Locks

“The locks, besides being difficult to construct, would also be much more expensive than was anticipated by the Board of Consulting Engineers.” -A.B. Nichols

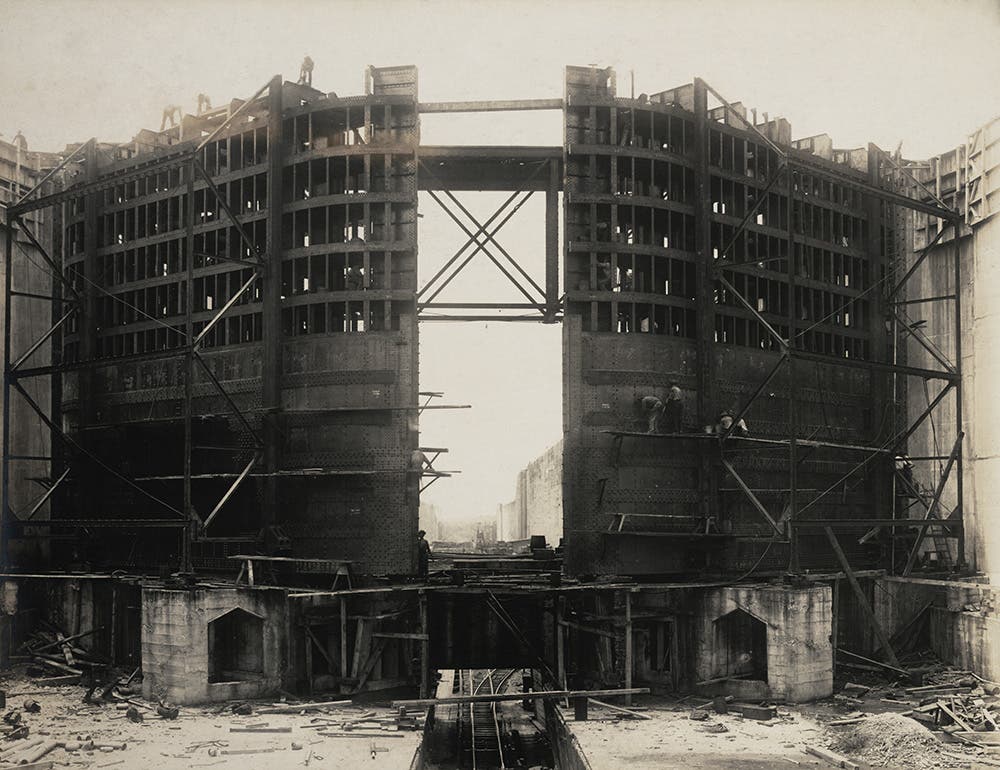

Building a set of lock gates at Gatun. Image source: Nichols, Aurin Bugbee, and Tirzah Lamson Nichols. Panama Canal Collection, 1846-1923 (bulk 1906-1914). Photograph Album 3, p. [29].

Each “leaf” of a pair of steel lock gates is massive. The leaves are 65 feet wide and 7 feet deep, but the height varies from 47 to 82 feet, depending on location. The steel gates are hollow and built as a series of water-tight compartments like a ship, so when the locks are filled, the gates are buoyant.

Whether to build a sea-level canal or a system of locks had not been decided when the U.S. began digging in 1904. Support was strong for a sea-level canal, but it would cost more and take longer than building a locks system. Chief Engineer Stevens weighed in strongly for a locks system after seeing the raging Chagres River in flood. In 1906, by a narrow vote, the Senate agreed.

The plan depended on building a dam at Gatun, on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus, to control the river and create a large lake that would cover much of the Canal route. Gatun Lake, with a surface 85 feet above sea level, submerged close to 164 square miles of jungle. The lake also provided the water to a system of locks to lift ships up from the sea to the lake for the trip through the Canal. Two more sets of locks, at Pedro Miguel and Miraflores, raised and lowered ships on the Pacific side of the Isthmus.

Construction of the Pamana Canal locks involved vast amounts of excavation and the pouring of millions of cubic yards of concrete. Work at the locks began in 1907 with excavation at the lock sites. At Gatun, over 4,500,000 cubic yards of material were removed by blasting and drilling. When construction workers reached the final floor level for the chambers, they removed another 186,000 cubic yards of material by hand. At Pedro Miguel and Miraflores, nearly 4,000,000 cubic yards of material were removed from the lock sites, including 500,000 cubic yards of material that were removed by hand.