New Optical Technologies

Alessia Tami (University of Zurich)

The Camera Obscura

An invention that allowed individuals to observe the Sun without damage to the eyes was the camera obscura, derived from the Latin for “dark chamber.” A camera obscura can be made by using a darkened room or a box with only a small lens or a hole through which the light can filter. The light rays passing through the aperture will project an upside-down image of the outside object originally emitting or reflecting the light.

The Flemish mathematician and geographer Reiner Gemma Frisius used a camera obscura to observe the solar eclipse in Leuven, Belgium, on January 24, 1544.

Click here to learn more about Gemma Frisius.

The Telescope

The first telescopes were devised in the Netherlands in 1608. Hans Lipperhey, a German-Dutch lens grinder and eyeglass maker, was the first to submit a patent application for the spyglass, although many others had become aware of the basic optic mechanism necessary to make a telescope.

Click here to learn more about Hans Lipperhey

Galileo Galilei soon heard of the Dutch invention and set to work improving the telescope’s magnifying power. By November 1609, Galileo’s telescopes magnified an object up to twenty times instead of the original three. To achieve such results, Galileo taught himself how to make convex and concave lenses with the necessary focusing power.

The development of the telescope meant that sunspots could be observed with greater precision, along with the solar faculae, a brighter area sometimes surrounding sunspots. But observers of the Sun still faced considerable challenges. On account of the intense radiance and brilliance of the star, prolonged scrutiny with the naked eye was impossible unless viewers chose their timing carefully and waited for cloud cover.

Click here to learn more about Johannes Kepler.

The Helioscope

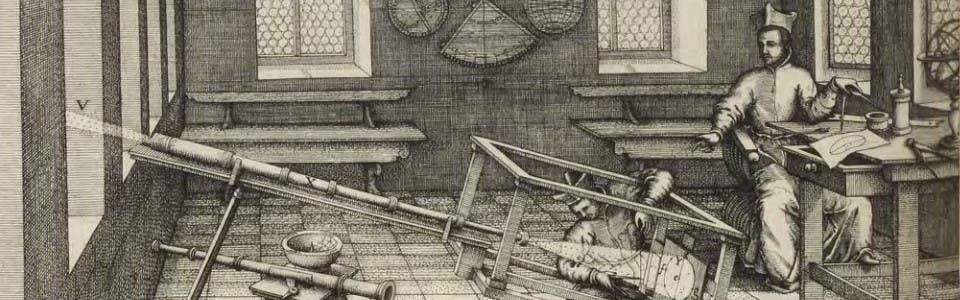

The helioscope repurposed the optical technologies used in the telescope and the camera obscura, allowing for safer and more precise observation of the Sun even during daytime hours when the Sun was at its zenith.

The helioscope worked by projecting an image of the Sun onto a white sheet of paper, a projection method that was first developed by Galileo Galilei’s collaborator, the Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli. Thanks to their collaboration, one of the earliest allusions to the helioscope is found in Galileo’s 1613 work on sunspots, Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari (Letters on Sunspots).

Click here to learn more about Benedetto Castelli.

By 1625, Scheiner had further refined the projection techniques used by Castelli and Galileo into a specialized instrument for solar projection. His model of the helioscope compensated for the Earth’s rotation by placing the instrument on an equatorial mount. Scheiner’s invention of the equatorial mount, which used a rotational axis parallel to the Earth’s own axis of rotation, facilitated more precise tracking of the Sun’s movement.