Scientist of the Day - Thomas White

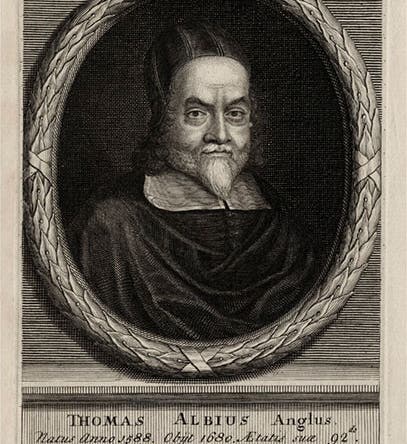

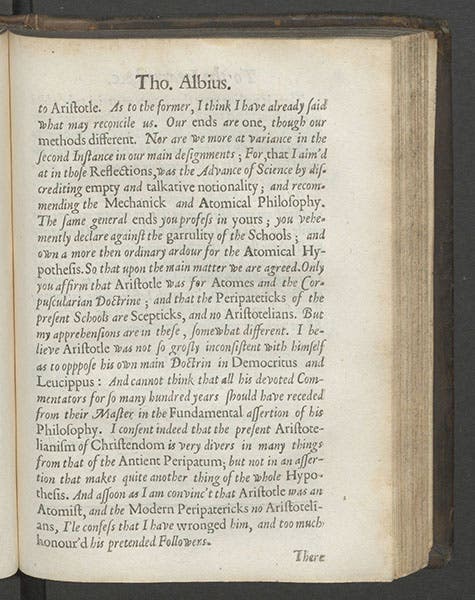

Thomas White, an English priest and natural philosopher, died July 6, 1676, at the age of about 83. White was a Roman Catholic in Anglican England, which meant he had to spend a great deal of his life in exile on the Continent, teaching in various universities and welcomed into the intellectual circle that included Marin Mersenne, René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi, and Thomas Hobbes. White was unusual in that he was an Aristotelian – that is not the unusual part, since most Catholics were Aristotelians – and a proponent of atomism. That was unusual, in the 1640s. There were not a lot of atomists about, but the ones that were, such as Gassendi, generally had rejected Aristotle’s ideas of substance and accidents, qualities and forms, in order to embrace the atomic theory. White held that one could easily incorporate the atomic hypothesis into Aristotle's philosophy, and he did so in his De mundo (1642) and Institutionum peripateticarum (1646), translated as Peripateticall Institutions in 1656 (Aristotelians were often called Peripatetics). White greatly influenced Kenelm Digby, the other notable Catholic English atomist, whose The Nature of Bodies, included in his Two Treatises (1644), was a great influence on later English atomists such as Walter Charleton and Robert Boyle. White also figured in some of the polemics that emerged after the Royal Society of London was founded and critics of the new science soon emerged, in turn calling forth defenders. Joseph Glanvill, a defender, wrote a treatise in 1661 called the Vanity of Dogmatizing, an attack on Aristotelianism, which he called the “Philosophy of the Schools.” White responded with Scire, sive sceptices (1663), defending Aristotelianism and arguing that Aristotle was really an atomist. Glanvill further responded with Scepsis scientifica (1665), which has a long title that ends: "with a reply to the Exceptions of the Learned Thomas Albius," Albius being Latin for White. We wrote a post once about Glanvill, where you can see that title page (and a few others). Here we show a page from Scepsis, headed Thomas Albius, where Glanvill discusses with some respect White’s Aristotelian atomism (second image). The “you” referred to in the text is White. Our copy has been scanned and is available in its entirety in our digital collections.

White also attracted the attention of Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes' first book (written 1643), after disappearing for 330 years, was discovered in the 1970s, still in manuscript form. It was a response to White's De mundo and has now been published. It makes us further realize that Thomas White, whose name is seldom mentioned in surveys of the Scientific Revolution, deserves more credit as a founder of the mechanical philosophy than he has been given. We have White’s De mundo and the Peripateticall Institutions of 1656, in the History of Science Collection, as well as the second edition (1645) of Digby’s Two Treatises. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)