Herschel Continents, the Dawes and De La Rue Oceans, and the Kaiser Sea, named after Wilhelm Beer, Johann Mädler, William Herschel, Warren de la Rue, Frederik Kaiser, and Dawes. You can see most of these names on the two details of Proctor’s map (first and sixth images).

When did Proctor’s map first appear? Everyone, and I mean everyone, agrees that he made his map in 1867. However, I have never seen an 1867 map reproduced anywhere, so I am skeptical. The first published version that I have traced appeared in 1870 in a new Proctor book called Other Worlds than Ours, published by Longmans Green. We do not have a first edition of this book in our collections, although we have been trying to acquire it, since we have an exhibition coming up on the plurality of worlds. But we do have an 1882 edition by the same publisher, in which the map (and the other images) appear to be identical to those in the first edition, which I compared online. And the plates in our 1882 edition are in pristine condition, with the solid black background unscratched by users, so it is for now, a happy substitute for the 1870 edition.

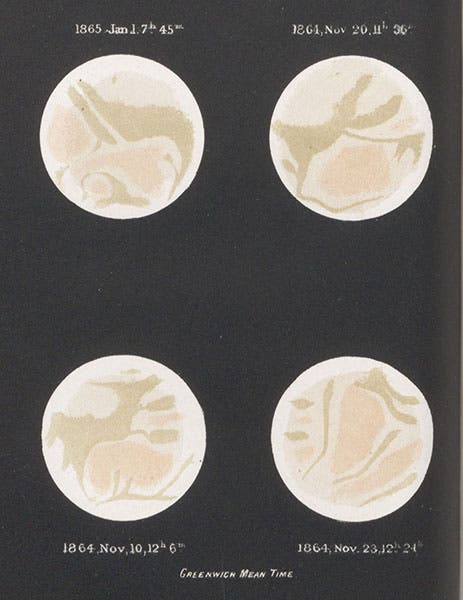

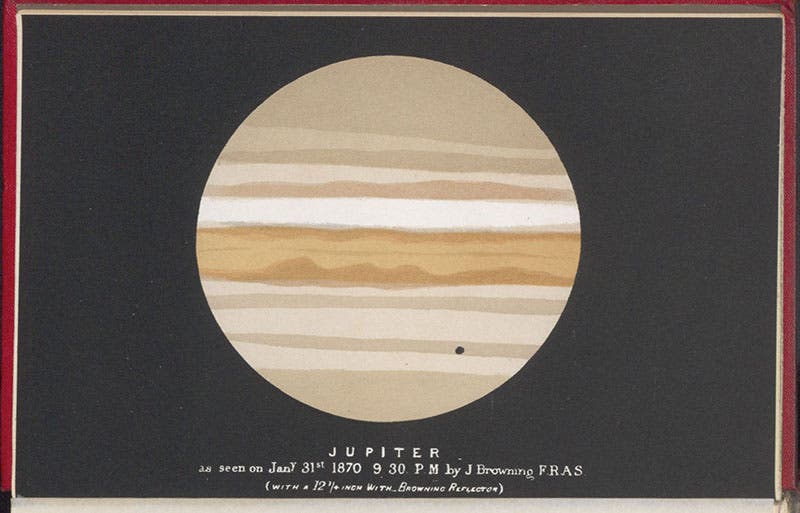

We show both hemispheres of Proctor’s Mars map in our fifth image. We also show four of the watercolors made by Dawes that Proctor used for his map (he says he used 26 Dawes drawings in all) (fourth image). There is also a splendid painting in the book by John Browning of Jupiter (seventh image), showing the shadow of one of its moons; which is dated 1870, so I don’t know if it was included in the first edition. There is one other painting by Browning included, depicting Saturn and its rings (eighth image). There had been an impressive plate of Saturn in Saturn and its Systems, which you can see at our first post on Proctor, but it doesn’t hold a candle to this one, which is so gloriously hand-colored.

Proctor’s nomenclature system for Mars was welcomed by Nathaniel Green, who made it the basis for a greatly expanded Mars map of 1879, which you can see in our post on Green. However, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, observing the same opposition of Mars in 1877 as Green, devised his own nomenclature system, basing it – you guessed it – on ancient earth geography, so he called that prominent India-like feature, which Proctor had named the Kaiser Sea, Syrtis Major, after the Roman name for the Gulf of Sidra in Libya. And Syrtis Major it is today. Green backed the favorite, but the favorite lost, as favorites often do.

Proctor spent his last years in the United States, where, in the mid-1880s, he was drawn into a caustic newspaper war with Edward Holden, director of the Lick Observatory, who had little use for amateurs who tried to work their way up to be professionals. We mentioned Holden obliquely in our post on James Keeler just two days ago.

We have some 30 books by Proctor in our collections. We would like to acquire that first edition of Other Worlds than Ours to make it a prime 31.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.